World Kulturgeschichte at a crucial moment of transition

Review of The Birth of the Modern: World Society 1815-1830 by Paul Johnson

I have long been fascinated with the 19th Century, during which the modern world emerged. According to Paul Johnson, the period 1815-1830 established the necessary conditions: in relative peace and political stability, the growth of the capitalist economy, and a confluence of new ideas, in particular “the Demos”. While his book is predominantly descriptive, he offers the perspective of a traditional Tory, which is both interesting and extremely annoying.

With the conclusion of the War of 1812 between the US and Great Britain, the greatest economic and naval powers agreed to pursue a mutually beneficial relationship, based on trade rather than geopolitical competition. In settling their territorial disputes and though Canada remained in the British orbit, its border with the United States became the longest demilitarized border in the world. This allowed them, Johnson argues, to invest capital in productive enterprises, sparking the early industrial revolution. Of course, Johnson does not go deeply into the sources of said capital, which predominantly came from the slave trade and slave-based plantations. It is an omission typical of the book. Britain also took on the role of the “world’s policeman”.

In a similar development, via the cleanup diplomacy following Napoleon’s devastating wars, the Congress of Vienna (1814-15) set up a balance-of-power peace in Europe that would last more or less intact until World War I – an entire century! This was unprecedented since at least the pax romana, if ever. Designed to perpetuate the old regime, the Congress attempted to install monarchical regimes throughout Europe, which Johnson observes was ultimately futile: in the continuing reverberations from the French Revolution as well as the explosive growth of an urban proletariat, the push for more representative government and institutions was gathering steam. Characteristically, Johnson’s take is somewhat skeptical: democratization “was not inevitable…[n]or was it necessarily progress” (p. 904). As a good Tory, Johnson seems to prefer the monarchy to the democratic rabble – even now, he says, it is too early to judge.

Regarding the technologies in development – what the capitalists and their governments were investing in – the greatest improvements came in transportation. As train tracks were being laid and sea transport rapidly improving, the world seemed to shrink – human expansion into all spaces led to the decimation of indigenous peoples. If many feared that humankind was pushing the limits of nature, that our resources may prove finite, a belief in eternal and unambiguous progress dominated the worldview of many of the elites.

