The United States in formation

Review of American Republics: A Continental History of the United States, 1783-1850 Book by Alan Taylor

This is a delightful narrative on that period in US history where the country was massively expanding, defining itself, and dividing into the hardened blocks – regional and ideological – that we can still see today. Taylor begins his book at the moment that the Federalists imploded and the Republicans, as led by Jefferson, emerged as the new dominant party.

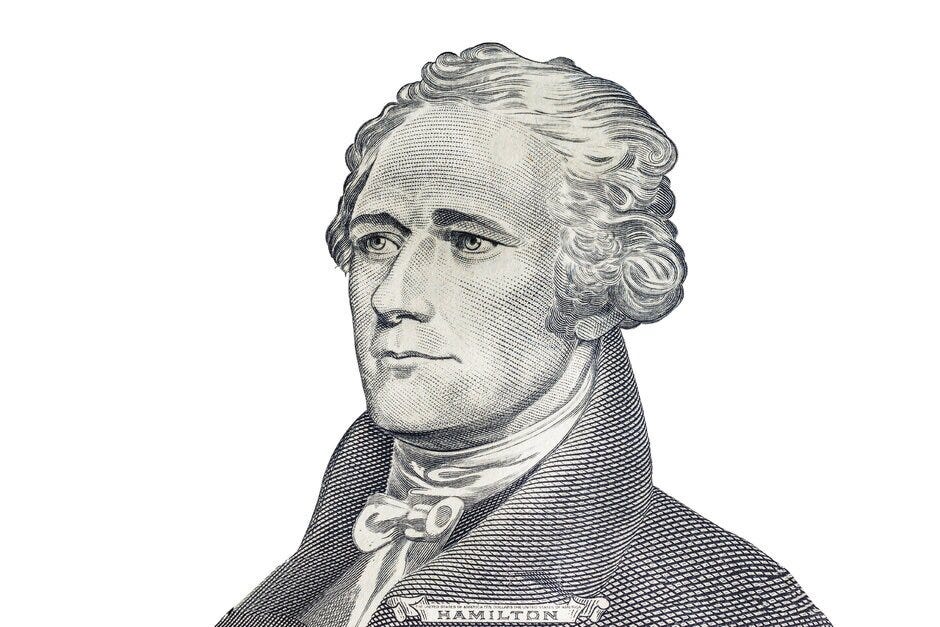

The Federalists had included virtually all of the founding fathers, with the exceptions of Jefferson and later, Madison. The Federalists believed that a strong executive was needed to provide direction and coherence to policy and governance, in such areas as taxes, commerce, tariffs, and industry. George Washington was the leader of this group, with Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton as his mercurial righthand man. With John Marshall as the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, the Federalists were able to achieve certain judgments that would define how the vaguely written Constitution should be interpreted, coming out clearly in favor of a strong executive and Federal power over the states in certain areas. Perhaps the most emblematic of the Federalist policies was the establishment of the first Bank of the United States, which was supposed to regulate the banking industry as well as issue paper currency, collect taxes, and finance government activities. It gave crucial support to the nascent manufacturing base.

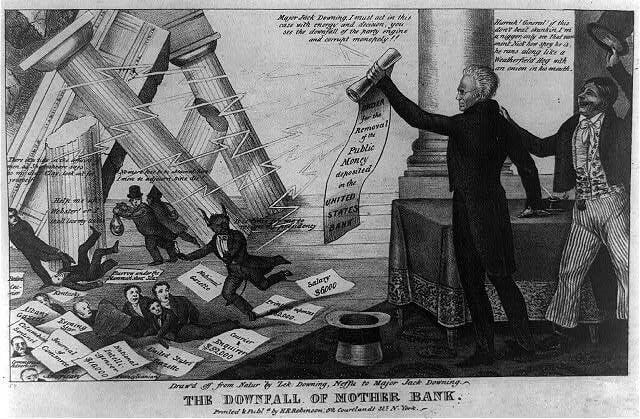

Opponents of the first Bank of the United States worried that over-centralization of power in the financial system would interfere with the market and, most importantly, enable political subterfuge and corrupt officials in the Treasury Department to enrich themselves. (Hamilton was called “a young Napoleon”.) This was one of the most contentious issues of the early Republic, particularly in light of the panic of 1820.1 If this was one of the focal points of their political movement, Republicans also opposed urbanization and industrialization, which they argued would undermine the yeoman farmers of the heartland, the supposed bedrock of the Republic. The future, they argued, lay in expansion into the western part of the North American continent.

