Wagner as cultural force

Review of Wagnerism: Art and Politics in the Shadow of Music by Alex Ross

Today, Wagnerism is an eccentric cult, a hobby and obsession for that few. In 2005, I seriously prepared to experience the entire Ring cycle at the Lyric Opera of Chicago, both by listening to it first and researching Wagner’s philosophy – he personally knew Nietzsche and read Schopenhauer – in historical context. It was fantastically interesting, but I failed to cross the cult threshold. Of course, appreciating his work is one thing, but there is also the baggage: his antisemitism, his posthumous appeal to Nazis, his Teutonic chauvinism.

I have long wanted an in-depth treatment of him and the “Wagnerism” that has influenced western culture so deeply. Ross’ book filled that gap brilliantly. It offers a tour of western history from the appreciation of a rarified intelligentsia in the 19thcentury to its expression in popular culture, from the Hitler panegyric Triumph of the Will to Star Wars.

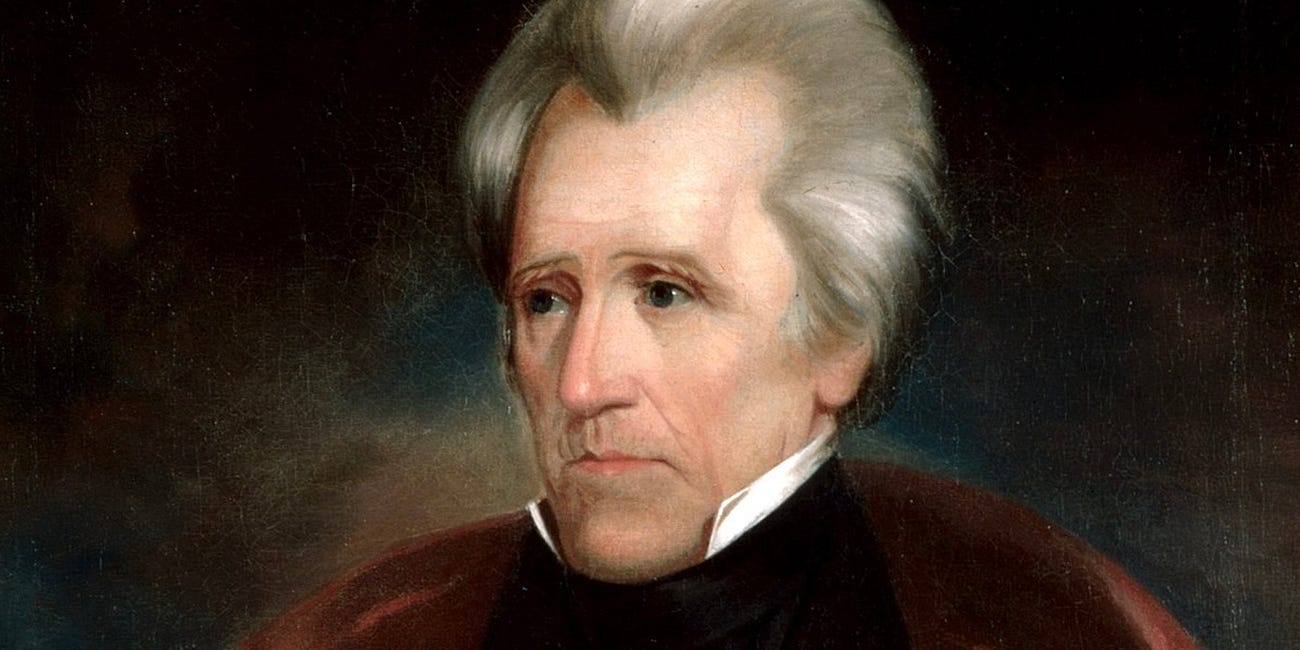

Wagner began his career in tumultuous times. As a radical-democrat participant in the revolution of 1848, he was exiled from Germany for more than a decade. If despotism emerged triumphant in 1849, the command of dynasts was on the defensive, the swan song of more than 1,500 years of “divine legitimacy”. Then, there was science and rationalism, also chipping away at the fragmented Christian denominations in a secularizing age. In addition, industrialization and capitalism were on the ascendent, also undermining the traditional certainties that came with serfdom as cities began to grow explosively. New technologies were enhancing communications and transportation, in effect shrinking the world at an unprecedented rate, while the killing efficiency of new weapons brought fear to entire populations. Taken together, as startling new paths to both freedom and chaos were opening, the old narratives appeared decadent and spent.

Arising from this mess of possibility and danger, Wagner was seeking to create a new mythology, one that would employ art in order to provide meaning - new story lines, and most importantly, a call to action. In this way, he believed the old myths represented the way of parochialism – Wagner wished to transcend the past rather than restore it. His genius, he knew, would provide a new “universal fable”. He would generate a spiritual intensity in the practice of his art, against materialism and Enlightenment rationalism and towards the release of “primal energies”, with an honest acknowledgement of the dark side of humanity, culminating in the exercise of human will against all odds. According to Ross, he set out to save civilization, channeling mythic symbols into artistic and “figurative” values that religions once held as literally true. In this way, the Ring cycle can be viewed as an anti-capitalist allegory, born in revolutionary agitation 1848. Of course, Wagner’s philosophy and politics were shifting steadily rightward from his youthful visions.

In his philosophy, Wagner occupied the nexus of romanticism and modernism. On the one hand, he was rejecting the mechanistic, piecemeal clarities of “science” in favor of mystery and holism. On the other, with a goal to disrupt bourgeois complacency, he was emphasizing his subjective, individual vision. It was art beyond romanticism’s “opulent textures” with their stylized utopian visions and grandiose view of the past, in favor of “hard lines, harsh colors”. In theatrical terms, Wagner was renouncing the “false realism” of neo-classicism in order to transport men to an “ideal realm of unity”, enabling them to transcend a decadent system. His art would recreate life by way of symbol and narrative.

