The high Belle Époque

Review of The Proud Tower: A Portrait of the World Before the War, 1890-1914 by Barbara Tuchman

This book is about the cultural currents of the late Belle Époque, the generation just prior to World War I. Rather than treat it as a decadent precursor to the war, that “fateful, spiritual Ennui” that is popular convention, Tuchman strives to portray how the people of the time saw themselves, what they were thinking, and what they were trying to do. The result is an absolutely first-rate narrative history full of outsized personalities and ambitions. In it, the reader can explore what Lloyd George, anarchists, Richard Strauss, Freud, Rosa Luxemburg, and the Impressionists and Expressionists had in common.

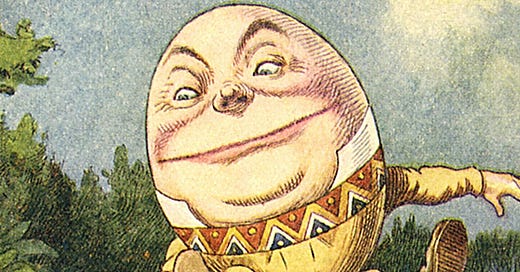

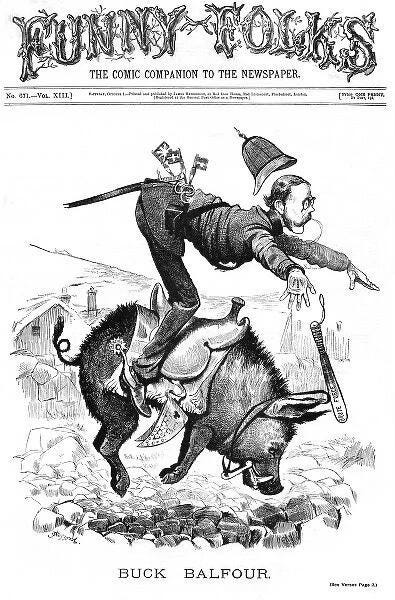

The chapters are organized around grand themes. First, there is the patrician regime and culture in the UK. The landed elites expected, and were expected, to govern the lower classes. Tuchman covers their education, culture and belief systems. For example, Balfour (Eton-Cambridge) was an aristocrat whose Godfather was Duke Wellington. He was dashingly handsome, considered himself a philosopher, and stultifyingly conservative. Needless to say, he left a mark on his times, not only in the Balfour Declaration but in expanding education; he opposed home rule for Ireland; he was even parodied in Alice in Wonderland (as Humpty Dumpty). It is a wonderful and funny portrait among many of a class that was struggling to survive the forces that industrialization and democratization were releasing.