For a variety of reasons, the Federalist Party imploded. Some of it was executive overreach, some of it the rarified manner in which they ran their politics (via patronage and a kind of pseudo-aristocratic presumption in their right to govern). To them, active campaigning was “vulgar”. In a nutshell, they succumbed to popular, proto-democratic impulses. In contrast to the rational, technocratic paternalism of Washington and Hamilton, these new forces reflected not the Enlightenment Federalists but the Romantic movement – popular, passionate, religious, irrational, a darker view of human nature. Once the Federalists lost their monopolies on political and economic power, they never recovered. It was time for a new political coalition, the Democratic-Republican Party, which of course fell immediately to infighting, united only briefly to carry out the War of 1812.

Once Jefferson took over, there was no looking back. He cut back on the Federal Government’s scope of activity and took steps to realize his dream of westward expansion, sending Lewis and Clark to gather information about the journey to California and Oregon. The Louisiana purchase, which doubled the size of the US, was only the beginning: subsequent presidents took huge territories from Mexico (roughly Texas, New Mexico, and California), negotiated with the British for territories in the northwest, and pushed into uncharted Indian territories. This doubled the size of the US once again and opened an entire continent to development by 1850. Needless to say, this was an era of genocide and the crudest of grabs for wealth imaginable. The Native American populations were repeatedly devastated. Taylor covers this is vivid detail, ignoring none of the sad, lurid details. That’s not woke, it’s what happened.

Slavery was another of the issues that festered during the period. As the basis for the southern economy and lifestyle, it was becoming the greatest threat that the Union had yet faced. The issue became particularly acute with the geographical expansion: if new states were banned from slavery, the reasoning went, the political balance would shift in favor of the northern states, which Southerners feared would enable them to abolish slavery and destroy their way of life. Taylor covers the ins and outs of this controversy in great personal detail, making it come alive better than any account I have read so far. The best that the political system could do was attempt to strike a balance, so that neither side could control the other. It was bound to fail – eventually. Developments in the world (revolution in Haiti, the abolishment of slavery in England, for example) boded extremely ill for the south, which instilled fear into their politicians.