His means to do so was the Gesamtkunstwerk. It sought to unite the music, visual arts, philosophy, and politics in a “comprehensively aestheticized environment” as well as in a holistic presentation. Wagner thought this possible, Ross informs us, because the 19th century intelligentsia focused far more intensively on art than we currently do. Everyone in the know seemed obsessed with Wagner’s artistic works, preoccupying their deepest thoughts and even informing their life choices. His art was supposed to emerge from the opera house and morph into a social model for the future. As Ross puts with his usual elegance: the Wagnerian synthesis represented “Romantic art-religion…bound to Hegel’s dialectic of progress, creating an aesthetic juggernaut”.

Wagner’s myths appealed to imperialists with their presumptions of cultural superiority. It captured the Victorian imagination, a new “secular cathedral space” to contemplate the tensions between an idyllic past and the industrial present. Of course, each country saw Wagner through its own prism. His new mythology could be interpreted as modernist, Arthurian, a return to wilderness, the self-made act of will, etc. The emerging nationalist and socialist ideologies required the invention of mythic past. W.E.B. du Bois saw Afro-Wagnerism as nascent black internationalism, a way to unite the slave diaspora. Women, fighting patriarchy, found their place within Wagner’s universe to think and feel more freely. There was also a large gay subculture that worshipped him.

Beyond his international appeal, Germany remained the focus of Wagner’s efforts. As embodied in his work, conservatives dreamed of something beyond the liberal, bourgeois state, manifesting the “will of the people” (das Volk) in autocratic, militaristic leadership from the top. In retrospect, this was a step toward fascism, with the vaguely defined “glorious, world-conquering spirit” as its calling. According to Ross, Hitler later transmogrified Wagnerism to his purpose. A bit too defensively, Ross emphatically repeats, Wagner did not originate or cause it. (In my view, Wagner did lend fascism momentum.)

Wagner’s antisemitism, as Ross acknowledges, cannot be denied and should not be ignored. He entertained fantasies of vengeance and redemption in a confused and ugly hatred of Jews. They were blame for all modern woes - a global, omnipotent conspiracy that operated in opposition to “the other” (all gentiles). Nonetheless, even Theodore Herzl was an admirer of the self-discovery theme of Wagnerian heroes, in their crusades against entrenched beliefs and forces, their unleashing of primordial emotion, their creation of community art (read: Zionist, nationalist), and their fusion of art and religion.

After World War I, Ross argues that Wagner came to embody how “modernism’s horizon has darkened”, viz the propensity to violence, propaganda as mythmaking, the will to total domination, the feeling that nothing is stable in our ever-changing modern life. Thus, Wagnerism “summons Schopenhauer’s Will”: unconscious, pathological, subhuman forces. Karl Jung saw him as a “master of comparative mythology”, while Joseph Campbell called him an “initiator of modern myth creation”. The Gesamtkunstwerk is as fecund as it ever was, if less in fashion.

A great deal of the book is devoted to an examination of Wagnerism’s impact on Modernist art. In the most hifalutin terms, Wagnerian modernists opposed prevailing norms, introducing transgressive themes, “threatening zones of bourgeois comfort” (I love Ross’ use of language), smashing the conventions of imagined utopias, releasing primitive unconscious energies. Gesamtkunstwerk fed directly into stream of consciousness, e.g. Virginia Wolff rejected the pretty portrayals of the “fabric of things” of contemporary British novels in order to “capture the inner life of her characters” in all their subjectivity. Even as Dada and futurism opposed Wagnerian culture, Ross asserts, they “worked from a Wagnerian script”.

In more popular and populist veins, Wagnerian imagery continues to dominate film, political propaganda, and innumerable other art forms. There would have been no Tolkien without Wagner, Ross asserts, indeed perhaps no fantasy genre in literature. While this strikes me as stretching the concept a bit too far, Ross provides a number of striking examples, from Hitler’s posters of himself in Teutonic armor to the grand hallway in the Star Wars award ceremony, Volume 4, and the helicopter Valkyries in Apocalypse Now.

This book is a wonderful tour of the last 170 years of culture as spawned by an artistic genius. Because it is a somewhat difficult text and not an introduction, I think it might be better for those steeped in these issues or for Wagner aficionados. I thoroughly enjoyed it.

Related:

The mother of all turning points, even if it didn’t quite turn

I have long sought a detailed account of 1848: it was a time of myriad movements, crises, hopes, violent revolutions, and even more brutal counter-revolutions. As a moment of such utter complexity and import, it is key to understanding the tensions of the present day. While this uneven book dwells too much on the details of the violence and political ma…

The philosophy behind Romanticism

This is a splendidly dense introduction to the Romantic Movement. Isaiah Berlin argues that the Romantics established a new kind of relativism and possibility, forever demolishing the 2000-year search for absolute certainty in philosophy.

World Kulturgeschichte at a crucial moment of transition

I have long been fascinated with the 19th Century, during which the modern world emerged. According to Paul Johnson, the period 1815-1830 established the necessary conditions: in relative peace and political stability, the growth of the capitalist economy, and a confluence of new ideas, in particular “the Demos”. While his book is predominantly descript…

A seminal reading experience, mixing art criticism with history and biography

Since my high school infatuation with surrealism, I have been fascinated with every aspect of modernism. What caused such an explosion of experiment and rebellion? What, if anything, did the various disciplines have in common? What linked Monet and Picasso to Ravel, Hemingway, Frank Lloyd Wright, and even Sigmund Freud? Somehow, it seemed all of a piece…