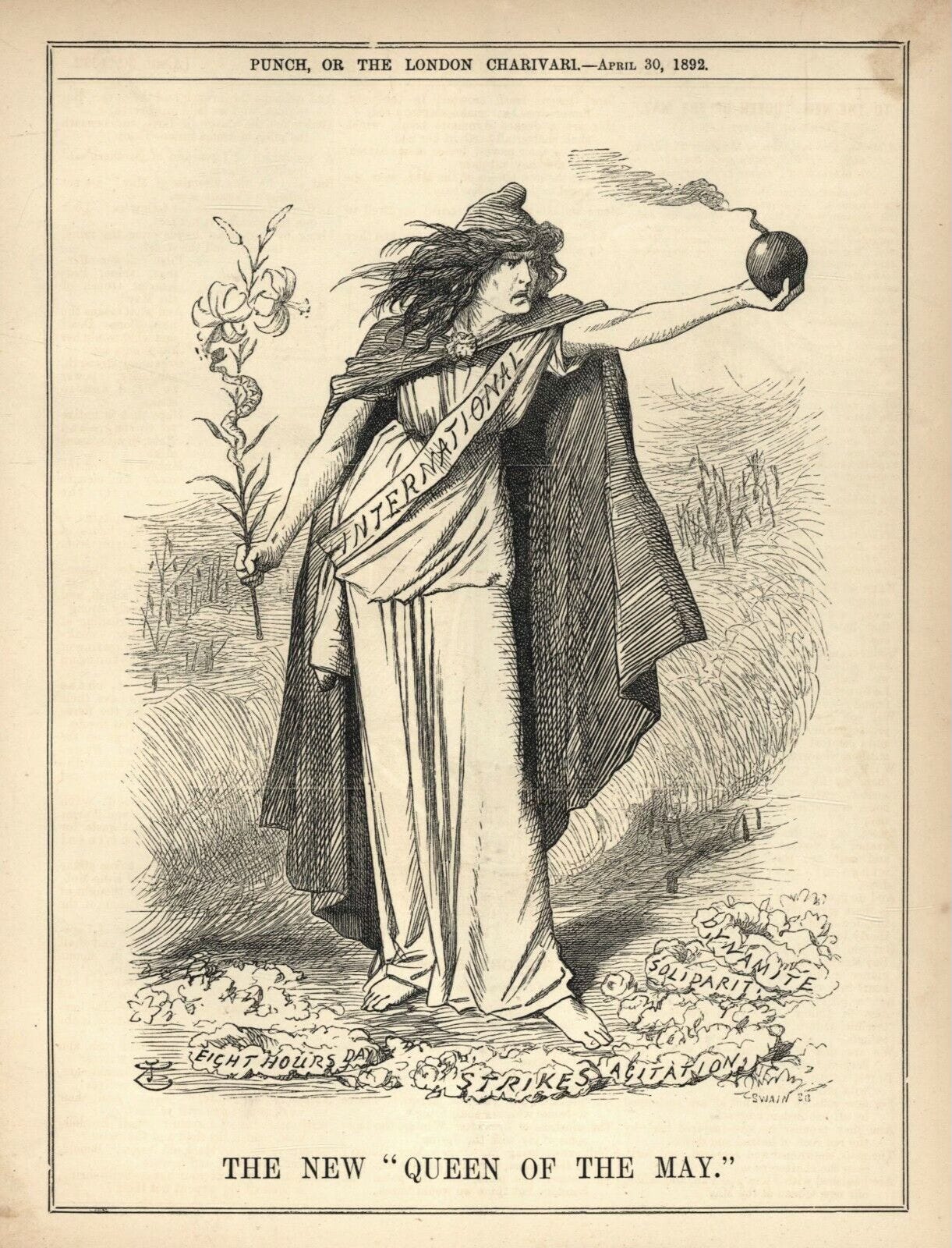

Second, there was the anarchist movement. These were radical opponents of the state who eschewed any organization whatsoever, preferring to act as plotters and assassins in order to inspire the underclasses to collectively bring the order down spontaneously. Their program consisted of individuals murdering prominent people, sometimes with bombs that killed many others. They didn’t get far and refused to cooperate with the socialists, who were into organizing.

Third, the chapter on the US is largely about the decision to become an empire, i.e. to subjugate other peoples by force. Many argued that this would contradict the very idea of a democratic America, which would best serve the world as an example rather than by imposing its ideals, if not quite its ownership, on colonial subjects. Teddy Roosevelt is the principal character, achieving national office after President McKinley was assassinated by an anarchist.

