The Magna Carta failure

Review of King John - Treachery and Tyranny in Medieval England: The Road to Magna Carta by John Morris

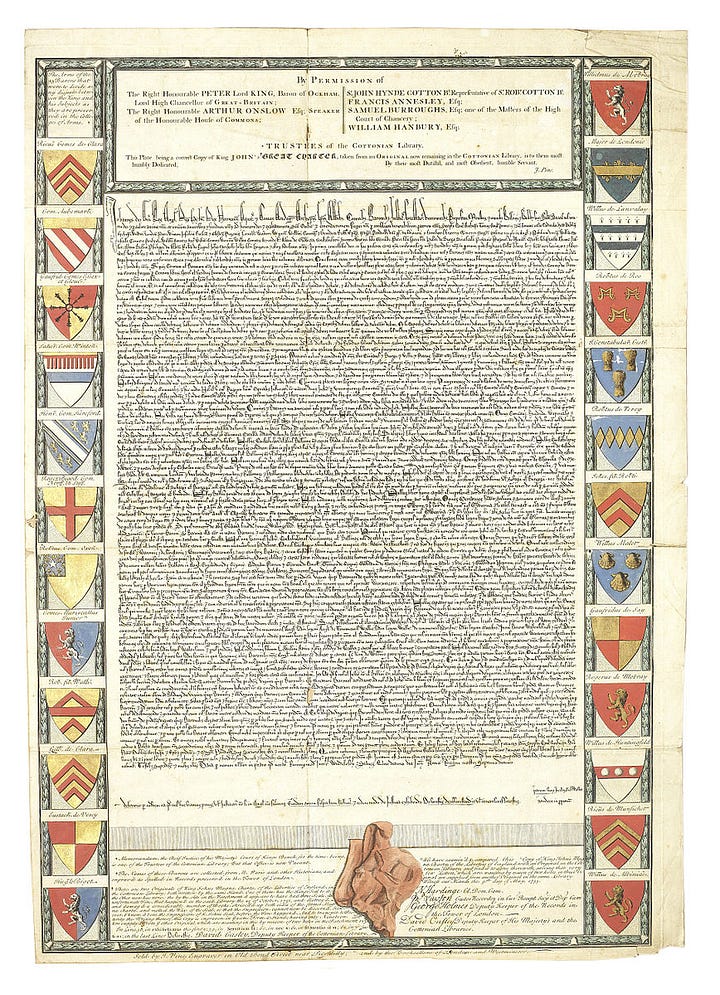

King John, the youngest son of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine, signed the Magna Carta at the end of his reign in 1216. This is viewed as a fundamental step towards constitutional monarchy and even representative government. How did this moment come about? Did it mean what tradition claims? Was it even effective? In this masterful narrative, Marc Morris sets out to answer these questions.

