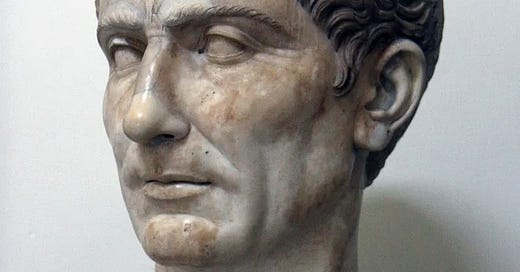

Goldsworthy’s biography covers all of the things that Caesar did, from his political career to his military exploits. It is dense and fascinating, bringing to life a time but also the exceptional career of a leader from the Roman period that first offered a rich assortment of literary sources, along with ample archeological evidence.

First, the institutional context of the Roman Republic. At that time, Rome was experiencing a near-permanent political gridlock. The Republic was in decline, due to the unwieldiness of its procedures and the fatuous intrigues of its Senators and aristocracy. The issues it faced were those of empire and required a steadier hand from a stable executive.

According to Goldsworthy, an excess of institutional access points could be used to block actions, i.e., the aristocratic Senate’s laws could be vetoed by popularly elected Tribunes. Moreover, given that there were 2 consuls (the top executives) serving simultaneously, they had to agree on everything - if they didn’t, one could veto the other. For example, auguries taken by Caesar's co-consul, his mortal enemy Bibilus, were judged "bad" and hence justified him to block any and all political activity. Furthermore, it was individuals and their followers who were important, rather than parties: alliances were largely ephemeral, tending to reflect a function of each politician's pursuit of personal glory rather than a coherent ideology or national concerns. The intricacies of these personalities and institutions are explained with clarity and in vivid stories.

Second, the particular Roman politico-cultural context. After a series of increasingly brutal civil wars, Sulla’s proscriptions (essentially murder or exile and confiscation of all property of political adversaries) had decimated the ruling class in the previous generation, denuding it of high-quality politicians and, perhaps worse, sweeping away the accepted traditions that used to limit their exercise of power (checks and balances via ostracism, etc.). In addition, there was the traditional impetus of family honor, which went back several generations. While honor could serve as a constraint on behavior, it also created an obligation to live up to past glories and offices, sparking nakedly ruthless ambition. Finally, reverence for the republic was akin to a religion, to avoid the autocratic repression of a king. This was similar to American reverence for democracy and the legitimate alternation of power via elected parties.

Third, the unique personality of Caius Julius Caesar. He was an aristocrat from a long-declining family that had lacked honor (attainment of highest office) for nearly a century. From an early age, he had been precocious in astonishing ways. For example, captured by pirates while barely older than a student adolescent, as a hostage he partied with them while jocularly telling them he would return to crucify them and sell their families into slavery. Once ransomed, that is exactly what he did - at enormous personal profit from slave and booty revenues. Nonetheless, as a tribute to Goldsworthy's art as a biographer, we see Caesar as typical of the handful of brilliant aristocrats of his time, just another ambitious youth willing to risk his life to advance. Throughout his entire career, he was one step ahead of utterly ruinous catastrophe. If his innermost thoughts and drives remain a mystery, his pursuit of glory and power was clear. It is as intimate a portrait as possible.

Fourth, the trajectory of Caesar's career. As a struggling politician to the age of 40, with occasional military missions, he built a client base by providing services and cultivating an image as a popularis, i.e., champion of the working class. In this time, we see his friendships with Pompey, Cicero, and many others, in addition to his implacable enemies, such as Cato (a rigid fool, if you ask me) and Bibilus. He also gained an impressive array of lovers, including Sevilia, the mother of Brutus and sister of Cato, which was also a political act.

Caesar was a political genius, rarely making mistakes and always working toward his next exploit, which consistently advanced his prospects. Though born relatively poor, he risked everything with debts incurred to entertain the masses, then found military opportunity to replenish his finances, eventually becoming immensely rich. To run for highest office, he also forewent a triumph, one of the greatest honors possible, which his enemies had denied him through administrative procedure.