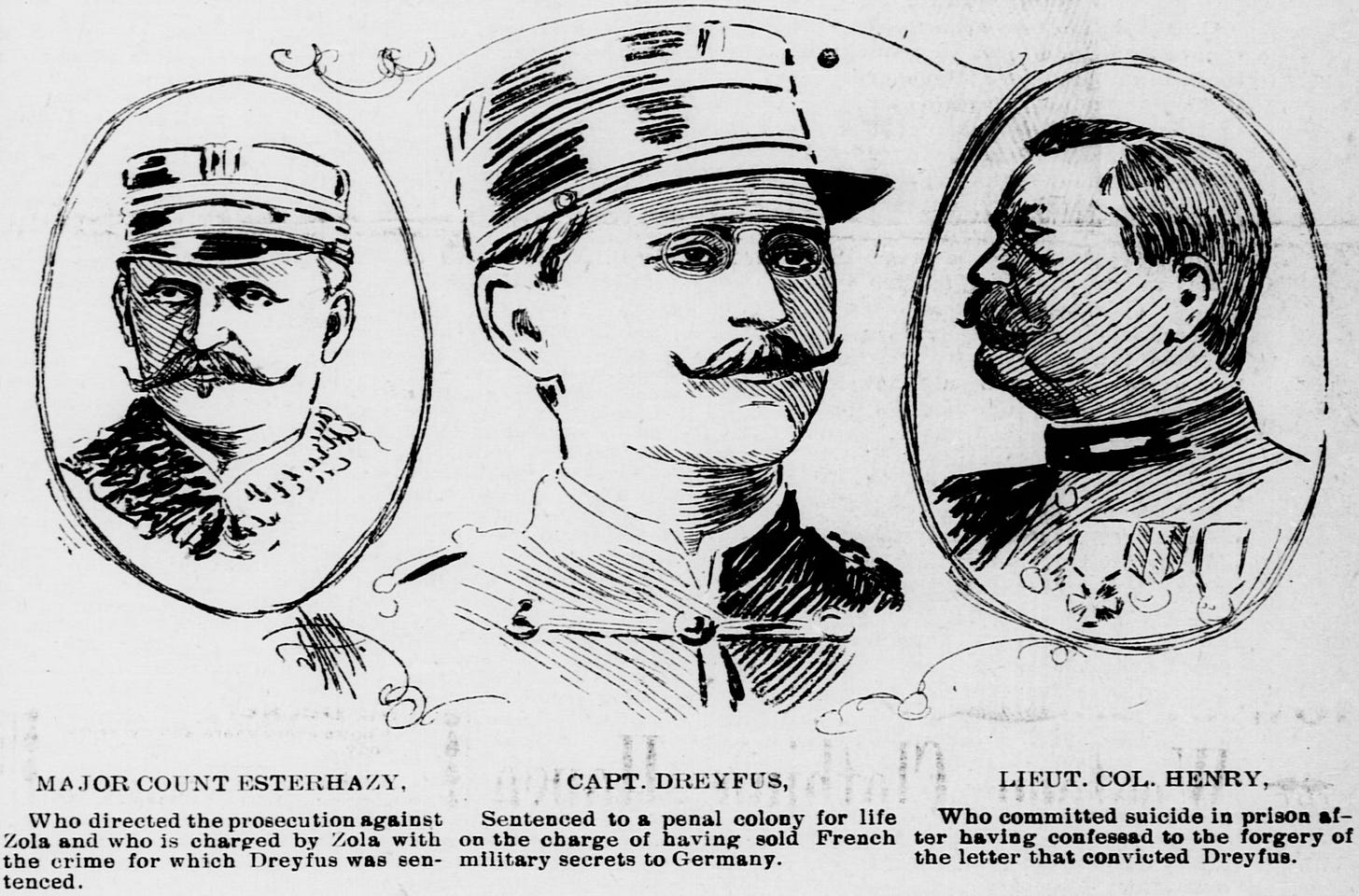

Fourth, there is France during the turmoil of the Dreyfus Affaire. This was by far my favorite chapter. At the time, France was split between traditional elites who wanted a more aristocratic, even perhaps royalist, regime versus proponents of modern democracy or socialism. The army embodied a combination of nationalism, honor, and conservative reaction, a kind of bulwark against the German threat as well as an opponent of democratization. That the army would stoop to scapegoating someone for espionage – made easier by the fact that Dreyfus was a converted Jew – and then crudely forge documents to hide their mistake was unthinkable yet, it turned out, demonstrably true. The result was nearly civil war once Emile Zola exposed all the lies. Interestingly, Tuchman did not believe that Anti-Semitism was the principal motive.

Fifth, some statesmen were attempting to create a new law of war and even to prevent its occurrence via controls on arms and industrial capacities. I found this chapter a bit dull and less satisfying. One of the gaps in coverage is economic development, which is mentioned here but not really explored.

Sixth, the chapter on Germany was somewhat odd, for the most part covering musical culture with a few references to Kaiser Wilhelm II, the autocrat who shaped the newly nationalist political culture for 30 years. The Kaiser started as a cult figure and ended discredited by any number of failures and scandals. I did enjoy learning about Strauss, but there was too much on him to the exclusion of others in my opinion. Tuchman could have explored modernism more deeply here.

Seventh, there is the “transfer of power” from the patricians to the democratic parties (the Liberals and Labor) in England. This picks up the thread of the first chapter, with the end of Balfour’s career, starting when the Tories, to their shock, were routed in the election of 1906. Though he hung onto power, he eventually decided to quit because he didn’t want to face the challenge of consolidating his leadership of the party and then transforming himself into a politician of popular appeal to the masses – that was left to Winston Churchill.

Finally, there were the socialists. Tuchman covers their transformation from Marxists that preached the revolutionary destruction of capitalism and bourgeois democracy to their split into innumerable factions as complex as the Protestant schisms during the Reformation. Some wanted to remain loyal to Marx’s vision, even though the facts seemed to contradict his predictions, i.e. the middle class did not get poorer, capitalists began to negotiate and eventually provided better working conditions, and participation in the economy did not devolve to massive monopolies but opened to entrepreneurs of all sorts. Others argued that participation in the democratic process offered the best route to changing their societies for the better. The principal character here is Jean Jaurès, who was assassinated by a nationalist for his advocacy of a general transnational strike to end war. In the end, of course, the proletariat proved more susceptible to nationalism, which was anticipated by many socialist factions, as Tuchman emphasizes.

This is a magnificent book, an extremely dense and absorbing read. While it is not a comprehensive history, it is a fresh and riveting popular history.

Related reviews:

Attempts to elucidate the sociological factors in 19th century history

History books tend to move between narrative and analysis, or put simply, a story vs. an interpretation of the forces and trends behind events. The narrative stresses the role and impact of individuals, while the analysis looks to abstractions and ideals. Osterhammel’s book skews as far to the analytic side as may be possible, in a sense it is a sociolo…

Evocative analysis of a watershed

This trilogy covers Europe from the French Revolution to the eve of World War I. Though Hobsbawm is often criticized as basic and obvious, I read his trilogy as a review and articulation of a number of issues that have long fascinated me, that is, the watershed developments that shape the modern world (e.g., the establishment of constitutional democracy…

Viennese intellectuals, artists and nationalists, with a dash of Freud

It is easier to say what this book is not than what it is: not a narrative history, not an analysis of causes, not even a basic introduction. It lacks clear definitions of the movements it is supposed to cover, such as liberalism, modernism, psychoanalysis, and the birth of mass nationalistic politics. That means that readers will either have to be fami…

The French artists who finally broke the mould

For anyone who is fascinated by the multifaceted artistic flowering of culture that began in the late 19th century, this book is a must read. It is about the emergence in France of an avant-garde, which began soon after the Impressionists and culminated later in Modernism and Surrealism. Shattuck attempts to explain this through 4 artists (Satie, Rousse…