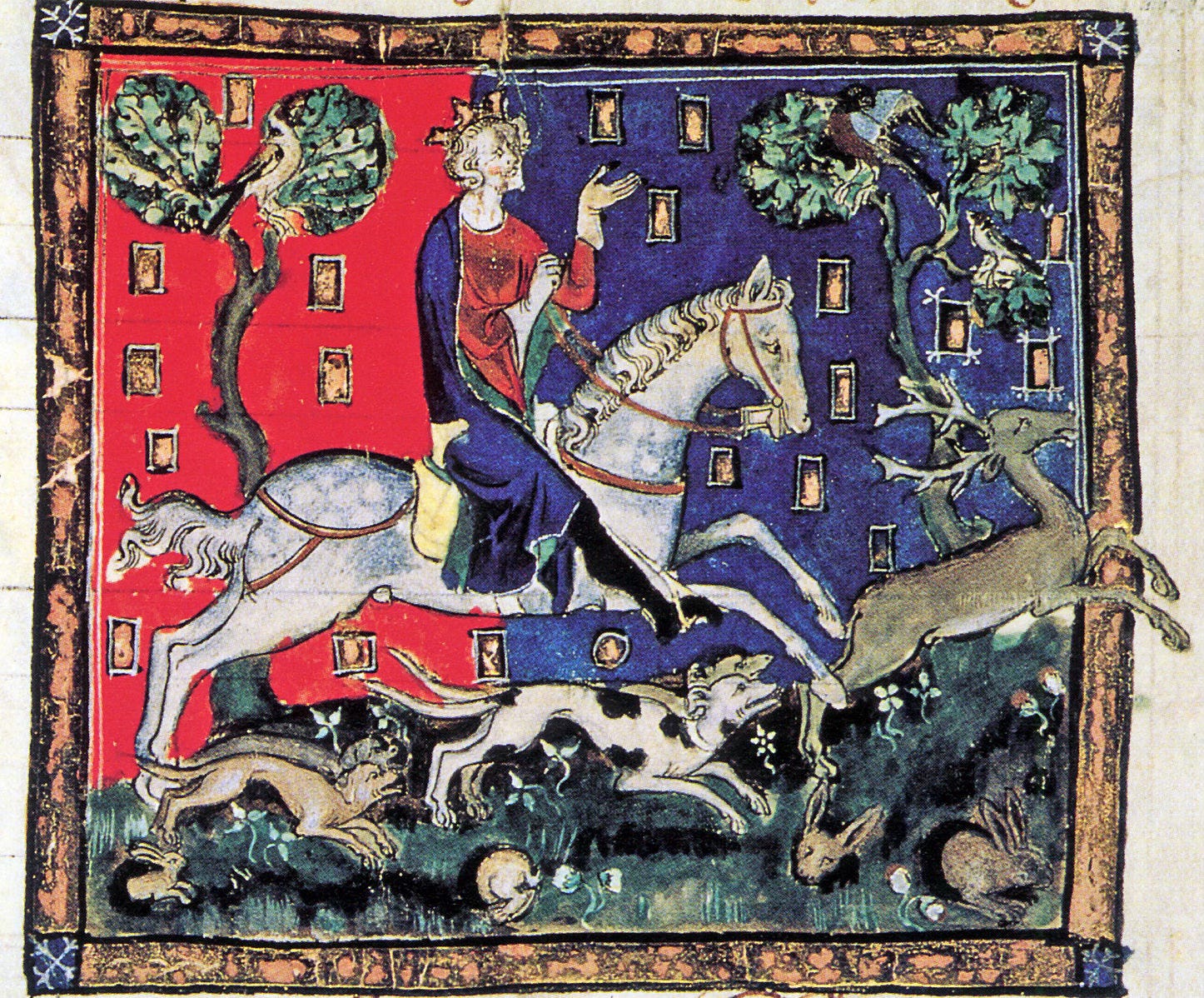

The Plantagenet Dynasty was begun by Henry II, when he married Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1152 and acquired a huge swath of southwestern France, forming the Angevin Empire. They had 8 children, of whom John was the youngest son and, apparently, relatively neglected. Henry treated his sons callously, denying them power and domains (read, resources) while stringing them along with promises and manipulating them to fight each other. The sons paid Henry back in kind, allying with his enemies and intriguing incessantly. He died in 1189.

