Story of application of TQM, to save Xerox

Review of Prophets in the Dark: How Xerox Reinvented Itself and Beat Back the Japanese by David Kearns and David Nadler

My fascination with Xerox started in the early 1960s. My mother, who worked in an office with a Xerox machine, would occasionally copy things for me, like my Marvel comics. I even got to operate it myself. The copier was a runaway commercial success, only to face increased competition from Japan in the mid-70s and then teeter on the verge of bankruptcy. This book is the story of CEO David Kearns, who turned the situation around in the 1980s. It offers an interesting, if incomplete, corporate bio.

During the Great Depression, patent clerk Chester Carlson was driven by a passion to invent an office copier. Toiling for years in obscurity, in October 1938 he finally obtained a series of patents on a five-step process: 1) charge a photoconductive template, the "selenium drum"; 2) shine light through an "original document," erasing a mirror electrostatic image from the template; 3) dust it with ink powder that would cling onto the remaining electrically charged portions; 4) press the pattern onto a blank page; and 5) bake the ink into a permanent "copy".

In spite of his patents, it took Carlson nearly another 10 years to convince a company, the Haloid Corporation, to license and develop the technology, soon to be called xerography. From 1947 to 1960, Haloid invested over $75 million in the process, in effect betting the entire company on the outcome. Its first copier, the 914, was perhaps the most technologically complex office machine that had ever been marketed.

In spite of the technical challenges and near-universal skepticism, the 914 became a blockbuster product: operating at the touch of a single button, it was user-friendly and needed only plain paper rather than the chemically coated varieties of its competitors. Most important, it seemed to answer some unacknowledged need. Overnight, it became the must-have item for the modern corporate office. Haloid, which renamed itself the Xerox Corporation, saw its revenues rise from US$32 million in 1959 to US$1.13 billion in 1969.

The secret behind the rapid acceptance of the 914, whose manufacturing costs were ten times greater than its nearest competitor, was Xerox's leasing scheme: for a low monthly rent of US$95, the 914 was delivered ready for use; the first 2,000 copies were free, but after that point the additional copies were "metered", costing about 4 cents for each push of the button. Barely able to keep up with the demand, the company grew so rapidly in the 1960s that the hiring of qualified personnel became its greatest problem.

Perhaps because of its phenomenal growth in the 1960s, a number of habits became entrenched in the company's culture. The Xerox management hierarchy became one of rigid top-down control, which paid less attention to the opinions of its customers than the cost-and-quantity inputs of its financial models. At the end of the decade, Xerox was a one-product company that had come to rely more on patents to maintain its monopoly than on copier reliability and customer service, in spite of the company's huge sales force and its highly trained repair network.

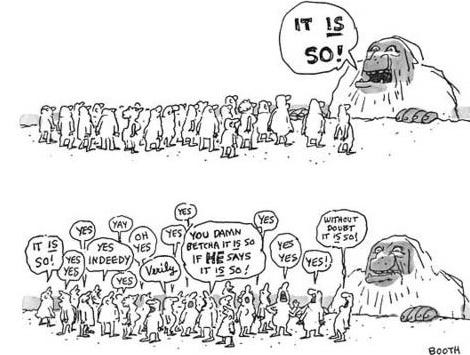

Just prior to the death of Joseph Wilson in 1971 – the original leader who had decided to develop the xerography process – a large group of managers was hired from the Ford Corporation to impose more order on the dynamic, yet chaotic Xerox. Dubbed the "Ford Men", the new team was composed largely of bean counters. They immediately began to institute a number of rigid control procedures, buttressed by formalistic "trend analyses" and a finance- and accounting-dominated vocabulary; this alienated the sales and marketing enthusiasts from the early days of Xerox. Executive decision-making became procedure-driven, often based on computer models that focused on cost containment, operational efficiency, and the maintenance of revenue streams. With little consultation of the lower-echelon workers for input regarding customer needs, many in upper-level management tended to operate from a number of petty dogmas, such as "avoid moving the original" for fear of damaging it, or prioritizing ease of use over reliability and image quality.

Then, in December 1972, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) filed a complaint against Xerox for "unfair methods of competition in commerce." At the time, Xerox held 95% of the market for plain-paper copiers. After an intense period of litigation, Xerox negotiated a settlement with the FTC. Among its terms, the company agreed to license its most important technological advantage: the selenium drum that enabled its copiers to print on plain paper. While some were uneasy about the loss of this exclusive patent, others assumed that Xerox's leadership in the market was so undisputed that no one would be able to overtake it. Taken together, the stage was set for new competitors from Japan.

To the shock of many Xerox leaders, in the mid-1970s Japanese manufacturers came up with a number of basic innovations in design, greatly enhancing the reliability and performance of their copiers while reducing their cost. For example, liquid toner eliminated the need for the heating elements that were required to bake Xerox's powdered ink. Canon, known as a camera manufacturer, consolidated the principal elements of xerography technology into a single disposable cartridge, which was quickly and easily replaced by less skilled repairmen. Moreover, with miniaturized and less expensive copiers, Japanese manufacturers were able to sell them as a one-time expenditure for between US$3,000 and $6,000, eliminating the expense of both the renewable lease and ongoing payments for individual copies. Finally, the Japanese were also able to hire independent distributors with lucrative direct-sale contracts. With this stunningly executed strategy, the Japanese manufacturers succeeded in turning Xerox's supposed comparative advantages into liabilities.

Panicked, the top leadership at Xerox had turned its attention to investigating the methods of Japanese companies, in particular the techniques of total quality management (TQM), which would occupy the attention of David Kearns, the new Xerox CEO, into the 1990s. This book shows how they did it and how well it worked, but it stops short of showing how the company should diversify out of copiers. Essentially, Kearns argues that he held all employees accountable for the quality of their work in technology and services, keeping the needs of the customer as a priority.

Also little mentioned is Xerox’s failure in the early 1970s to commercialize the inventions it had sponsored at PARC, that is, the essential elements that resulted in the personal computer revolution. Xerox invented virtually all of the basic software that is still being iterated today, but could not come up with marketable products with it, in part because Kearns didn't know what he had! So Jobs visited the lab and used their ideas for the first Mac, as silicon valley legend would tell it. Of course, PARC employees were unlucky in that Xerox was fighting for its life at the moment that their inventions came to fruition. It is one of the great missed opportunities in business history.

This is a really interesting book, in particular for its diagnostic of Xerox, but it ends too early to tell much about how the company would transform itself to remain viable. After Kearns’ departure, it was beset by a series of accounting scandals and still has not reinvented its identity. It has survived into the 2020s, but never regained its élan.

Nonetheless, this makes for a compelling read about TQM and the reasons for the decline of a great American corporation.

Related reviews:

How Xerox invented the PC then flubbed it

Perhaps because of Xerox' s phenomenal growth in the 1960s, a number of habits became entrenched in the company's culture. The Xerox management hierarchy became one of rigid top-down control, which paid less attention to the opinions of its customers than the cost-and-quantity inputs of its financial models. At the end of the decade, Xerox was a one-pro…

Review of The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization by Peter Senge

All too often, when reading a book in my former field (business writing) I found myself ready to dismiss just about anything as mediocre, no matter how popular or praised. Well, this is one book that I found really excellent – for content, for clarity, for sincerity, for the stories reported in it.

Clear, realistic, and inspiring in its banality

This is a good business book: it is eminently practical, well written, and in my own investigations I have seen exactly what the author is talking about. Stories are also interwoven in the book in a way that is a useful and interesting. They greatly add to the text rather act as filler to stretch it to book length. Indeed, this is one of the few busine…