Case studies in Roman military leadership

Review of In the Name of Rome: The Men Who Won the Roman Empire by Adrian Goldsworthy

In this book, Goldsworthy seeks to answer the questions, why did some Roman generals succeed outstandingly and what lessons we can draw? To answer them, he looks at a series of generals from the Punic Wars (3rd century BCE), which ensured Rome's survival and determined its future course, to the last great general, Belisarius, who tried and failed to recapture the western portion of the Empire in the 6th century CE.

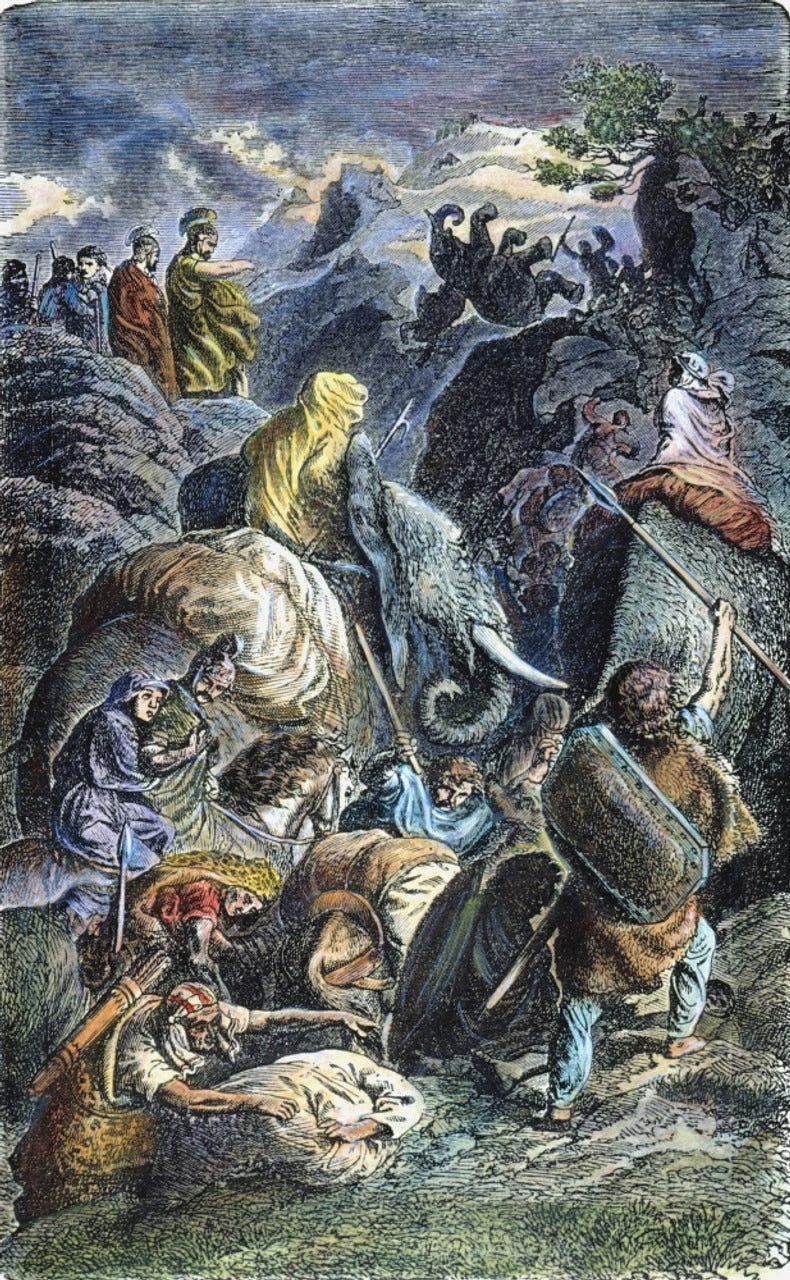

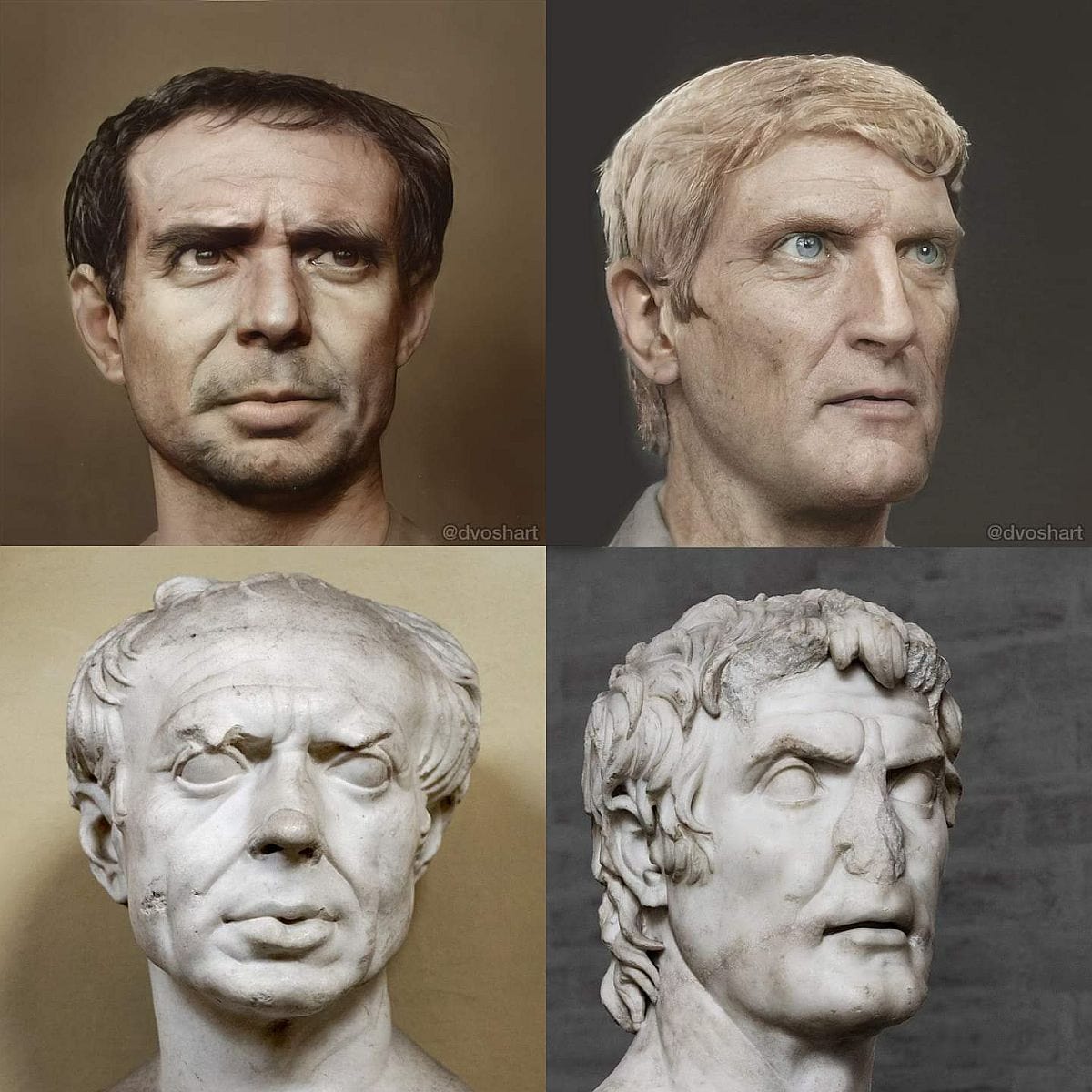

Each chapter offers a detailed portrait of one general, told in a narrative style within the broader context of what was going on, with comparisons to their immediate rivals for power and how well they fit with current circumstances. For example, to counter the seemingly unbeatable Hannibal, Fabius