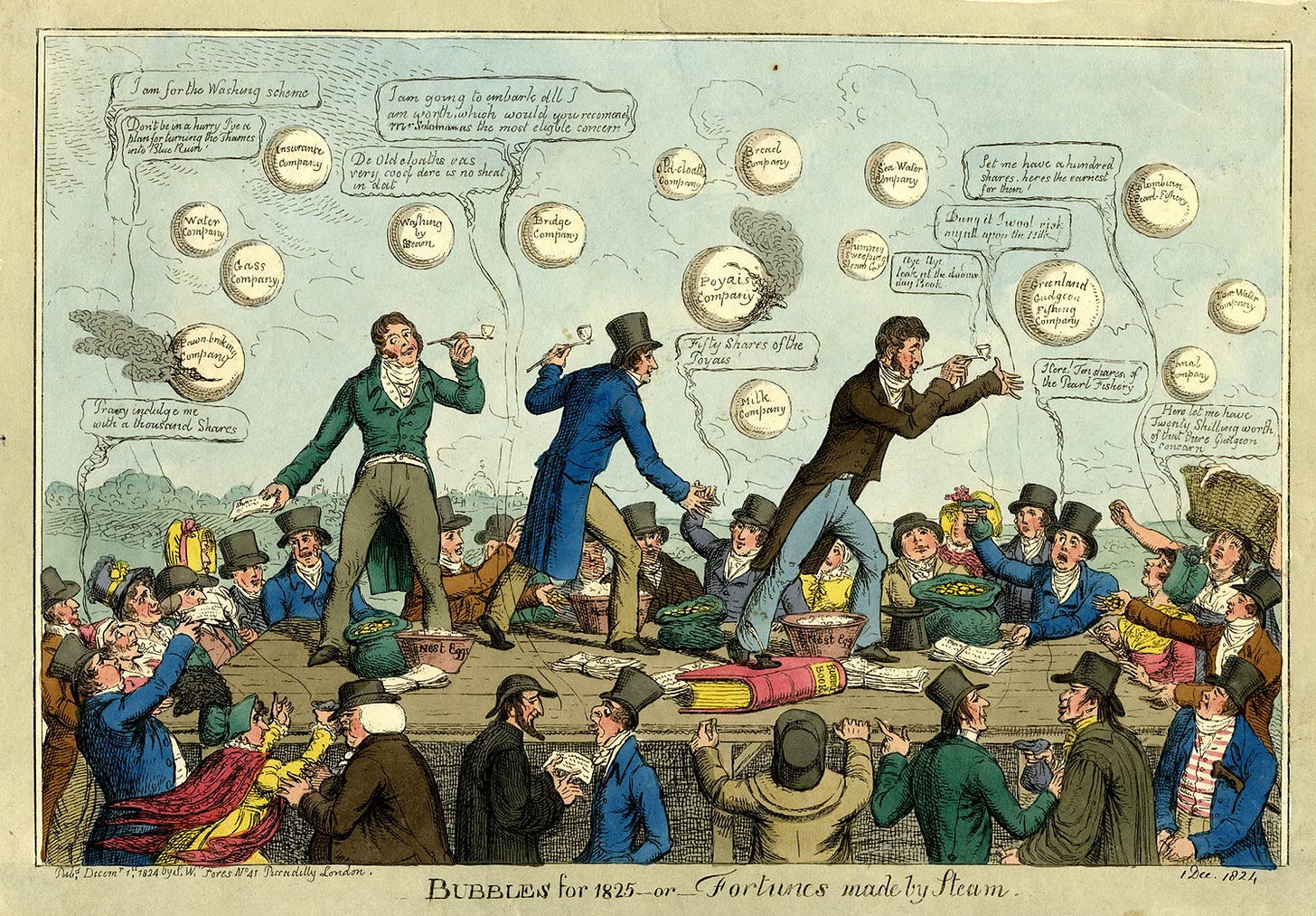

The chapters on economic development during the period were particularly interesting to me, a retired business writer. With the appearance of organized capital – huge and innumerable banks that were managed to a degree by governments – speculation began to run in cycles that were completely unprecedented in their magnitude and impact. From 1815, an investment boom began to gather steam, offering what seemed like an unstoppable momentum. In both the US and UK, government guarantees of banks, controlling their liquidity, encouraged lending in real estate, industrial undertakings, and enterprises such as mining.

However, by 1820, there was a serious financial panic in the US. The particular institutional arrangement in force had huge political impact. Acting as guarantor for regional and state banks, the Bank of the United States (BUS) had obtained collateral: it in effect owned the real estate, which it had purchased at deflated prices from those unable to pay. As the recovery began the next year, BUS was able to sell these collateral holdings at enormous profit, which of course outraged those impacted, which was virtually everyone. This accelerated the disillusionment with the Federalists (who had advocated that landed, “responsible”, “interested” elites should rule the rabble) as well as their opponents, the Democratic-Republicans.

