Essential to understanding much of Western civilization

Review of Augustus: First Emperor of Rome by Adrian Goldsworthy

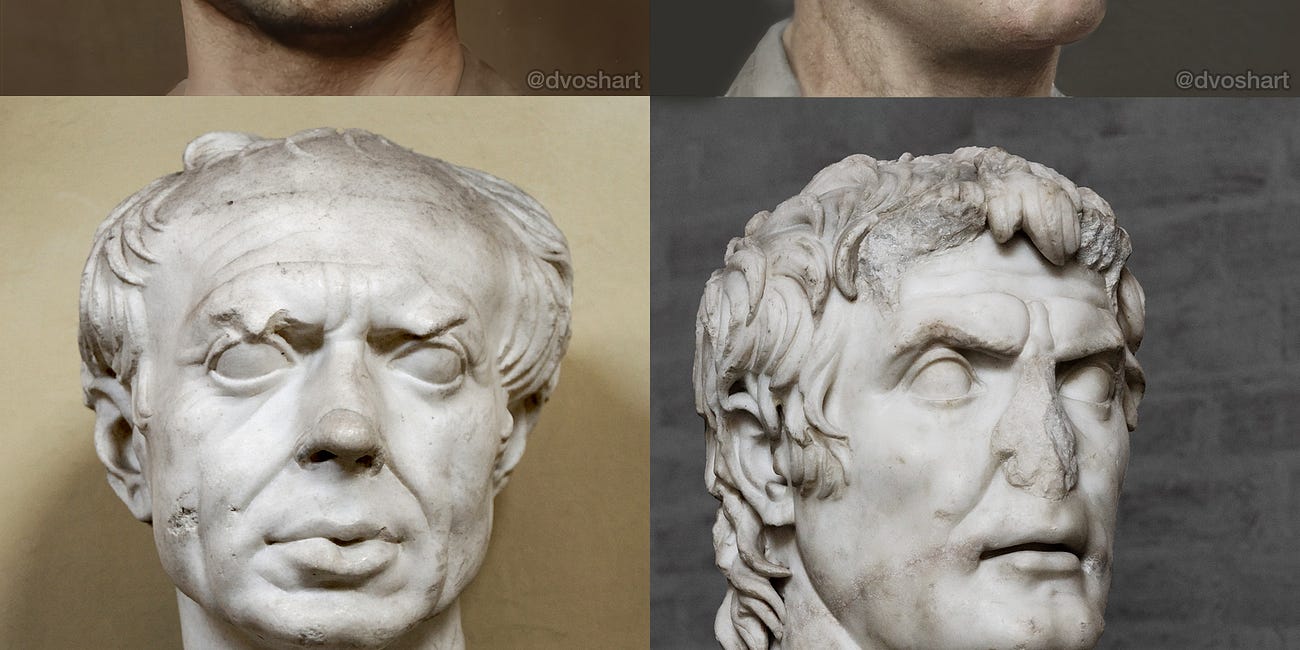

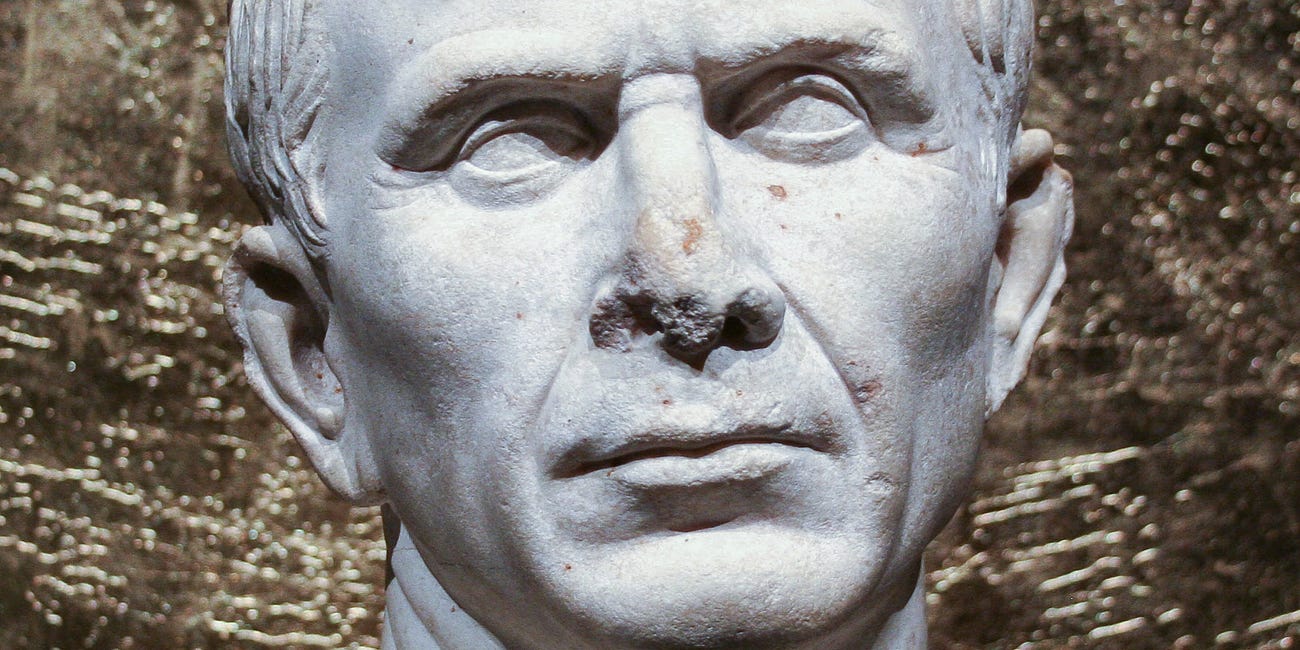

Goldsworthy is, I think, the best living writer on Rome. His books, which are at once a pleasure to read as well as at the cutting edge of current scholarship, never disappoint. In this book, he takes on the man who completed what Julius Caesar, his great uncle and adoptive father, might have had in mind (or might not have). When compared to Julius, Augustus (r. 27 BCE – 14 CE) is far less interesting in appearance: he is cautious rather than bold, not a military man of genius but a delegator, somehow rather bland. Nonetheless, Augustus was a builder of institutions and a molder of society in the very deepest sense, bringing stability after nearly a century of violent upheaval and the author of images of power that would survive as the principal model of government until the 19th century. And, apparently, he died in his bed.

Augustus was born Octavian into an aristocratic family, whose mother was Julius Caesar's niece. Aside from that, there was nothing to particularly distinguish him outside of his own ambition. He was sickly and the times were in terrible ferment: the institutions of the Republic were blocked, with factions able to easily veto the actions of their opponents through multiple channels; with depressing regularity, civil war broke out, decimating the ruling classes of talent. The titan of the era, of course, was Julius Caesar, who beat Pompey, Cato, and many other enemies to achieve dictatorial power. Once assassinated, Cicero and a new generation emerged to reclaim power, including Marc Antony and, at the age of 19, Octavian, who surprised everyone by being named Julius' heir and adopted son in his will (and hence re-named Octavius). After a long struggle, Octavius eliminated all his rivals and reigned unopposed for 40 years. While this is not by any means a boring life, Augustus attracts less scholarly and popular attention than many other figures. This, Goldsworthy proves, is a mistake.

First, Augustus effects an institutional transformation. Goldsworthy argues convincingly that this was not a visionary undertaking, but one of improvisation and expedience. Giving up completely on the fractious power-sharing of the Republic, which had been mired in gridlock since the Gracchi brothers 100 years before, Augustus essentially monopolized power but maintained the appearance of the traditional institutions. He was "first citizen", elected often to the consulship, but preferred to play the powerbroker in the background with others as figureheads under his control.

