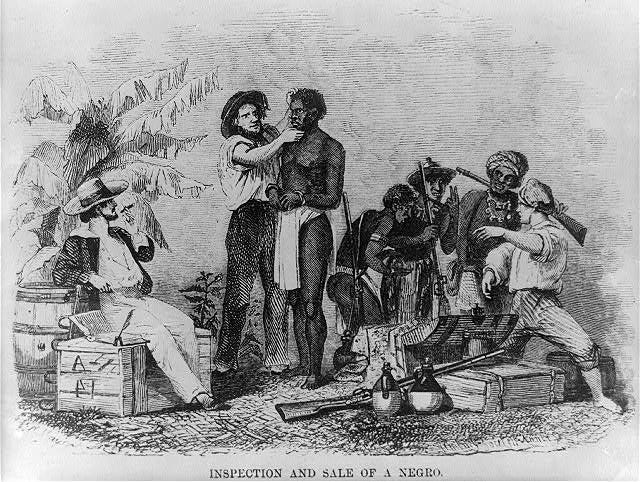

Slave experience, faith, and thought

Review of Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made by Eugene Genovese

In our political discourse, slavery is a minefield of stereotypes, tropes, and outright lies. Eugene Genovese’s book interprets slave life in the words of those who experienced and observed it firsthand. The result, in my opinion, is a wonderfully nuanced, largely qualitative portrait that digs more deeply into slavery’s reality than any other source that I know. Nonetheless, if the occasional doses of anthropology thrown in are useful, they do feel dated, i.e., Marxist.

Genovese argues that there are a number of core notions to the American version of slavery. It was a paternalist institution, implying reciprocity. In exchange for working, so the thinking went, the slaveholders would take care of their slaves in a fatherly fashion, because at any rate slaves were essentially incapable of adult responsibility; they offered them a home, food, and retirement "benefits" when no longer capable of working. Not only does Genovese challenge the self-serving hypocrisy behind this (it was designed to discipline slaves while justifying brutality), but he goes into great detail about the underhanded leverage it offered to the slaves to preserve their dignity and integrity to the degree they could. Slaveholder myopia, he concludes, was revealed in the shock and feelings of betrayal that they expressed when emancipated slaves left them – they had deluded themselves about the feelings of their property, their paternal charges; many continue to do so to this day: in their eyes, the slaves were inexplicably "ungrateful" for all that was given them.

Genovese next turns to the legal paradox of slavery. On the one hand, slaves were property, supposedly they existed principally as an extension of the will of the slaveholder. This made them objects, arbitrarily punishable with the greatest cruelty. On the other hand, slaves were recognized as having free will, necessitating legal responsibility for their actions but also an acknowledgement that they needed to be managed properly in order to get the best work out of them. The way that this paradox was solved, according to Genovese, was a reliance on local custom rather than a pan-regional legal regime, including legal protections and in some cases the right to self defense against white overseers; in this scheme, "bad" slaveholders could be ostracized by their peers, though what kind of an impact this might have had remains unclear to me.

Furthermore, the author explains, slaves developed their own versions of Christianity, which served simultaneously as resistance to the institution and as accommodation. To paraphrase Genovese, Christianity promoted acceptance of what had to be endured while offering visions of salvation and justice, tools to resist despair and dehumanization. Unlike slaveholders who asked forgiveness, it was a means for slaves to demand recognition and the right to some spiritual autonomy. The black preacher could become an idealist, a politician, an intriguer, a moral authority, or simply learned – in other words, power players. Of course, Christian services were also occasions for communal celebration and mutual aid.

In addition, once the brutal labor of land clearing was accomplished at an astonishingly high cost in lives (up to 30% were expected to die under these conditions), plantation work (which occupied about 1/3 of the total slave population) existed somewhere between traditional peasant labor and that of an industrialized proletariat. It operated in accordance with the rhythms of the harvest, but also required a much higher level of organization. Within the paternalist system, discipline was imposed from above, which, Genovese argues, did not prepare slaves for the post-war transition to a wage-based capitalist economy that offered them no paternalistic care, particularly when they could no longer work.

Finally, Genovese goes on at great length about the strengths of the slave family, which he argues became weaker only with emancipation. This flatly contradicts the assertion that weak familiar structure represented a trait somehow inherent in blacks. He argues, quite convincingly, that more research must be done in this area. In part, he was reacting to the assumptions in the Moynihan Report of 1965, which, he believed, projected current problems uncritically into the past.

These are very interesting concepts that added greatly to my understanding. However, the age of the book is revealed by the references that Genovese makes: there is Marx, of course, but also Gramsci and even Hegel, in addition to many academics then current, such as EP Thompson. However influential it was at the time, the policy-wonk obscurity of the Moynihan reference reflects the outdatedness of the book.

Perhaps someone has updated the content of the book, but I still think it sets a standard in the field. (If anyone has suggestions on contemporary books, please add them in comments.) This book does not offer a comprehensive narrative, but addresses the moment when slavery as an institution was more or less established. While there was some evolution, its approach is largely static. Instead, the book is organized around themes, the unity of which can be very difficult to discern in Genovese's occasionally abstruse and indirect style. You have to read the book slowly. It is about high undergraduate level.

Overall, this is a great and dense read. I warmly recommend it to anyone willing to make the effort.

Related:

How slavery laid the foundations of modern prosperity

The cotton industry represented the first step in the development of the modern industrial economy, according to Beckert. Slavery and ever-more-efficient state coercion (in subservient cooperation with private capital) were integral to its development. Global in scale, this convergence of factors would re-fashion the everyday lives of a majority of peop…

The United States in formation

This is a delightful narrative on that period in US history where the country was massively expanding, defining itself, and dividing into the hardened blocks – regional and ideological – that we can still see today. Taylor begins his book at the moment that the Federalists imploded and the Republicans, as led by Jefferson, em…

A uniquely compelling story of slavery and liberation

This is a remarkable document of an extraordinary life. Abducted at 11 somewhere in Nigeria, Equiano survives the middle passage, takes on a new identity and name, and thrives to the point of purchasing his own freedom. Throughout, the reader experiences every stage of his life, from the terror and uncertainty to the achievement of a career as a sailor…

Putting Africa at center stage

Howard W. French wishes to correct the impression, as popularly taught, that Africa was a backwater, an obstacle on the way to Asia, or was so underdeveloped that it was there to be exploited by Europeans. To do so, he sets out to prove that slavery was instrumental in the birth of “modernity”, a perspective that is slowly gaining recognition in academi…