Maximus developed a strategy of delay and avoidance, buying time for Rome to rebuild its forces after a series of catastrophic defeats, thereby taking advantage of his adversary's mistaken assumption that Rome would eventually sue for peace and come to reasonable terms. Though disdained as a dishonorable coward, Fabius enabled Marcellus and later Scipio Africanus to pursue more offensive strategies. In contrast, Julius Caesar fought to enhance his own glory, to become one of the most powerful and famous Romans of all time. These are wonderful studies of character and leadership. That makes it a very different book from Goldsworthy's classic Roman Warfare, which offers neither narrative nor individual portraits, but concentrates instead on more technical detail.

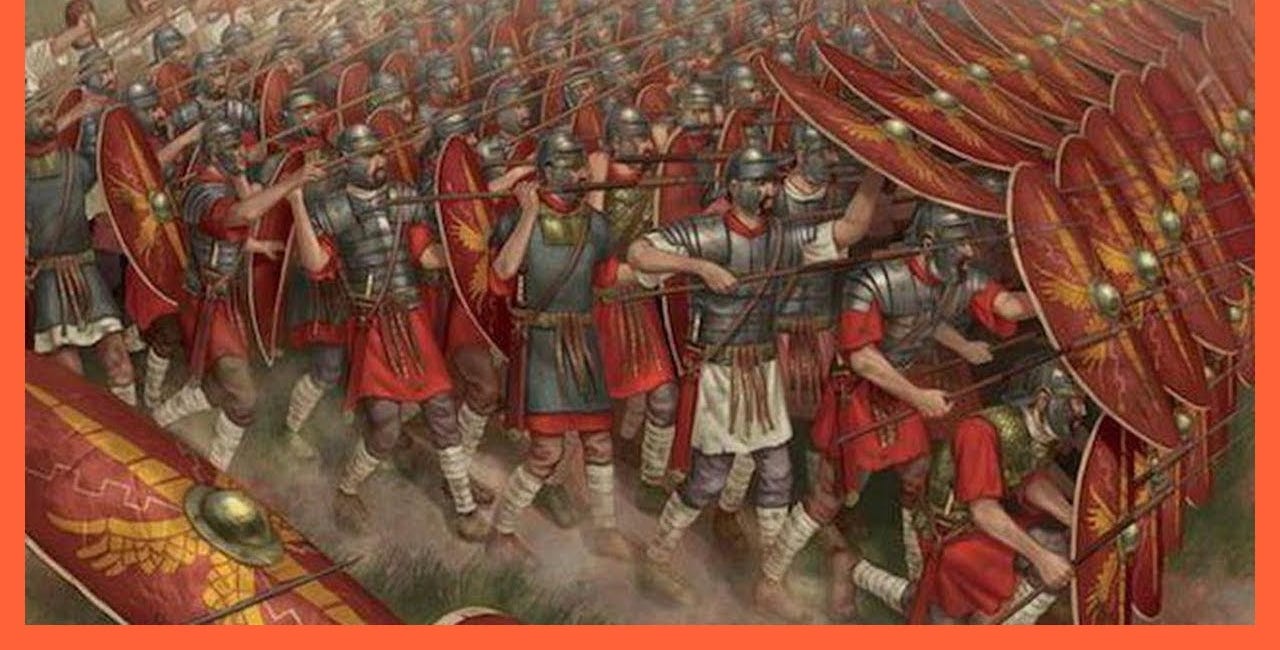

The history of Rome is also brilliantly encapsulated. When its period as Mediterranean superpower began, the greatest threat it faced came from Carthage, a trading empire opposite it on the African coast. At that time, the Roman army was composed of land-owning farmers, clearly amateurs who needed to return for the harvest season or face financial ruin. Once triumphant, Rome turned to mass-territorial conquest, eventually dominating the entire Mediterranean region, this time with a popular army that became a career for the poor and an almost managerial profession for aristocrats. The Roman Empire became more or less stable, a sprawling geographical patchwork that required a very different army to defend it; here, it was composed of smaller forces of different ethnicities and even mercenaries. As countries were absorbed, local aristocrats were allowed to take part as participants and citizens, ensuring their loyalty and widening to base of talent. While it helps if the reader knows this context already, it is not necessary.