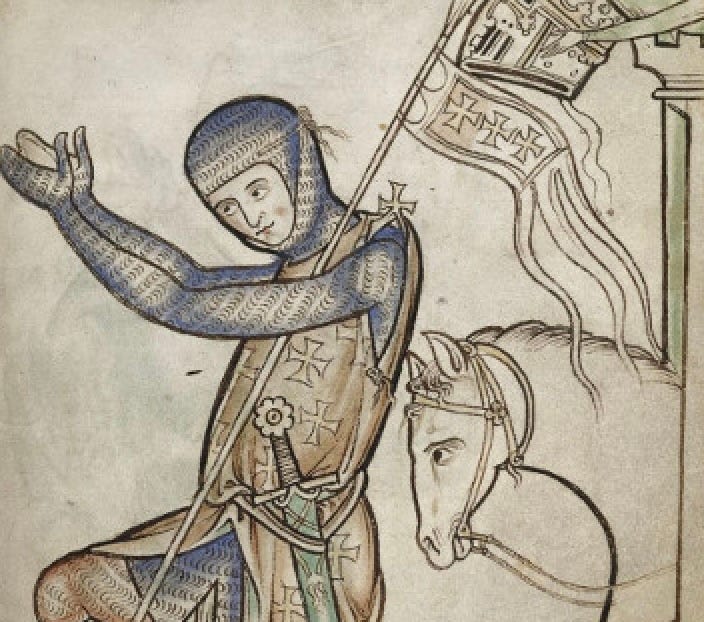

Because John had attempted to usurp the throne of his brother, Richard the Lionheart, when he was on crusade, he severely damaged his reputation with his future vassals. Nonetheless, the three eldest sons died young, leaving John as presumptive heir to the Kingdom (r. 1199-1216).

His greatest problem was that there was a rival legitimate claimant, his nephew Arthur. Prior to reluctantly swearing loyalty to John, many of his vassals had championed Arthur – they feared John was untrustworthy and treacherous. At the age of 15, Arthur escaped from John, who was planning to imprison him for safekeeping. Upon his recapture, John ordered him blinded and castrated, which his henchmen refused to do. Nonetheless, Arthur mysteriously disappeared, probably murdered in John’s custody. This ruthless cruelty would taint his regime irrevocably.

Soon after his accession, John faced a grave challenge. King Philip Augustus of the Capet Dynasty began a concerted attack on the Plantagenet territories in France, quickly taking Normandy and threatening Anjou. This was a mortal blow to the honor of the Angevin Empire and was to shape John’s career – from then on, to reconquer and protect his lands, he was desperate to raise money in any way he could.

If John had a spark of genius, it was in the means he exerted to extort money from his vassals, subjects, and the Church. Not only did he raise every customary fee of feudal obligations, such as the scutage, but he wantonly invented reasons to fine and confiscate their lands. Of course, this alienated his vassals, whom he treated with cruelty and arrogance. Beyond squeezing their resources, he seduced their women, demanded hostages to compel loyalty, then deliberately starved many of them to death in his custody. It was one of the worst tyrannies of the age. Eventually, John had exiled so many monks that the Pope excommunicated him, a grave threat to his legitimacy – his vassals could renounce their vows and vote in a new king. This got his attention and he began to back peddle to a degree.

According to Morris, John proved dangerously incompetent. As a politician, he failed to cultivate reliable allies, refused to listen to their complaints, and demonstrated again and again by his caprices that he was not to be trusted. This made him almost universally hated. Even though he had mobilized phenomenal resources for his planed military campaign in France, various rebellions he had to crush close to home rendered him unable to concentrate on the recovery of the eastern portion of the Angevin Empire. Instead, he faced perpetual whack-a-mole rebellion, forcing him to scramble to northern England, Wales, and Ireland as well as central England. When in 1213 he finally left to campaign in France with a much weakened force, in the battle of Bouvines, he lost badly to Philip Augustus and barely escaped to England. What he had struggled to accomplish for the 15 years of his reign came to nothing – western France was irrevocably lost.

