Companion history to HBO's Rome and BBC's I, Claudius

Review of Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar by Tom Holland

When I encounter great historical fiction, I often hope to find a good academic treatment to compare and deepen my perception of them. Holland has strong opinions that he advances with evidence from the ancient sources yet never gets caught up in obscure controversies or proofs. This book covers Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero in context, with evaluations of their careers and legacies. As a Rome history buff, this was a great pleasure to read.

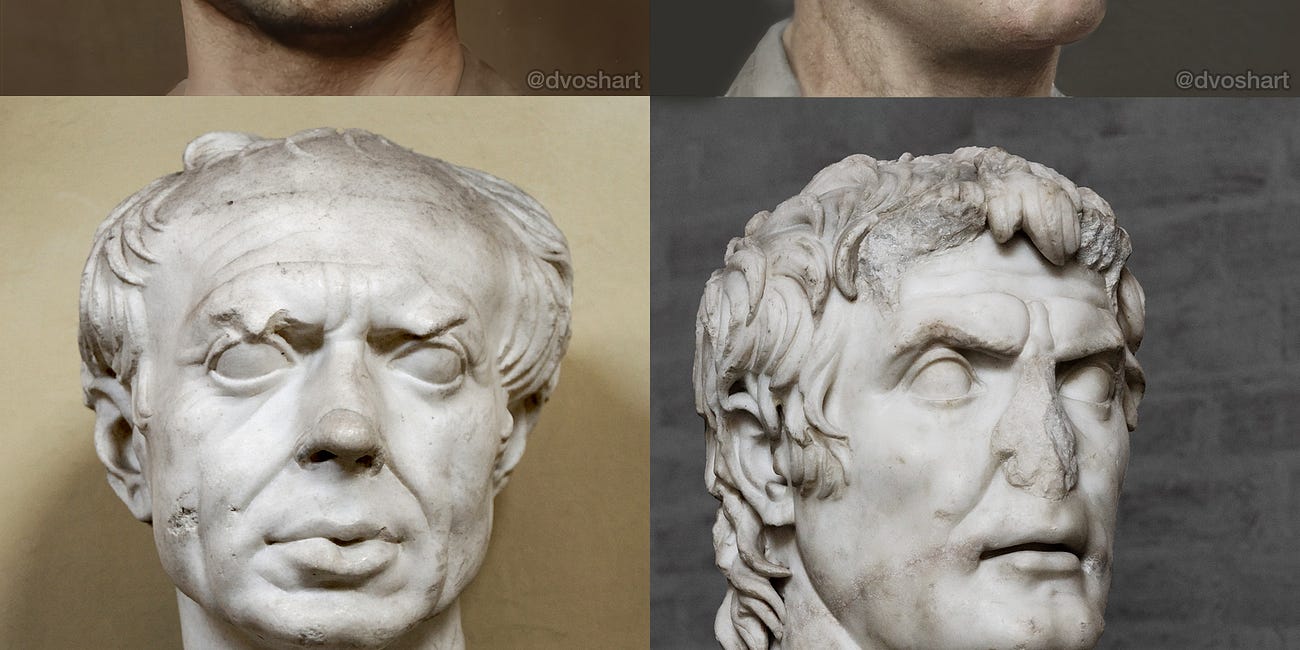

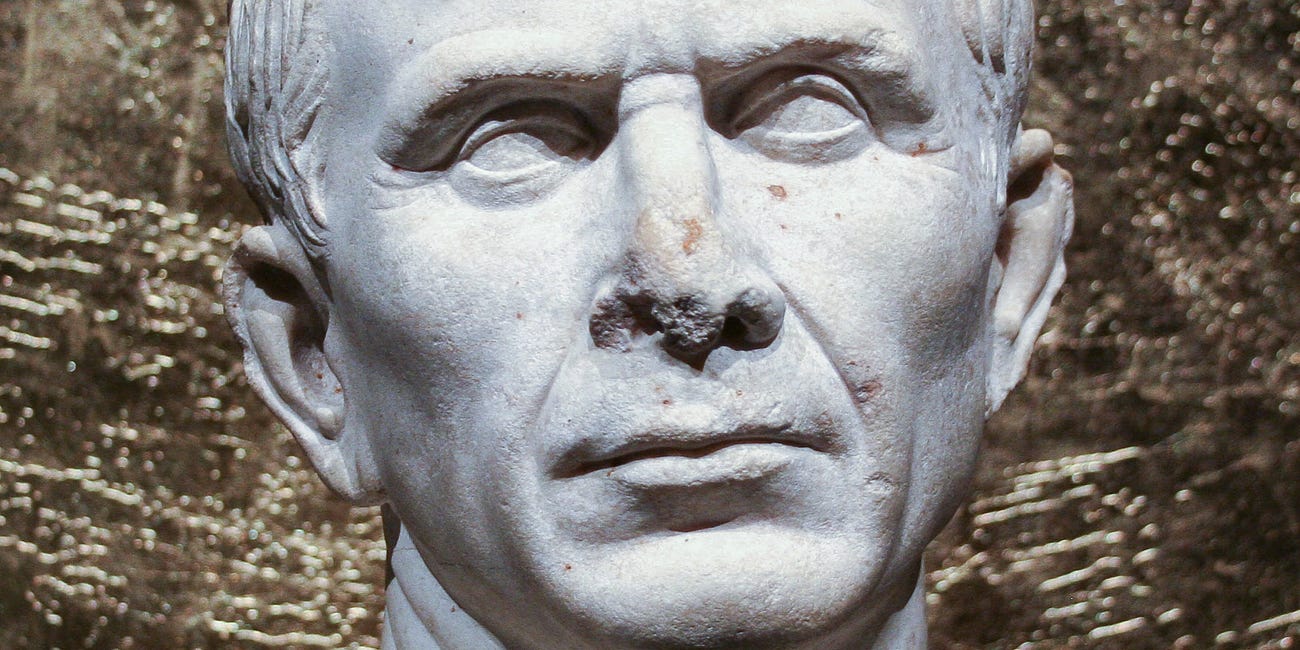

It starts with Octavius, who was Julius Caesar's great nephew and later adopted son. Having observed Caesar's assassination by outraged aristocratic republicans, Octavius was careful to observe the forms of the Republic in piecemeal grants of powers from the Senate, but in reality he was an autocrat supported by military force. His marriage to Livia, whom Holland does not portray as the monster of mini-series (I, Claudius), united the Julian family with the stolid Claudians; it enhanced his legitimacy. In exchange for the maintenance of order and peace on terms that he set – a welcome relief after a century of violent civil conflict and frequent governmental paralysis – Octavius (renamed Augustus) imposed his vision on Roman society, first by proscribing (conveniently rich) enemies and then in wholesale slaughter in a war with Antony.

Augustus' vision was essentially conservative. Rome should return to its ancient virtues of austerity, martial discipline, and family values, minus disorderly things like the Republic. Though avoiding the appearance of a monarchy, he was constantly in search for an heir in his immediate family to whom he could pass power.

To maintain his political ascendance, he created a number of institutional precedents that were to have consequences in later years. First, the Senate gradually lost much of its power, in essence it became a rubber stamp that provided legitimacy to his usurpations. Second, he relied on military force for his real power, in particular the Praetorian Guard, which broke precedent in functioning fully armed within the city limits. Third, with the lengthy tenure of the executive and his dependent appointees, the scope of political maneuver was narrowed to a tiny inner circle of courtiers, such as Agrippa. Fourth, he was viewed as a living god, also adding to his legitimacy and placing the Emperor at the heart of local ritual at the expense of (or competing with) local deities and traditions.

Once Tiberius took over, he tried to follow a mix of the old ways with Augustus' innovations. In Holland's opinion, he was the greatest general of his generation as well as a moderate traditionalist. Unfortunately, as a military man, he lacked Augustus' finesse in management of the Senate and so discounted it further. It was only towards the end of his reign that his hold on power (and perhaps reality) began to slip, especially after he permanently quit Rome for Capri. This enabled the Praetorian Guard to emerge as a major player in increasingly murderous courtier battles, its backing seen as so essential that any heir had to cultivate their loyalty with bribes. It was in Capri that he allowed Caligula to flourish, after having killed or exiled the rest of this family. Once in power, Caligula abandoned the last trappings of the Republic, opening claiming absolute power and Godhead for himself, humiliating the remaining aristocrats for amusement while neglecting the Empire.