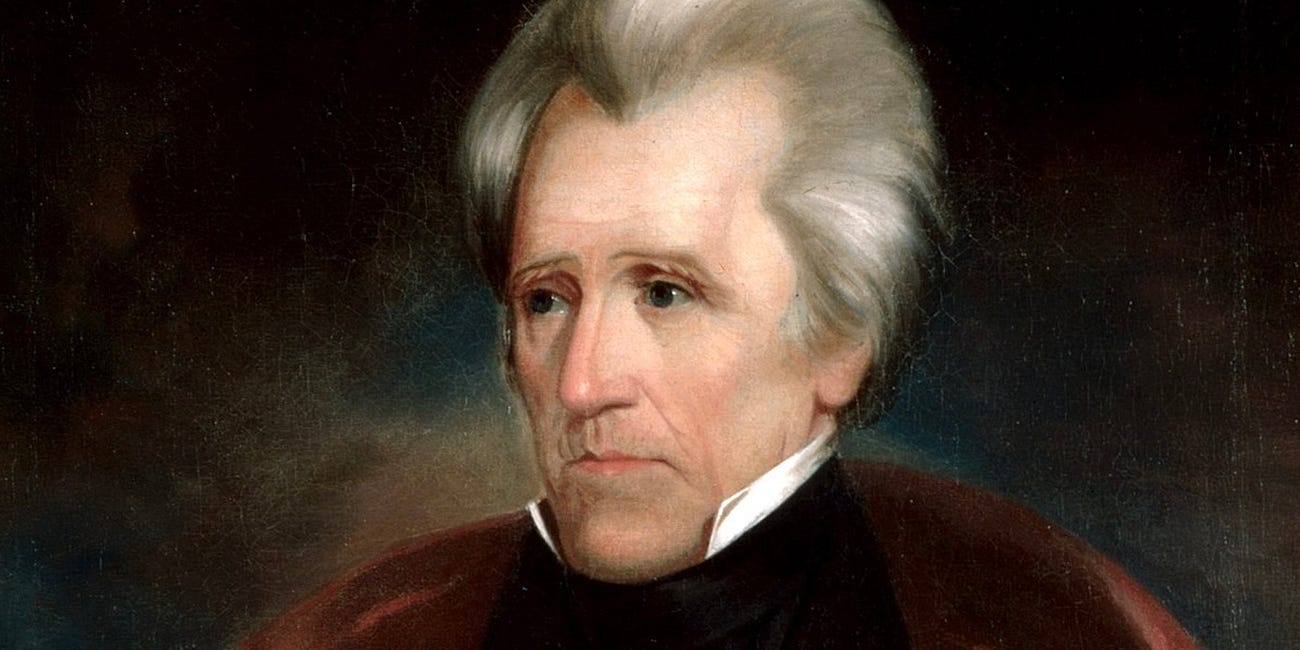

During this period, with the exception of the chaotic confederation that immediately followed the revolution, there was a steady deterioration in leadership quality. Washington and Jefferson were without doubt political geniuses, dominating their eras and resetting the terms of operation. For all his faults and brutality, Jackson was the last strong president. He led the genocidal despoliation of Amer-Indian lands, ejecting them into ill-defined western territories when he didn’t kill them outright and refusing them and former slaves their rights of citizenship. On the other hand, Jackson vastly expanded the electoral franchise, a key enabling factor in the movement from elitist Republic to popular democracy, while curtailing the role of the Federal Government (in particular ending the mandate of the Bank of the United States, sowing monetary chaos in the process). The presidents that followed him were indecisive and pathetically impotent in heading off the coming crisis over slavery, but they did continue the expansion westward.

This was also a period of massive religious conversion, the Second Great Awakening, a counterpoint to the democratization of the political system. Evangelical preachers assured white supremacists in the south that their cause was just, indeed mandated by God, while others argued precisely the opposite to abolitionists in the north. This absolutist, exclusionary reasoning was a major contributing factor in the buildup to the Civil War. Many of the sects we know today, such as the Seventh Day Adventists and the Mormons, emerged then.

The mentality of the time was crude at best. Codes of honor could still provoke duels, not just between Hamilton and Burr, but by Southerners feeling abused by any kind of criticism of the institution of slavery. Blacks were almost universally viewed as inherently inferior, even inhuman, and unable to manage their own affairs, let alone participate as citizens enjoying constitutional rights. The Amer-Indians fared little better, their sophisticated cultures remained poorly understood and they were disenfranchised and murdered in their turn. The details of their treatment need no recapitulation here.

The book ends with the country on the verge of violent dissolution. Regional quasi-wars were breaking out between pro-slavers and abolitionists in Missouri, Kansas and nearby territories. Debate in Congress was stalled and increasingly violent. With the 3/5 vote rule, the south continued to wield disproportionate power, in particular through the Democratic Party. The Whigs, who had split off from the Democratic-Republican Party, fell progressively into disarray, too weak to oppose the Democrats. Leaders appeared helpless to stop the disintegration of the polity, let alone attempt to resolve the utterly incompatible sides being taken. At this time, the world continued to look on the US with contempt and skepticism, not just at the dysfunction of its institutions, but in the lack of refined culture. Europeans assumed that the United States would soon break up.

The great virtue of this book is the vividness of its narrative character. Even though I knew many of the facts, I gained a feeling for what transpired.

Related:

Visionary, revolutionary, courtier, and protean bureaucrat

Hamilton is one of those extraordinary achievers you find every few decades in politics. He had the energy and drive of Lyndon Johnson and the scholarly credentials and writing ability of Thomas Jefferson. To be sure, it was luck that placed him in the thick of a revolution that created a new form of government, but he got himself there without privileg…

The movement celebrating darkness, individuality, and wholeness

From the moment that Rousseau rebelled against the Enlightenment – with its assurances that everything could be known and arbitrated by reason – a new and unruly movement emerged. The Romantics would challenge what we can know, how we should study the world and ourselves, and questioned even the precepts of happiness and the "good life". As Blanning pro…

World Kulturgeschichte at a crucial moment of transition

I have long been fascinated with the 19th Century, during which the modern world emerged. According to Paul Johnson, the period 1815-1830 established the necessary conditions: in relative peace and political stability, the growth of the capitalist economy, and a confluence of new ideas, in particular “the Demos”. While his book is predominantly descript…

Romanticism in America

The Transcendentalists’ principal concern was the power of the individual human mind (and spirit) to shape both personal life and the world. This stood in sharp contrast to the Enlightenment and in particular the Empiricists, such as John Locke, who emphasized facts, external circumstances, and objective science as the prime movers of change. The “inner…

Holding collateral rights, the Bank of the United States came into possession of properties sold off during the panic, only to sell them at huge profits once prices recovered in the following year. This galvanized opposition.