Xerox invented the PC, then flubbed it

Review of Dealers of Lightning: Xerox PARC and the Dawn of the Computer Age by Michael Hiltzik

Beyond the complacency that Xerox' s phenomenal growth engendered in the 1960s, a number of habits became entrenched in the company's culture. The Xerox management hierarchy became one of rigid top-down control, which paid less attention to the opinions of its customers than the cost-and-quantity inputs of its financial models. Xerox remained a one-product company that had come to rely on patents to maintain its monopoly rather than on copier reliability and customer service, in spite of the company's huge sales force and its highly trained repair network.

As a result, while Xerox had set up a lavishly funded laboratory in Webster, New York, that research facility was more concerned with exploiting the remaining advantages of existing patents than developing new technologies for the future. In other words, Xerox was looking backwards, preserving revenue streams rather than creating wealth.

In spite of the confidence and pride of many in the top ranks of Xerox leadership, Chief Executive C. Peter McColough began to seek to diversify the company into data processing. After all, he was aware of the efforts of both IBM and Kodak to enter the copier field. Thus, he developed a fluffy visionary presentation, which claimed that Xerox would create "the office of the future" as well as a new "architecture of information".

To help him to realize this vision, McColough hired Jack Goldman from Ford, where as Chief Scientist he had long been frustrated by the lack of managerial interest in the innovations that his team had developed. Goldman came up with a plan for a research facility entirely separate from the applications-driven Webster facility, a place where basic research could be conducted at a remove from the everyday concerns of Xerox headquarters. McColough gave Goldman an unusually free hand, to open a kind of "research hermitage" whose mission would be to devise technologies "10 years ahead of their time".

For a variety of reasons, Goldman's timing was extremely lucky. In large part because of funding from the U.S. Department of Defense for the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), computer technologies were in an unusual state of ferment, an "inflection point" that carried great promise. On the one hand, the architecture of the mainframe computer reaching its limits by the early 1960s – they were massive and cumbersome machines that researchers had to share, with programming languages so obscure and counter-intuitive that non-specialists found them impossible to operate. On the other hand, the price of semiconductor memory chips was falling as their complexity and capabilities were increasing exponentially. Conditions were favorable for new product lines.

In addition, the ARPANET had just been invented. It could link computers into communication networks; it was the direct technological precursor to the internet. Finally, a number of visionaries in various universities and labs were pursuing a wide array of fundamental innovations; these included the development of "software" for graphical user interfaces, the "mouse" control to execute commands with a cursor on a television-like screen, and many other devices. If combined properly, these technologies promised to fundamentally transform the computer industry, making computers affordable for the individual as well as easier to use for the layman.

Moreover, with the Vietnam War swallowing up Defense Department resources, funding for ARPA had dropped abruptly by 1969. It had become, in Hiltzik's words, "a buyer's market for research and engineering talent."

Sensing an opportunity, PARC director George Pake invited Bob Taylor, one of ARPA's top research managers, to visit the facility he was establishing. During the mid-1960s, Taylor had run ARPA's research information-processing program for graphic user interfaces and computer networks. He was gifted, according to his peers, with an "instinctive grasp of the promise of man-computer interaction". Perhaps more important, he was reputed to have "an exceptionally high degree" of leadership and people skills: he could find talent, motivate people to work together towards a common goal, and yet refrain from imposing his own solutions on a problem, in effect allowing the best to do what they did best. In July, 1970, Pake hired Taylor to lead the Computer Science Laboratory (CSL) at PARC; he immediately (and successfully) set out to lure the best researchers to PARC from the network he had created (and funded) while at ARPA.

Taylor created a flat organization, in which CSL members reported directly – and only – to him. This placed him at the heart of the laboratory, aware of what everyone was doing, what they hoped to accomplish, and where they needed to improve. While he directed research with clear end goals in mind, Taylor operated largely as a mediator of ideas, trusting team members to devise the optimal combination of solutions to a given problem or goal; he knew that they were far better qualified than he was to address the various technical challenges. In his view, by helping his researchers to communicate with each other and understand the gestalt of CSL's evolving technologies, he would ensure that the pieces of each project would fit together into a concrete product that would be able to function. It was, in Hiltzik's words, as if CSL "worked like orchestra members, composing and rehearsing a symphony at the same time." This is very similar to the way that Robert Oppenheimer ran the Manhattan Project.

The atmosphere of CSL was freewheeling and personable, full of excitement. They formed a peer group of pioneers, a self-conscious elite that resembled a cult. Taylor's team eventually totaled between 40 and 50 members, by some measures fully two-thirds of the best computer researchers then alive.