Fifth, a microscopic examination of Caesar's military genius. This fills a good half of the book. You get his strategy and tactics, but most interestingly his leadership style. In this respect, Pompey, his great competitor as a general, comes off as an unimaginative engineer of mass confrontation (overwhelming adversaries by superior force and organization), whereas Caesar was a creative underdog, often badly outnumbered, seeking advantage in terrain, tactics, and by understanding the assumptions and strategies behind his adversaries’ behavior.

Regarding his leadership, Caesar cultivated good subordinates, even if for whatever reason they could never equal his fundamental creativity; this required him to make most of the big decisions, of which they were consistently incapable. In this regard, you witness Quintus Tullius (Cicero's brother), Marc Anthony, Labienus, and others. Caesar also respected his adversaries to recognize their own self-interest, which explains his clemency and lack of cruelty, but also his ability to entice enemies to give up without fighting to the death – they could expect mercy.

Sixth, Caesar's egotism. To preserve his dignitas, which his senatorial adversaries threatened via trivial lawsuits in my view, he was prepared to plunge the republic into civil war, resulting in thousands of deaths: rather than humiliation, exile and the end of his career, he used military force - crossed the Rubicon - to smash his adversaries.

Seventh, Caesar’s governance style. Once his adversaries were beaten, he hoped they would cooperate in his projects. Caesar may have been a great reformer, riding roughshod over problems that had festered for decades under the immobile republic. While Goldsworthy continually reminds us of how little we can actually know, he gives a balanced view of what we know Caesar to have stood for. He reduced debts and discouraged the expansion of slavery, rebuilt Carthage and Corinth, enlarged the Senate to include Gauls and other conquered peoples, and granted citizenships to many non-Romans. But he was dead before we could know his fuller vision, if he had any.

Eighth, Caesar’s literary accomplishments. While traveling, he would dictate correspondence, including book-length commentaries that are still studied, to three full-time secretaries - switching from one to the other on different topics while each in turn was occupied with transcribing. In the process, he created both a new art of political propaganda and refined the accepted style of written Latin, challenging Cicero as the premier writer of his time.

Finally, the assassination. Caesar had flouted so many conventions and mortally offended so many, yet allowed most of his adversaries to avoid execution and exile, even allowing some of them to continue their careers. In the last instance, he took one risk too many, in trusting those he pardoned. His complete triumph over them and the absolute power of his dictatorship for life proved too much them to tolerate.

After reading dozens histories of Rome I was astonished to see how much more of a gambler Caesar was than I had imagined. This in my view is the true art of biography: you feel you are seeing a life almost as people did at the time, even if you know what happened in the end. Every single page is fresh and engaging, never bogged down in academic trivia or obscure scholarly proofs, but always sticking to the essence of what we can know and indicating what we can't due to lack of evidence. One of the best biographies I ever read.

Related reviews:

Companion history to HBO's Rome and I, Claudius

When I encounter great historical fiction, I often hope to find a good academic treatment to compare and deepen my perception of them. Holland has strong opinions that he advances with evidence from the ancient sources yet never gets caught up in obscure controversies or proofs. This book covers Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero in conte…

Pivotal turning point of antiquity

This is a narrative panorama of one the great historical watersheds: the slide to the destruction of the Roman Republic. Holland begins with the rivalry of Marius and Sulla. In the late 2nd century BCE, these two generals appeared in the period when Rome was expanding so rapidly that a new source of manpower had to be found: rather than exclusively rely…

Essential to understanding much of Western civilization

Goldsworthy is, I think, the best living writer on Rome. His books, which are at once a pleasure to read as well as at the cutting edge of current scholarship, never disappoint. In this book, he takes on the man who completed what Julius Caesar, his great uncle and adoptive father, might have had in mind (or might not have). When compared to Julius, Aug…

Mr. Crawford, I find your book reviews so informative. Thank you.