Fascinating and fundamental interpretation of Augustus' regime

Review of The Roman Revolution by Ronald Symes

This massive work of scholarship covers the period roughly from Marius to Tiberius, which saw the fall of the traditional oligarchic republic and its replacement by the despotic monarchy as designed by Augustus. While it has a great deal about the politics, it also addresses issues related to the administration of the Empire.

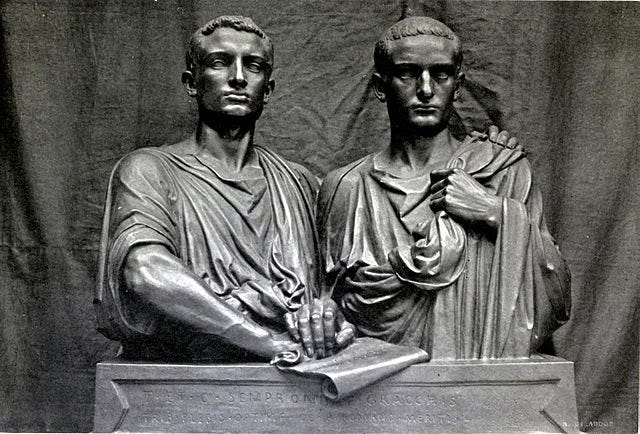

The empowerment of the Tribu…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Crawdaddy’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.