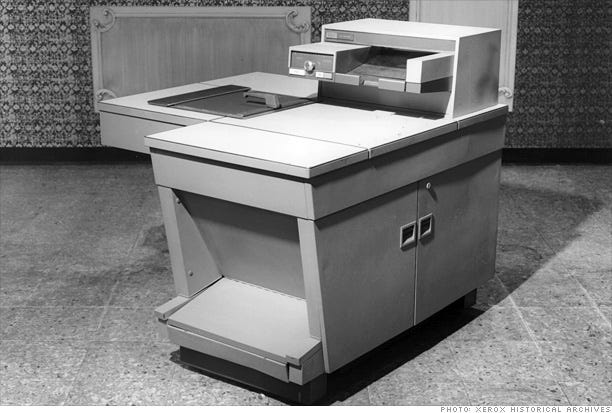

Over the next three years, CSL created the Alto, the first programmable personal computer that was user friendly: with mouse, a graphics-oriented user interfact, with "icons" and overlapping "pages", an object-oriented programming language and even an ethernet capability.

Unfortunately, few at Xerox headquarters understood the importance of these developments. From its beginning, most executives at Xerox headquarters viewed PARC as a kind of uncontrollable island of insolence and arrogance. For their part, PARC researchers viewed headquarters with open disdain at the leadership's inability to understand what PARC was doing. The mutual distrust between headquarters and its Palo Alto lab neither encouraged Xerox executives to learn about how PARC's inventions might fit into the modern office nor enabled PARC's managers to sell their inventions to the company's manufacturing units.

Worst of all, at this time – the mid-1970s – Japanese copier manufacturers executed a stunning strategy that succeeded in turning Xerox's supposed comparative advantages (its sales forces and repair facilities and its reliance on patented bits of technology) into liabilities. The Japanese copiers were easier to install, much cheaper (customers could buy them outright rather than lease and then pay for individual copies), and far less costly to fix. Suddenly, the company found itself in a fight for its life, after more than a decade as an unchallenged monopoly that had grown flabby.

As a result, PARC's incredibly fecund inventions never got the attention of top Xerox managers, who were too busy studying the TQM methods of the Japanese (an effort that did eventually pay off). As such, it was Apple, Microsoft, and IBM that used Xerox PARC’s ideas to dominate the emerging industry for affordable personal computers.

Finally, the author does add a lot as a reporter, including an interesting interpretation of Jobs' mythic visit to PARC in 1979: rather than the entrepreneurial epiphany it was touted as, Hiltzik argues that Jobs and his team knew exactly what they were looking for and used PARC's inventions less as an inspiration than as a confirmation of what Apple was planning to do. This chapter alone is worth the price of admission. There can be no doubt that Hiltzik is a thoughtful observer who pounded the pavement: he gets the basics right and unearths many details that will be of use to academics.

This is a fascinating tale, but much of this book gets lost in the details of software development, arcana that only true geeks or technology historians should care to look at such a level of minutia. Unfortunately, Hiltzik tries to make it into something far more heroic and dramatic than I think it should be, complete with endless – in my view needlessly romanticized – characterizations of the geeks that did it. While this perspective is personal, and I do not mean to demean the audiences that it would please, I am trying to warn general non-specialist readers (like me) that it is in certain respects too detailed and over-reaching. It is a great reference book, but not always a fun read.

There is a subtext to the story that Hiltzik and other Silicon Valley journalists do not care to develop. In my view, there are in fact very few inventions that have served as the driving force of Silicon Valley. In just about every sense, the Alto is the basic prototype of the personal computer of today – it has been refined and incrementally improved, but hardly changed in any fundamental way since 1973. That is the basis of the information revolution, but also a sign of how over-hyped its accomplishments have been.

Related:

Story of application of TQM, to save Xerox

My fascination with Xerox started in the early 1960s. My mother, who worked in an office with a Xerox machine, would occasionally copy things for me, like my Marvel comics. I even got to operate it myself. The copier was a runaway commercial success, only to face increased competition from Japan in the mid-70s and then teeter on the verge of bankruptcy.…

The Manhattan Project, from scientific discovery to detonation

This book has it all: fascinating personalities, fundamental scientific discoveries explained with clarity, and the birth of political issues that are as relevant today as they were 80 years ago. That it is almost certainly the best book on the development of the atomic bomb is in itself remarkable, as the field is already overcrowded. Rhodes makes an e…