Freeing the slaves in the British Empire

Review of Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire's Slaves by Adam Hochschild

Americans’ idea of freeing the slaves is inevitably connected to devastating civil war, which ignores the pioneering social and moral activism in the British as they voted to end slavery in 1838. Indeed, it is the first modern political campaign that had a goal rooted in empathy for others rather than self interest. This is the story of a remarkable and eccentric group of activists, who started a movement in 1787 and doggedly pursued their beliefs – amassing evidence, exclaiming their views, braving threats, and introducing legislation, all in an autocratic state. It was a revelation to me and a riveting read.

The kickoff abolitionist meeting was organized by Thomas Clarkson, a recent Cantabrigian and Anglican preacher. Having written an essay in Cambridge on the immorality of slavery, he had had a kind of revelation that its elimination would be his life’s work. Also in attendance was Granville Sharp, a musician, political agitator and pamphleteer; many of his causes, such as the frankpledge1, were obscure. Against overwhelming odds, they set an agenda that would dominate their lives and grow into a popular movement of unprecedented success. It should be noted that their moral qualms about slavery sprung from Christian ideals.

To get an idea of the odds against them, they were going after one of the principal pillars of Britain’s economy: the slave plantations producing cotton, tobacco, and most importantly, sugar. Indeed, the slave trade “triangle” arguably established the financial base of modern capitalism. According to this logic, manufactures (guns, tools, etc.) were brought to Africa, where they were traded for slaves. The slaves were then transported to the Americas, where they were set to work on highly organized plantations; their lives were so hard that up to 60% of them were expected to die from overwork in their first years as slaves, hence there was a need to continually replenish the labor supply. On the final leg, raw cotton, sugar, and other plantation products were brought to Europe, initiating a new cycle. If done right, each leg of the triangle was enough to create a fortune. As capital accumulated, it would finance investments in heavy industry, infrastructure, transportation, and military technology. By some accounts, the slave trade represented over 20% of Britain’s GDP in Clarkson’s time.

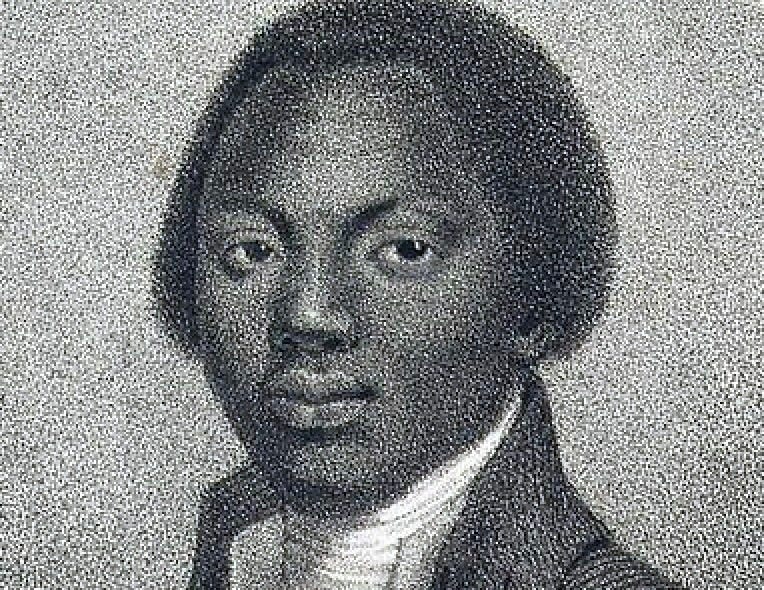

Clarkson in many ways was the first modern investigative journalist. Logging thousands of miles, he collected stories and incontrovertible documentary evidence of the cruelty of slavery as well as the soothing lies that were employed to justify it. For anyone who needs to become informed as to the inhuman excesses of slavery, Hochschild offers ample proof in the story of Clarkson’s quest. An idealist and zealot, he lectured throughout the country, wrote books, and exhorted his compatriots to join the cause. Though he made many enemies, Clarkson slowly built a coalition of remarkable supporters, ranging from a slaver-turned-preacher, John Newton (who wrote the hymn Amazing Grace), to Olaudah Equiano (author of the first slave memoir) and the cautious conservative MP, William Wilberforce, who had worked unsuccessfully for decades to introduce anti-slavery legislation.

