The moment when Rome became an Empire

Review of The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265-146BC by Adrian Keith Goldsworthy

This book is for those seriously interested in the three Punic Wars, the moment when Rome decisively left the Italian peninsula to become a superpower in the Mediterranean. It starts off pretty dry, with a long discussion of the states of Carthage and Rome at the time that the conflict began. While Goldsworthy includes material on their political systems and tidbits on their civilizations, most of the book is a dissection of their military machines.

The Romans relied primarily on a reservoir of manpower from farm owners in Italy, which included rather loyal Latin and Italian allies in addition to some Spanish mercenaries. They were driven largely by patriotism, were governed in accordance with the yearly elected consuls of the Republican system, and were essentially amateur soldiers. With this reservoir of human capital, the Romans’ great advantage lay in the application of overwhelming brute force, which they applied until their adversaries were exhausted; the decisive difference was that the Romans absolutely refused to stop or accept defeat. Politics was inextricably linked to military action, though the consuls were patrician aristocrats seeking glory for parochial political motives and hence also military amateurs. Up to this point, there was little refinement or subtlety to their tactics and diplomacy. That was about to change.

In contrast, the Carthaginians had a dispersed empire that spanned the western Mediterranean in a C-shape, colonies that had long broken free from their origin in Phoenicia (i.e., semitic Lebanon). There was a core of Carthaginian aristocrats that controlled all of the myriad ethnic groups under their influence, mainly for purposes of trade – mostly maritime – and only secondarily for military application; they excelled at nuanced diplomacy and negotiation. In addition, there was a caste of professional military officers, who managed a huge mercenary army and various allies that operated in somewhat ethnically separate units (i.e., as wings in an eclectic army, which fundamentally effected their cohesion). With their experience from an early age, the military leader caste operated more from intelligent tactics and highly developed specializations, in particular in naval maneuverability, the use of elephants to overawe their adversaries on land, and flexible military formations. The contrast with Rome could not be more stark.

The first Punic War broke out over control of Sicily, which was a patchwork of Carthaginian, Greek, and Italianate city states. After many indecisive skirmishes, Rome sent troops - the first time they left the Italian peninsula! - and built its first navy. In time, after many disasters (some natural, others due to lack of experience), the Roman navy beat Carthage by attrition as did the Roman Army. Carthage sued for peace, agreed to pay massive indemnities (which they did), and gave up Sicily and many other possessions for the promise of peace as subordinates. I have seen their colony off of Marsala, Sicily and have been fascinated with their culture ever since. Carthage offered a very different possible future.

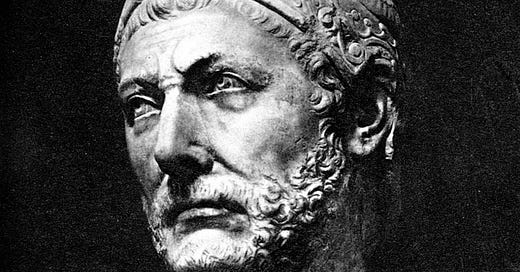

Hannibal, of the Barca military clan, was assigned Spain, which he consolidated for Carthage to the growing disquiet of Rome. It was clear from the outset that he was an extraordinary military talent; though little is known about his character or psychology, his motivation, in Goldsworthy's opinion, was to weaken Rome as a prelude to negotiation rather than to destroy it, in accordance with the Carthaginian way. As tensions grew, in 218 BCE – after more than 20 years of peace – at 26 years of age, Hannibal moved a massive army across the Alps into Italy, an unprecedentedly movement of troops in Europe, complete with elephants, and attacked Rome at its heart. He gathered many followers along the way (in a scale of tens of thousands, of Spaniards and Gauls, but, significantly, rarely of Latins or Italians); he had to feed, arm, and inspire them. This he did by winning early significant victories, ravaging the countryside, and stealing what he could while vainly attempting to recruit southern Italians.

The Romans had never faced such a threat, from a strategist and leader of genius who adapted his tactics to their weaknesses, e.g. Cannae: he enveloped and attacked from behind a massive Roman phalanx that could only march forward and hence was unable to regroup and reform, resulting in a slaughter of nearly 50,000 Romans, or 1/10 of the entire potential military manpower in Italy. In all later military literature, Cannae became a touchstone.