The political calculus is also explained in perfect detail. Generals almost always came from the aristocrats, who were born to rule. During the time of the Republic, victory and glory were fundamental to the cultivation of political power: you had to win in order to rule for a limited time at the top of the hierarchy – it was part of the cursus honorum. However, highly competent generals began to be feared as would-be kings or dictators, which led to their mistreatment at the hands of jealous senators.

Though Scipio and others grudgingly retired into obscurity after outstanding careers, perhaps even as temporary dictators in emergencies (e.g., Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus), this later resulted in genuine threats to the political order. As armies became professionalized (a gradual process, Goldsworthy argues), the rank and file became loyal more to their generals than to the Republic itself, which was regarded as quasi-religious but proved politically unable to provide for retired soldiers. With his war on Pompey and the Boni, Julius Caesar definitively ended the honorable retirement tradition, but he had predecessors who waged civil war, i.e. Caius Marius and Sulla.

Following the death of the Republic in 44 BCE, there was a constant tension between the Emperor and his generals: the former needed them to fight effectively, but feared that they would usurp power. Because Generals still came from the largely reconstituted Senate, it remained a hotbed of political intrigue that required constant attention. Often, by acclamation from their men or via their own megalomaniacal ambition (e.g. Constantine), the generals did indeed seize power, particularly when the Empire was so big that generals had to operate in faraway regions for lengthy periods of time. This resulted in dangerous periods of instability, draining resources from defense and soon even maintenance of its vast territories. That is one reason why Rome declined over a long period of time.

Though it is not my principal interest, there is also plenty about military tactics and strategy. The reader can study grand wars of attrition (Gaul), skirmishes that led to negotiated peace or relationships of fealty (Parthia), and sieges (Jerusalem). Throughout, the limitations of the time – slow communications, difficult transport, and muscle-dependent weaponry – offer interesting contrasts with present day technologies. Goldsworthy addresses the relevance of classical studies to the conduct of modern war in his concluding chapter.

Each successful general had a style and faced unique circumstances, Goldsworthy concludes, but shared certain traits, namely, they ensured that their troops were logistically prepared and well trained; they shared the risks but more often maintained distance for purposes of command with an overview; and they instinctively knew where and when to press an engagement. Not all of them were popular with the men, many suffered from distrust and neglect by the politicians they served, and their popularity and glory were fickle at best.

This is a thoroughly engrossing read by a master writer and scholar. Goldsworthy is setting the standard for popular histories of Rome.

Related reviews:

The evolution of the Roman military machine

This book follows the development of the Roman Army from its mythic founding (in 753 BCE) to the collapse of the West in the 5th century CE, over nearly 700 years. The writing is dense and to the point, skipping narrative treatment for hard-nosed analysis. What made the Roman Army unique”? How did it adapt to different circumstances? What was interplay …

The moment when Rome became an Empire

This book is for those seriously interested in the three Punic Wars, the moment when Rome decisively left the Italian peninsula to become a superpower in the Mediterranean. It starts off pretty dry, with a long discussion of the states of Carthage and Rome at the time that the conflict began. While Goldsworthy includes material on their political system…

Rot from within: a grand narrative on institutional and cultural decadence

This book is up to the standard we expect from Goldsworthy: combining up-to-date scholarship with lucid analyses, it also tells a great story. Though this is historical territory that I know well, this is a fresh take that is simply fun to read. Goldsworthy starts with Marcus Aurelius, the last great Emperor of the Roman Empire's golden age. This system,…