The start of the Belle Époque

Review of Rites of Peace: The Fall of Napoleon and the Congress of Vienna by Adam Zamoyski

The defeat of Napoleon left Europe in disarray. To establish a new order and stable peace, representatives from all great European powers - Great Britain, Russia, Austria, and Prussia - convened a multi-lateral diplomatic body. Bourbon France also attended.

The conventional view of the Congress of Vienna is that Metternich established a system to balance the great European powers off of one another, achieving a relative peace for decades. At least, that is the argument that Henry Kissinger made and which, he claimed, he was trying to recreate under Presidents Nixon and Ford. While this is a fascinating concept, I have always wondered if such a system had existed, let alone whether it was possible. In Adam Zamoyski’s extraordinarily vivid and incisive book, I believe, he convincingly demolishes Kissinger’s thesis and proves it is wishful nonsense.

The Napoleonic Wars left a devastated Europe. Not only did it exhaust the human and material resources of the states involved, but Napoleon had imposed an autocratic version of the French Revolution on them, weakening traditional institutions, redrawing the maps of vast territories, and delegitimizing many of its leaders. In the Congress of Vienna (1814-15), the victorious powers formed a diplomatic alliance that sought to resolve the issues in one fell swoop. To put it mildly, the process was a mess, the allies became increasingly alienated to the brink of war, and their vision looked to the absolutist past rather than to a future in which the voice of the people counted. In other words, they wanted to reimpose the Ancien Régime, a futile ambition given the rise of the bourgeoisie, industrialization, and the ongoing democratization of many institutions, all of which undermined the decadent power base of the aristocracy.

Beyond the petty appeals for compensation by disenfranchised aristocrats who had lost virtually everything under Napoleon, there were a few major issues that the players wanted to resolve.

Given the reconfiguration of many territories – Prussia lost a significant portion of its possessions in Poland to Russia, for example – the victors felt they had to be compensated by the addition of new lands at the expense of enemies or other, weaker allies. Prussia was to get a portion of the Saxon Kingdom.

The calculus for this compensation was how many “souls” (i.e. native populations) they would gain, a resource for the state as they rebuilt their armies. While there was some discussion regarding the quality of the lands and the educational levels of their peoples, it came down to brute numerical calculation in the end.

In addition, the losing states often had to officially recognize, hence accept, their shrinkage. For example, the king of Denmark had to give Norway to Sweden in compensation for Russia having taken Finland; he was humiliated and disenfranchised.

Finally, Germany was a chaotic agglomeration of quasi-states, having been reduced to about 30 from over 200 pre-Napoleonic sovereignties, many of them petty. The question was whether to meld them into a functioning federation or not. (It was of course left to Bismarck to consolidate Germany into a single state 6 decades later.) Interestingly, France was not punished at first.

It was a lot to handle. Not only were the strategic interests of the allies in play – Austria was worried about the resurrection of Prussia at its expense – but the rulers themselves often had idealistic ambitions, however quirky or personal they may have been.

Tsar Alexander I of Russia saw himself first as the savior of Europe and liberator of Poland, taking on a messianic role as a mission directly from God; while claiming an enlightened spirit, he also wanted to protect Russia from disruptive western ideas, wandering increasingly into mystical meditation with an obscure prophet. The other diplomats wished to preserve the prestige of their rulers as well as their nations, restoring absolutist systems and national security. The British were also keen to abolish the slave trade, if not slavery itself.

For their part, the French were recognized as an equal power due to the efforts of Talleyrand, in the service of the restored King, Louis XVIII. Louis had proven so politically inept that Napoleon had easily been able to claim the loyalty of the military once he escaped from Elba. Upon Napoleon’s defeat in 1815, France suffered extensive losses of territory. Moreover, the balance of military powers was based on antiquated notions of how war was evolving, rendering it irrelevant from the get-go.

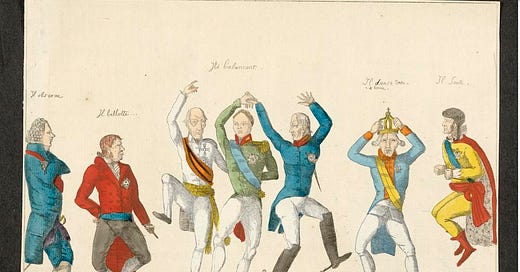

Though more or less a diplomatic history that covers negotiations and proposals extensively, Zamoyski delivers a wonderfully rich tableau on the ongoing pomp and shenanigans, particularly when they had bearings on outcomes. For example, Metternich was seriously distracted by a love affair with princess Wilhelmina, whom Alexander may have blackmailed because he had custody of her love child in Russia. Nearly everyone, it seems, was sleeping around, switching partners, and joining in on elaborate entertainments to the point of physical exhaustion. It is a fitting view into the death throes of the Ancien Régime. Having been isolated for so long, British diplomats and their wives were scorned as pathetically behind the times in terms of fashion. It would be funny if so much had not been at stake.

In addition, the decline and fall of Napoleon is covered at length in the first third of the book, perhaps to excessive detail. It wasn’t what I read the book for, but it did set out the complexity of what the diplomats faced. Among other things, Napoleon proved that a new era of warfare and diplomacy was dawning, one in which the voice of the people was gaining in importance, the rules of war were changing, and technology was about to make a quantum leap in lethality and logistical capabilities. Decisions would no longer be based on the whim of absolutist rulers, but would require cooperative solutions in multi-national coalitions, especially to transnational issues such as slavery and anti-Semitism. The diplomats understood virtually none of this. Even the concept of a “balance of military powers” was based on antiquated notions of how war was evolving, rendering it irrelevant from the get-go.

This is a very interesting narrative on a major turning point in history. I thoroughly enjoyed the writing and the details. If I would have liked a bit more explanation of the forces that were rumbling underneath, Zamoyski offers an excellent sumup at the conclusion.

Related:

The emergence of modernity

This trilogy covers Europe from the French Revolution to the eve of World War I, the watershed developments that shape the modern world - the establishment of constitutional democracy, industrialization, secularization, scientific discovery, and radical artistic experimentation, to name just a few. It is a splendid introduction. The approach is not narr…

World Kulturgeschichte at a crucial moment of transition

I have long been fascinated with the 19th Century, during which the modern world emerged. According to Paul Johnson, the period 1815-1830 established the necessary conditions: in relative peace and political stability, the growth of the capitalist economy, and a confluence of new ideas, in particular “the Demos”. While his book is predominantly descript…

Radical, yes, but only a step on the way

If the title is a blatant provocation – “failed” is a more marketable title than “partially succeeded” – this is a rich intellectual history. It argues that the “radical” Enlightenment philosophes played a key role in the late 18th century revolutions, losing out to the conservative reaction of the next century. The book is beautifully written, places i…

Democracy consolidation in historical context

There are plenty of books about what makes democracy work. What's new in this book is that it looks at democracy as an evolutionary phenomenon with a view to uncovering the factors that portend success or failure. Rather than a static view, Berman argues that we must look at the

The high Belle Époque

This book is about the cultural currents of the late Belle Époque, the generation just prior to World War I. Rather than treat it as a decadent precursor to the war, that “fateful, spiritual Ennui” that is popular convention, Tuchman strives to portray how the people of the time saw themselves, what they were thinking, and what they were trying to do. T…