Their initial goal was to end the trans-Atlantic slave trade, which they believed would lead to better treatment of existing slaves, i.e. they should no longer be worked to death, but needed to be better fed and treated in order to keep them alive. As a first step toward emancipation and the extension of human rights to all peoples, the abolitionists reasoned that this was a politically achievable goal. By 1807, it passed Parliament as law, soon to be imitated elsewhere, even by the United States. The results were, to put it mildly, disappointing. In particular, during the Napoleonic Wars and the political upheaval of the aftermath, the abolition of slavery virtually disappeared from political discourse for decades.

It was only with the revolution in Haiti, where slave leaders had taken the ideals of the French Revolution seriously, as well as a series of bloody rebellions in the Caribbean colonies that convinced the British that the cost of maintaining the system was too high. These chapters are key to understanding the experience of America’s neighbors in the south, whose histories are essentially absent from US textbooks. For example, I did not know that the British fought far longer than the French to recover control of Haiti, only for both to admit failure after catastrophic misadventures. Clarkson was the only original abolitionist who survived to see the outlawing of slavery in the Empire in 1838.

The story, of course, did not stop there. On the one hand, many emancipated slaves were brought to Sierra Leone, where they were deposited on a strip of land in the most inauspicious circumstances. While they struggled to survive, more were brought there. The leaders, many of them white, certainly had irreproachable motives, but they did not have the wherewithal to make a success of it. I do not know how they fared or the relation of this immigration to the recent civil war in Sierra Leone.

On the other hand, the treatment of former slaves who remained in the colonies was ambiguous at best, virtually unchanged at worst. Their labor was still needed, but the pay was disastrously low, the (already badly inadequate) paternalistic safeguards disappeared, and there was little developmental plan to improve their situations. If somewhat outside the scope of the book, I would have liked much more on this and will have to seek it elsewhere.

This is a dazzling reading experience, chock full of quirky characters, political innovation, and indescribably brutal cruelties. Hochschild brings a wonderful clarity to his writing and, so far as I can tell, his point of view is supported in the historical record. The book is so good that I believe it should become a cornerstone of American education, of an outcome that was radically different from ours. Critics charge that this version of the story presents far too rosy a picture of British attitudes and politics, that the struggle was harder and the results far worse than the conventional line.

Related:

The first slave memoir

This is a remarkable document of an extraordinary life. Abducted at 11 somewhere in Nigeria, Equiano survives the middle passage, takes on a new identity and name, and thrives to the point of purchasing his own freedom. Throughout, the reader experiences every stage of his life, from the terror and uncertainty to the achievement of a career as a sailor …

Slave experience, faith, and thought

In our political discourse, slavery is a minefield of stereotypes, tropes, and outright lies. Eugene Genovese’s book interprets slave life in the words of those who experienced and observed it firsthand. The result, in my opinion, is a wonderfully nuanced, largely qualitative portrait that digs more deeply into slavery’s rea…

The Civil War and its aftermath

I have some close, much-loved cousins in the South. Long before the advent of Trump, we had strongly divergent points of view. As a child, their father’s mix of radical libertarianism and open racism often shocked me, yet his religion made him impregnable. He vehemently denied that the Civil War was about slavery. In his view, it was about States’ right…

Our most consequential failure

Reconstruction was an immensely complex task: the South was supposed to be rebuilt but also submit to the transformation of its society and economy, ridding itself of the legacy of slavery. To complicate matters, it was imposed by the North. For obvious reasons, slaves had never had a chance to grow into the habits and customs of free laborers. Meanwhil…

The frankpledge was a community system of law, holding not just criminal perpetrators but everyone in the wider society was responsible for their actions.