Beyond her husbands and sons, less is known of Eleanor of Aquitaine than her Hollywood image would imply. She is a person on whom it is easy to project one’s fantasies or concerns, a player at the center of decisive intrigues and power plays, even a proto-feminist to some. In this book, she serves as an actor on the feudal stage, a concatenation of murderously ambitious princes, twisted loyalties, petty wars, and religious scruples.

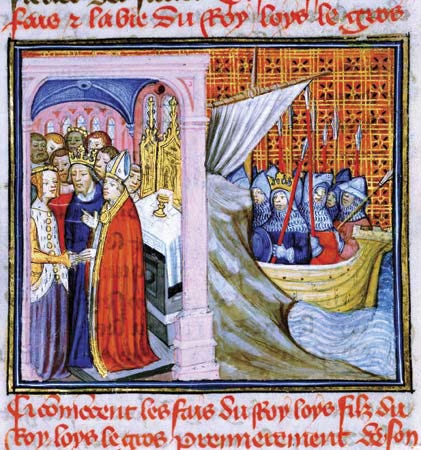

Eleanor was a rich princess of Poitiers/Aquitaine of Western France, whose “ownership” of these provinces made her a valuable marriage prospect as she brought all of her vassals with her – they would swear allegiance to her husband under the right circumstances. She married very young to become the queen of France with Louis VII (of the Capet dynasty), when “France” represented barely more than the larger Paris region. More a monk than a husband or lover, Louis bored her. She accompanied him on the 2nd Crusade, was feted in the greatest Christian courts, then got her marriage annulled (ostensively due to co-sanguinity). She then married a Norman Prince, Henry II, even though she had perhaps been his father's lover. Henry became the King of England, beginning the Plantagenet dynasty, which Eleanor expanded into western France. Though officially vassals to her ex-husband Louis VII, their power – and Henry's genius for intrigue and war – vastly increased their reach.

The 8 or 9 children in Eleanor and Henry's family eventually sparked a series of civil wars. Apparently fed up with Henry, Eleanor retired to Poitiers, where she cultivated a court to train leaders that reputably was unrivaled in its splendor and intellectual brilliance, all the while scheming against her husband. Their sons rebelled against Henry, who forgave them but imprisoned her until his death 13 years later.

At the same time, Henry laid the foundations for the supremacy of civil law in Britain over that of Catholic Rome and defended his territories with a ferocity that his sons, esp. Richard Coeur-de-Lion and John, adopted to keep their vassals in line; the 4 surviving brothers were bitter rivals, forever seeking treacherous alliances as they maneuvered for power and succession (the basic plot of A Lion in Winter). It is a fascinating case of family dysfunction with catastrophic consequences. After Henry died during the next rebellion, Eleanor, newly freed, consolidated power in the cauldron of feudal politics, alternating elaborate machinations of diplomacy, betrayal, and brute force.

That leaves Richard as King, who promptly disappeared for a decade on the 3rd Crusade, that great debacle. Weir seems to admire him and portrays him as a great if cruel war leader of singular potential. Upon his untimely death in the search for a nonexistent treasure in France, it was John's turn. Meanwhile, under King Philip Augustus, the Capets of France were resurgent, in spite of his weaknesses as a leader and thinker. Eleanor ended her life in uncertainty at 80 years of age, while John's murderous cruelty tainted his kingship (resulting in the Magna Carta), alienating his vassals and opening the way for the loss of virtually all of his French territory. The Plantagenets then rule for the next 300 years in Britain.

It was a remarkable life. Weir succeeds in bringing her to life with the caveat of how little we actually know about her as a person. The strongest part of the book is a case study of the feudal system.