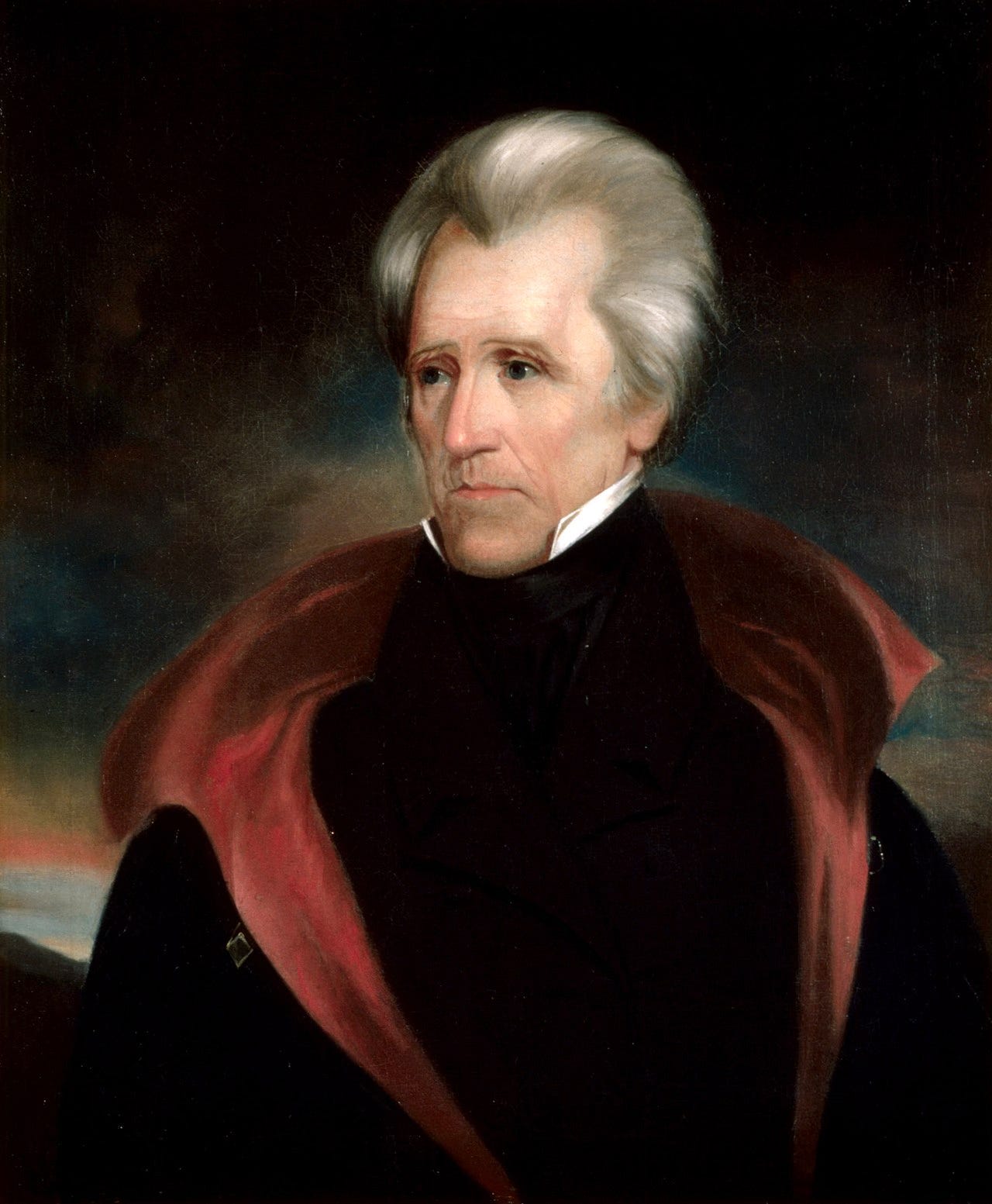

The politician who gave voice to their discontent was Andrew Jackson, a hero of the War of 1812. Jackson called for a widening of the electorate, in effect a populist democratization, and a dismantling of the Federal Government, starting with the BUS. He served as President from 1829 to1837. Beyond his populist agenda, he aggressively pursued a policy to depopulate the eastern US of native American tribes, in effect pushing them westward, into reservations, or simply annihilating them.

In the meantime, huge changes were roiling societies everywhere on the globe. One of the most important phenomena was urbanization. With industrial employment opportunities and an increasing organization of the workforce, cities were growing explosively. Unprecedented concentrations of people naturally led to political unrest, particularly in view of the new uncertainties they were facing, i.e. bust-fueled unemployment and poverty, introduction to views that contradicted their rural religious backgrounds, and a desire for enhanced representation. Industry was extremely primitive, conditions often brutal, and the social safety net at that point non-existent. Clearly, the monarchies set up by the Congress of Vienna would have to adapt, which many of them strove to do with varying degrees of success. In the less developed world, about which Johnson can barely contain his disdain, the upheavals were even more violent and eventually, authoritarian. He devotes a lot of space to the revolutions in Latin America, which for whatever reason he portrays as bloodthirsty and ineluctably backward.

