Kokoschka, Freud and cognitive neuroscience

Review of The Age of Insight: The Quest to Understand the Unconscious in Art, Mind, and Brain, from Vienna 1900 to the Present by Eric Kandel

This book explores two of my oldest fascinations: the birth of depth psychology and the explosion of expressionist art in fin de siècle Vienna. In his brilliant synthesis and update, Kandel includes an introduction to the recent advances of cognitive neuroscience as related to both the perception of modern art and what it says about our brains. I discovered all of these things in college in the mid-1970s and was astonished at how the fields had changed and in a sense, come closer.

Given the number of disciplines involved, the book goes in many directions. It starts with the historical context of 1900 Vienna, a cosmopolitan capital that was more or less welcoming to all the nationalities and religious groups. Though a major city, the intelligentsia was surprisingly close knit, even across fields. There were major salons where Freud could have met novelists and artists such as Robert Musil and Gustave Klimt. According to Kandel, their works and interests were convergent.

Psychoanalysis focused on the unconscious as a major factor in mental health, which was also an aspect of the brain. Freud was, Kandel says, applying the scientific methodology under development at University of Vienna: observe, hypothesize, verify, but this time to heal psychic wounds. As difficult as it is to imagine now, he was part of the movement to bring medicine into the hard sciences, though Kandel notes that many of Freud's ideas were intuitive speculation and limited by current knowledge and his own inexperience, in particular his misunderstanding of women’s sexuality.

Viennese artists were exploring the notion of the unconscious in their own way. On the one hand, pushing into new directions because photography had rendered realistic painting redundant, Klimt and then his acolytes Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka were experimenting with the portrayal and evocation of strong emotions, essentially inventing the mature form of Expressionism. Following the lead of Van Gogh and Munch, this involved the merging of Mannerism and caricature, with grotesque poses, strong colors, and flat backgrounds of color or design. (Kandel focuses a great deal on Kokoschka, who of the three never appealed to me personally, making a convincing case for his pioneering genius in terms of empathetic art in which the viewer is included as a participant.) On the other hand, local writers were experimenting with narrative, bringing the viewer in to participate in their fiction, much as the painters were doing.

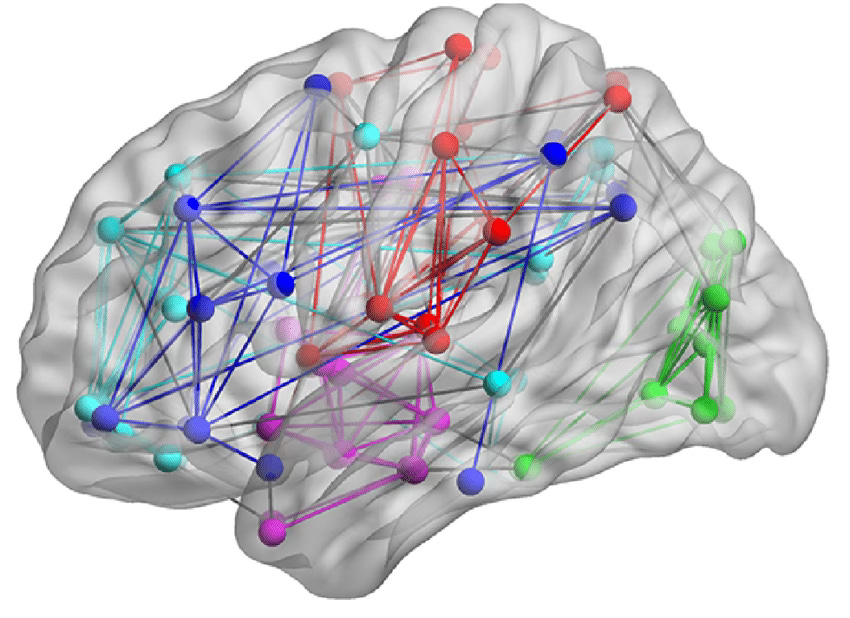

Finally, Kandel covers related developments in cognitive neuroscience. The perspective is both historical and scientific. While this was the most difficult section for me, it was in many senses the most rewarding. Developing directly from Freud and his search for unconscious brain function, Kandel takes the reader through gestalt psychology, that is, the ability of the brain to quickly construct an understanding or image of the whole from a limited number of characteristics, as recognized in discreet aspects such as a straight line, color contrast, and ovals of the face. Once imaging techniques were perfected (PET and CAT scans from the late 1970s), detailed neurological maps could be constructed of how brains function in real time. This was a revolution in science that occurred after the elementary studies in psychology that I pursued in college. For example, consciousness is at least partially explained by a large number of areas in the brain acting in concert. Kandel also shows how the old Freudian model – of ego, superego, id, etc. – are actually located in a functional, dynamic map of the brain; I had no idea such a thing was possible. As Kandel demonstrates, Freud and the artists earlier in the century were tapping directly into these discoveries, if in inchoate form.

The book is not an easy read, but it helps if the reader is acquainted with the artists of the time, modern depth psychology, and the examination of the brain as a biological organ. It is at the high undergraduate level. The best thing about the book is that Kandel succeeds in tying it all together and calling for more research in neuro-aesthetics. I cannot do justice to the subtlety and erudition of his arguments, but was spell bound throughout the entire book. Furthermore, I can't say that I have a full grasp of cognitive neuroscience, but it enhanced my appreciation for the art of the time and partially explains why all it began in Vienna in 1900. Finally, Kandel recognizes the contribution of Freud and clearly explains the deficiencies of psychoanalysis without going overboard as many critics do. However, I remain uncertain that I completely grasp why Vienna was the place at that time for these discoveries.

Related:

Freud, Klimt, Herzl, and Schönerer

I got the book to get an idea of why it was in Vienna that the extraordinary flowering of the ideas that defined much of the 20th century came to fruition. It was an era of fundamental reinvention, similar to the Renaissance. It offers a good description of the evolution of these ideas, as embodied in architecture, the rise of nationalist demagogues, ar…

From enlightened despotism and bureaucratic centralism to uneven democritization and nationalism

Judson's aim in this book is to prove that the myriad ethno-linguistic nationalities of the Habsburg Empire did not inevitably pull it apart. This goes against the conventional wisdom. He makes a good case that the monarchy provided a focus to local aspirations as they opposed parochial aristocrats' domination of the local economy and public affairs, a …

The unbelievably intricate path to catastrophe

The title, The Sleepwalkers, says it all. I have never understood why the great powers of Europe went to war in 1914 and after reading this, it is clear that they did not know either. This book is about how it happened, in a huge narrative on all the contributing players, from the tubercular assassin of Archduke Ferdinand to the ineffectual Tsar in Russ…