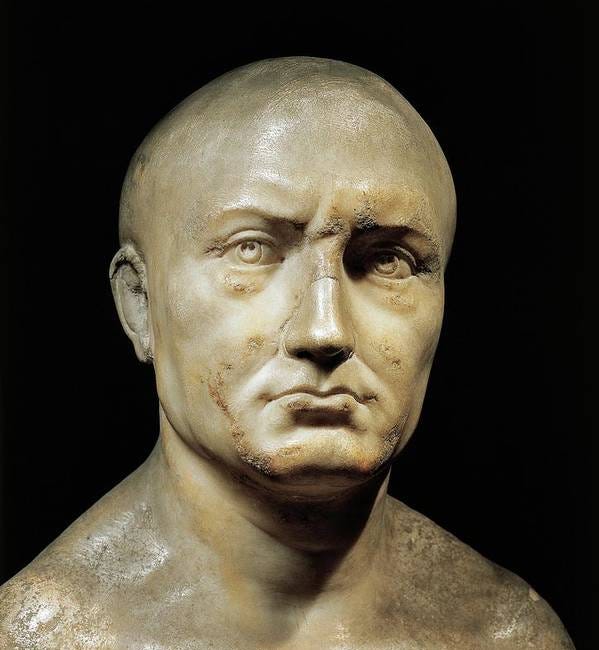

Against their military culture, the Romans voted in a dictator for 6 months, Fabius Maximus, who harassed but would not engage Hannibal in any decisive battles (named the Fabien strategy). It bought Rome time to regroup and attack in North Africa, once again bringing its adversary down by superior force. Never defeated in Italy, Hannibal had been ordered to withdraw in order to defend Carthage – his only failure – and was exiled soon after the defeat. His tactics, many of them perhaps apocryphal, inspired Romans to think the unthinkable for the remaining life of the Western Empire; Hannibal was the indispensable catalyst to Rome becoming a first-rate global power. Rome emerged with a far better trained army under its own military genius, Scipio. This was the true beginning of the Roman Empire, a century prior to the fall of the Republic. The third Punic War was shamefully manufactured by Rome and consisted of a siege of Carthage, which was completely destroyed in 146 BCE.

The difference between the 2 Empires was that, contrary to the expectations of Carthage, Rome regarded the fight as one to the death: the Roman republicans refused all compromise and instead of giving up, resolved to fight on no matter what the sacrifice, even at the risk of total annihilation. This explains why in the end, when they had the means in spite of Carthage's behavior as a good subordinate, the Romans resolved to decisively destroy any rival power. Rome then went on to completely dominate the entire Mediterranean, the undisputed superpower of the ancient world for the next 600 years or so, in large part from what it learned during the conflict with Carthage. This is military history at its absolute best.

Goldsworthy is very good at fleshing out, in a moderate way that does not imply a deterministic argument, the problems that the Roman Republic then faced. Most importantly, there was a dwindling pool of military manpower, traditionally recruited from yeoman Roman farmers. In this period, the smaller independent farms were declining as slaves were imported to work massive latifundia, severely impacting this traditional source of manpower. Moreover, because campaigns were longer lasting, often on foreign soil, farmers were increasingly suffering economically from long absences.

In addition, in the wake of the Gracchi brothers’ reforms, the Republic’s institutions had become excessively competitive - Tribunes of the plebs could veto measures voted in the largely Patrician Senate, causing the political system to stall. While opening offices to populist candidates, this promoted sleazy maneuvering to gain power at the expense of the interest of the nation. For example, Scipio, who was not a good politician, was forced out after his vitories, chose exile, and died while relatively young. This squandered a unique talent.

These trends eventually culminated, with the Marian reforms, in the creation of a professional military. Its loyalties lay not with the Republic but with the generals to whom the proletariat grunts aligned themselves - generals like Marius and Sulla became “guarantors” of their security and life style, which the Republican Senate refused to grant instead preferring to fight in short-term political machinations. The refusal to consider the legitimacy of the demands of the Italian and Latin allies perhaps also rendered a “social war” inevitable. In this view, the rise of a Caesar might have been inevitable.

I do have criticisms of the book. I wanted much, much more on civilization and politics, particularly of the Phoenicians and what they built in Carthage. The details (predominantly) as included are also very spare, offering much less of a feeling for life at the time than I had expected after Goldsworthy's absolute masterpiece bio of Caesar. I also would have wanted illustrations (there are none) and more detailed maps. Finally, there is not a good further reading section, for which any serious reader would hunger.

I think that Adrian Goldsworthy is the best popular historian on Rome working today, at about the undergraduate level. While he has a beautiful writing style, he also is thoroughly versed in the scholarly issues, which he brings into the discussion without the excesses of academic proofs and petty oneupmanship. It is a very difficult balance to strike and the author does it to perfection. Rather than make comparisons with the present, the author's purpose is to explain the wars in historical context, from a strictly military point of view; in this way, to his great credit, he refuses to make fatuous generalizations than the twit pundits who have way too much to say about things they know way too little about.

This is absolutely essential stuff that any student of history or Rome buff must know. Hence, it is one of the basic reads that will stand as a classic in my opinion.

Related reviews:

The other great classical civilization

I have always been curious about Carthage. This great power has long been defined against its adversaries, the Greeks and the Romans. Having left no real literary legacy, Carthage is like the dark matter of that period: you know it is there, but can't quite see it except as a gravitational well. And yet, it is portrayed as the

The evolution of the Roman military machine

This book follows the development of the Roman Army from its mythic founding (in 753 BCE) to the collapse of the West in the 5th century CE, over nearly 700 years. The writing is dense and to the point, skipping narrative treatment for hard-nosed analysis. What made the Roman Army unique”? How did it adapt to different circumstances? What was interplay …

Case studies in Roman military leadership

In this book, Goldsworthy seeks to answer the questions, why did some Roman generals succeed outstandingly and what lessons we can draw? To answer them, he looks at a series of generals from the Punic Wars (3rd century BCE), which ensured Rome's survival and determined its future course, to the last great general, Belisarius, who tried and failed to rec…