Johnson covers many aspects of world society. In western fashion, trousers replaced aristocratic breeches in revolutionary France; this reflected the rise of the working classes and citoyen, but also shifted attention away from the male physique (cod pieces and muscled thighs, that is, the style as one sees in portrayals of say, Henry VIII) almost exclusively to female display. Perhaps most consequential, scientific careers were beginning to become possible in organized settings and international communities, opening the door to professional talent rather than the aristocratic amateurism of the 18th Century. In my opinion, Johnson gets into a bit of trouble with his enthusiasm for the scientific Zeitgeist: he asserts, for example, that Immanuel Kant and poets such as Coleridge “foreshadowed electromagnetic theory”, which is nonsense. Finally, Johnson rightfully notes that a new skepticism represented a rebellion against the presumptuous arrogance of Enlightenment philosophes, who believed that science would lead to unending progress and riches.

Many of these developments again stalled in the financial panic of 1825, which was the first genuinely global depression of the modern age. Having quickly recovered from the 1821 bust with government aid, banks had over-leveraged themselves in questionable ventures and speculation, in particular in the new world, reaping enormous paper profits. Once undertakings in Latin America proved unprofitable and real estate and other speculative bubbles reached their maximum, the banks attempted to call in their loans, causing a contraction from which it would require many decades to recover. Revealing the fragility of the new capitalist prosperity, this knocked the classical economists off their perch, reinforcing the skepticism against hyper-rationalist precepts. What is clear is that much was unknown about the workings capitalism, the government of that time was unable to cope with the complexity, and the lower classes were abandoned to their own devices.

In the context of the depression, Johnson makes one of his more glaring rhetorical slipups, revealing his stuffy Tory prejudices with a whiff of antisemitism. He describes early 18th-Century financial machinations as “the traditional Jewish skill of transferring bullion and specie securely”. His tone is so brazen and unapologetic that the reader cannot but conclude that he was of an earlier generation.

In spite of my many criticisms of Johnson’s approach and attitudes, this is a stimulating read. The book is predominantly about Britain and the USA – after all, they were on the vanguard of the changes underway – but it attempts to provide a Kulturgeschichte of the entire world in a crucial moment of transition. Johnson intended it for educated audiences, who would be able to discern his message in the plethora of detail. There is not a boring page in the book. I see many things more clearly and feel I must delve deeper into my research on the 19th Century.

On a technical note, the book is exactly 1,000 pages and clocks at 4 pounds. For compulsive types like me, I was easily able to calculate the percentage of the book I’d read to a decimal point. There are no illustrations and the footnotes run to only 71 pages, rather than the 300 or so you’d find in a textbook.

Related:

Sociology of 19th century history

History books tend to move between narrative and analysis, or put simply, a story vs. an interpretation of the forces and trends behind events. The narrative stresses the role and impact of individuals, while the analysis looks to abstractions, factors, and ideals. Osterhammel’s book skews as far to the analytic side as may be possible, in a sense it is…

The emergence of modernity

This trilogy covers Europe from the French Revolution to the eve of World War I, the watershed developments that shape the modern world - the establishment of constitutional democracy, industrialization, secularization, scientific discovery, and radical artistic experimentation, to name just a few. It is a splendid introduction. The approach is not narr…

The philosophy behind Romanticism

This is a splendidly dense introduction to the Romantic Movement. Isaiah Berlin argues that the Romantics established a new kind of relativism and possibility, forever demolishing the 2000-year search for absolute certainty in philosophy.

How Enlightenment philosophy developed and was applied in the real world

Gay’s ambition with these two books is to describe the Enlightenment mindset and assess how the philosophes’ ideas worked out in the real world. What was new and different about them? How did they change our approach to science, psychology, society, then political science and government? What was their practical impact? If you want answers to these ques…