Weimar's artistic revolution

Review of The Partnership: Brecht, Weill, Three Women, and Germany on the Brink by Pamela Katz

The German Empire collapsed in 1919, ejecting Kaiser Wilhelm II and establishing a tenuous democracy, the Weimar Republic. The entire structure and direction of its society were up for grabs. It was a time of naïve faith in ideologies, as if the political system could create a “new man”. Among other things, this sparked an explosive flowering of artistic expression: not only were the brilliant colors and contorted shapes of Expressionism portraying the inner lives of artists, but the Weimar movement, Die Neue Sachlichkeit, generated radical art that was aimed at reshaping society. Berthold Brecht and Kurt Weill were at the forefront of this experimentation.

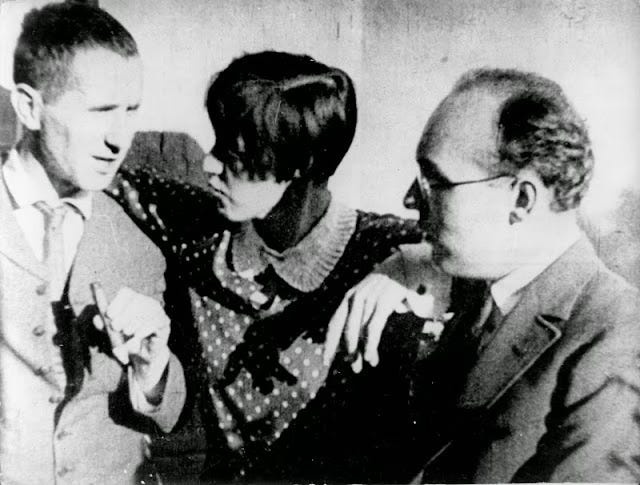

Brecht and Weill developed a seminal partnership in 1920s Berlin. Brecht’s librettos established a new literary vocabulary, bringing art and, supposedly, political ideology to the masses, often through complex and disreputable characters. Sharing his goal of popularization, Weill’s musical scores brought a crucial element of play to their expansion beyond the traditional forms. Together, their gifts reinforced each other, producing some of the most iconic theatre musicals of the 20th century, such as Three Penny Opera. Pamela Katz’s book offers a fascinating exploration of these men and women, their artistic milieux, and of course, the times of the Weimar Republic.

The forms against which Brecht and Weill were rebelling came from a decadent aristocracy, which prided itself on choosing the standards of art with the monarchy, and the rising haute bourgeoisie that largely aped their “tastes”. This symbiosis had resulted in a stilted culture of heroic rhetoric and romantic stereotypes, as exemplified in neo-classical painting and Wagner’s Operas. While the French Impressionists and Austrians’ Secession Movement began to break with these forms in the late 19th century, they persisted in a Prussian-dominated Germany until the collapse of the Empire.

Brecht and Weill sought to occupy a new place in the arts. Reacting against Expressionism (too subjective and myopic) and Dadaism (too nihilistic and absurd), they and other Weimar artists were pioneers of Die Neue Sachlichkeit, the “new objectivity” that attempted portray reality starkly - a twisted and fantastical realism with a radical social conscience. Rather than offer glib certainties or the self-serving answers expected by cultivated elites, they went for popular sensibilities – to bring in the proletariat of growing cities as well as the new avantgarde. To do so, they parodied everything, featuring prostitutes and criminals as protagonists and even heroes. The “truth” was taken to appear in the relation between their work and the audience’s reaction, reflecting Heidegger’s emerging existentialism. In the visual arts, this was the time of George Grosz and Otto Dix. In a way, Brecht and Weill were trying to shape society by leaving the audience with questions rather than answers, to create a state of conflict that would have to be resolved in their minds – after the performance.

Pushing the envelope of the avantgarde, Brecht and Weill entertained the wildest hopes, when art should make a difference, when political man was about to be remade. In retrospect, given the totalitarian regimes that soon came to dominate the era, their views were naïve, perhaps ridiculously so. Nonetheless, this book goes a long way to elucidating what I find so fascinating about the Weimar era. In the chaos, politicians, artists, philosophers, and scientists were pursuing noble dreams.

To round out this vivid portrait, Katz goes deep into artistic biographies of Brecht and Weill and their wives and mistresses. By far the most interesting was Lotte Lenya, whom I remember as the Spectre operative in From Russia with Love. Raised in an impoverished household with an alcoholic father, Lenya was an aspiring Weimar singer and actress when she met Weill; they immediately became artistic and romantic partners for the rest of their lives. Brecht comes off as a classic narcissist, unable to contain his appetites and womanizing. Weill and Lenya had a tumultuous open relationship that perhaps fired their creativity. While the book often goes into way too much detail about their artistic productions, at its best the stories are illuminating and indeed, reinforce Katz’s central thesis on their unique artistic ambition.

As World War II approached, the artists had to flee fascist Germany. At that time, Brecht was attempting to throw out the entire narrative structure of the “hero’s journey” in favor of abstract explanations of society – Hollywood didn’t want any of it. For his part, Weill thrived in the theatre scene in New York, dying relatively young. Lenya wound up living in the Hudson Valley. In his last decades, Brecht wanted to disseminate the Communist ideal and settled in East Germany.

This book is not for everyone, but for those interested in musical theatre, Weimar, and artistic symbiosis, it is a great treat. Katz is also a beautiful writer.

Related:

Kokoschka, Freud and cognitive neuroscience

This book explores two of my oldest fascinations: the birth of depth psychology and the explosion of expressionist art in fin de siècle Vienna. In his brilliant synthesis and update, Kandel includes an introduction to the recent advances of cognitive neuroscience as related to both the perception of modern art and what it says about our brains. I discov…

A conjuncture of factors, then apocalypse

This is a book on the conditions that produced, hardened, then enabled Hitler to flourish, i.e. seize power. Hitler grew up in a remote village of Austria. His authoritarian father, having worked his way into the customs bureaucracy from childhood illegitimacy on an impoverished farm, was proud of his status and wanted his children to follow in his foot…

The birth of Impressionism

This is a magnificent story that pits Ernest Meissonier – the ultimate establishment artist of historical realism – against Edouard Manet, who created a revolutionary style of subjective imagery, offering the “impression” or personal perception of life rather than an exacting replica. At first glance, this might seem like a rather dull subject: we all k…

Political and cultural history of the German mind

As Watson makes clear in his introduction, the principal idea behind this book is that the Holocaust should not completely dominate our perception of German culture, which he sets out to explain and partially redeem. This is a massive intellectual undertaking. Watson explores the flowering of the German mind from 1750 to 1933, including some of its tran…

Wagner as cultural force

Today, Wagnerism is an eccentric cult, a hobby and obsession for that few. In 2005, I seriously prepared to experience the entire Ring cycle at the Lyric Opera of Chicago, both by listening to it first and researching Wagner’s philosophy – he personally knew Nietzsche and read Schopenhauer – in historical context. It was fantastically interesting, but I…

always enjoy your postings. One suggestion: you might want to replace "a fascinating exploration of these men, their women..." with "these men and women" for those of us who believe that men do not "own" or "have" women, and that culture is created by men AND women together. Cheers.