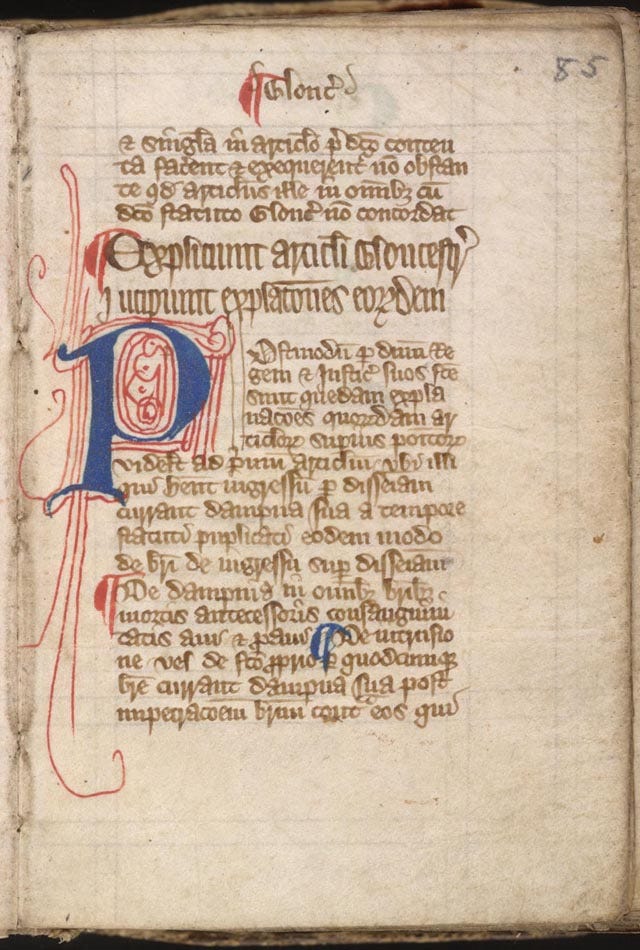

In the meantime, dissatisfaction with his rule had reached catastrophic proportions. As rumors of assassination plots increased his paranoia and cruelty, his barons and earls banded together to present John with their demands, leading to the long negotiations that would culminate in the Magna Carta. In 1215, John agreed to abide by a new set of rules, constraining many of his powers, righting the long list of his injustices, and setting up a consultation procedure to monitor the behavior of both sides.

Unfortunately, to no one’s surprise, the agreement unraveled in a matter of weeks, throwing the country into large-scale civil war. At least in its first incarnation, the Magna Carta was a complete failure. A near-fatal blow to John was the fall of London to rebels, which cut off access to his treasury. Even worse, seeing the civil turmoil, Philip Augustus mounted an invasion force into England, seeking both to conquer territory and turn the allegiance of John’s purported allies to himself. It was in this atmosphere that John entered his final illness, perhaps dysentery or heart attack. He died in 1216, leaving his kingdom to his son, Henry III, who was 9 years old. Depriving his vassals of a motive to fight, they rallied to Henry, whose guardian was none other than William Marshall. Soon, Philip Augustus was driven from England.

To say the least, King John was one of the worst kings in England’s history. Virtually all of his strategic endeavors ended in total failure, half the territory of the Angevin Empire was lost, and his subjects felt compelled to rebel against his tyranny. Indeed, even the first Magna Carta proved worthless, except to later generations that negotiated binding compromises for the establishment of a constitutional monarchy.

John Morris covers these developments in luscious narrative detail. He sticks to what can be known and acknowledges clearly when he speculates, which given the paucity of sources is quite often. I often felt a bit lost in the details, but for the most part enjoyed the book and recommend it to serious history enthusiasts.

Related:

Knighthood explained in a unique biography

Though William Marshal shaped his time and achieved fame in his lifetime, he was largely forgotten until the only copy of an epic poem about him was rediscovered in 1861. This book follows the poem, piecing together his remarkable career and life from a variety of sources. He was the archetypical knight: chivalrous, Christian, an ethical killer, a fierc…

Primer on the Feudal Age

Beyond her husbands and sons, less is known of Eleanor of Aquitaine than her Hollywood image would imply. She is a person on whom it is easy to project one’s fantasies or concerns, a player at the center of decisive intrigues and power plays, even a proto-feminist to some. In this book, she serves as an actor on the feudal stage, a concatenation of murd…