He became, in effect, a military dictator – with control of the armed forces, which answered directly to him instead of to the Senate. In this way, he could impose order after 50 years of regular, increasingly savage, civil wars, beginning with Sulla. At his death, he had sown the seeds of a monarchy, reversing nearly 500 years of experimentation with a republican form of government that was relatively democratic at times. He may even have believed that these changes had provided for orderly transfers of power, though as we know, this was only partially successful. Nonetheless, Augustus provided the unquestioned model for absolutist government all the way to the Enlightenment. (This is not to say he invented the concept of monarchy, but his was one of the principal examples known in the west.)

Second, he fundamentally altered the political balance in Rome. This was accomplished for the most part by proscription of everyone who opposed Augustus, starting with murder and expropriation in cahoots with Marc Antony, and later in softer versions of exile. The net effect was to wipe out almost entirely the old senatorial aristocracy, leaving more compliant descendants or “new men” in their place.

Third, employing his trusted and brilliant side kick, Agrippa, he mopped up a vast array of military conflicts and internal rebellions. Augustus knew he was not a great general or warrior, so he had the sense to rely on an impeccably loyal subordinate, who did not have his kind of ambition. In the end, the Empire achieved stability over a vast area, almost its maximum historical extent; in accordance with Augustus' policy, it should remain stable and consolidate itself rather than expand.

Fourth, he began a process of professionalization of the administration, installing bureaucrats for longer periods of time than had been possible in the Republic, which sometimes changed administrators every year, when the new consuls took office. Aristocrats and notables still occupied most positions, but there was a new rigor to who was allowed to serve. Heretofore, Rome had governed more as a city state, dominating the periphery with blatant corruption and nepotism. I do not mean to exaggerate – he initiated a process that took centuries to refine and work out.

As the self-styled "father" of the country, Augustus sought to impose a kind of moral order on Rome. Aided by Maecenas, another of his loyal aides, Augustus mastered the use of propaganda for this purpose. Nonetheless, his daughter and adoptive children essentially made a mockery of this persona, in what can only be called a personal and political disaster of epic proportion, resulting brutal, if arbitrary, repression. It was the start of a kind of conservatism that truncated the diversity of morals and literature that characterized the Republic; for example, the exile of Ovid, one of the greatest Latin poets, for both his ironic flouting of morals as a libertine and his liaison with Julia, Augustus’ daughter. While there were many official masterpieces during his reign, some believe that culture and society lost a great deal because of this.

Goldsworthy is conservative in the interpretations that he offers, always sticking to what is irrefutably provable and refusing to speculate on the gossip that advanced such rumors as the murderous nature of Augustus’ wife, Livia, or the rivalries of his heirs. As such, we do not get any confirmation of the colorful personalities and motivations in popular fiction (e.g., I Claudius) or even in certain contemporary sources such as Suetonius. He also refuses in many instances to render judgments on what it all meant. In my view, at its worst this orientation errs on the side of the driest scholarship, making the read less fun and interesting.

I recommend this as an essential source for anyone interested in Rome, in the history of government and imperial institutions, in politics as an art form.

Related reviews:

Fascinating and fundamental interpretation of Augustus' regime

This massive work of scholarship covers the period roughly from Marius to Tiberius, which saw the fall of the traditional oligarchic republic and its replacement by the despotic monarchy as designed by Augustus. While it has a great deal about the politics, it also addresses issues related to the administration of the Empire.

Pivotal turning point of antiquity

This is a narrative panorama of one the great historical watersheds: the slide to the destruction of the Roman Republic. Holland begins with the rivalry of Marius and Sulla. In the late 2nd century BCE, these two generals appeared in the period when Rome was expanding so rapidly that a new source of manpower had to be found: rather than exclusively rely…

Companion history to HBO's Rome and I, Claudius

When I encounter great historical fiction, I often hope to find a good academic treatment to compare and deepen my perception of them. Holland has strong opinions that he advances with evidence from the ancient sources yet never gets caught up in obscure controversies or proofs. This book covers Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero in conte…

Review of Caesar by Adrian Goldsworthy

Goldsworthy’s biography covers all of the things that Caesar did, from his political career to his military exploits. It is dense and fascinating, bringing to life a time but also an exceptional career and life from the Roman period that first offered a rich assortment of literary sources, along with ample archeological evidence.

"at its words this orientation ERRS on the side of ...."