Caligula's assassination confirmed the primacy of the Praetorian Guard, which essentially chose to thrust the much-scorned Claudius into power. Because he was relatively competent, it appears, it was during his Principate that the last hope for a restoration of the Republic died. His successor, Nero, was also a creature of the isolated Court, much as Caligula had been without the psychotic excess, though he did murder his mother and many other members of this family. With his assassination, Rome openly emerged as a military autocracy, with the army and Praetorian Guard as the ultimate arbiters of who became Emperor.

Holland wades into many of the controversies surrounding the Emperors. The role of women, for example, is briefly examined. Livia was a dutiful matron, Messalina (Claudius's wife) a power-hungry shrew, and Agrippina (Nero's mum) a savage courtier. The sexual excesses of the Emperors are also discussed, many dismissed as propaganda. I would have wanted much more detail in these areas, but Holland holds back to what can be known.

Unfortunately, the book ends abruptly, without much examination of what followed in terms of institutions and the men that operated them. There wasn't enough analysis for me. This is a narrative history, of course, so perhaps I shouldn't have hoped for more. Tom Holland is one of the best in this genre. A very fun read nonetheless and accurate so far as I can see.

Related reviews:

Fascinating and fundamental interpretation of Augustus' regime

This massive work of scholarship covers the period roughly from Marius to Tiberius, which saw the fall of the traditional oligarchic republic and its replacement by the despotic monarchy as designed by Augustus. While it has a great deal about the politics, it also addresses issues related to the administration of the Empire.

The collision of Rome, Israel, and the early Christians

This is one of those dense history books that separates the true history buff (or academic) from the casual reader. Starting more or less from the reign of the Julio-Claudians – the first imperial dynasty of the Roman Empire after the fall of the Republic – the book compares the cultures when the vassalage of "Judea" (as worked out by Herod during Augus…

Essential to understanding much of Western civilization

Goldsworthy is, I think, the best living writer on Rome. His books, which are at once a pleasure to read as well as at the cutting edge of current scholarship, never disappoint. In this book, he takes on the man who completed what Julius Caesar, his great uncle and adoptive father, might have had in mind (or might not have). When compared to Julius, Aug…

Pivotal turning point of antiquity

This is a narrative panorama of one the great historical watersheds: the slide to the destruction of the Roman Republic. Holland begins with the rivalry of Marius and Sulla. In the late 2nd century BCE, these two generals appeared in the period when Rome was expanding so rapidly that a new source of manpower had to be found: rather than exclusively rely…

Review of Caesar by Adrian Goldsworthy

Goldsworthy’s biography covers all of the things that Caesar did, from his political career to his military exploits. It is dense and fascinating, bringing to life a time but also an exceptional career and life from the Roman period that first offered a rich assortment of literary sources, along with ample archeological evidence.