Running a vast nomadic empire

Review of The Horde: How the Mongols Changed the World by Marie Favereau

Though many historians know better, the Mongols are traditionally portrayed as brutal conquerors and indiscriminate pillagers, for example with the sack of Bagdad – savage precursors to more refined sedentary nations. Marie Favereau sets out to prove this image wrong, that is, to demonstrate that the Mongols were particularly shrewd at building upon their culture, in the process creating a political system and civilization that were flexible and accommodating, co-opting what its many peoples had to offer. Hence their rule lasted centuries. Its immediate legacy was the first global trading system since the Roman Empire, a Pax Mongolica that influenced the states in formation from China to England. In the longer term, Favereau argues, it set an example that deeply influences us even today.

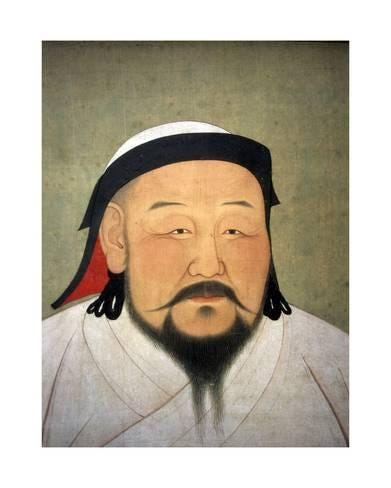

Favereau’s book focuses on the Horde in the north (the Jochin ulus), only a quarter of the loose Mongol Empire that Chinggis Khan divided among his four sons. Chinggis Khan’s immediate goal, she argues, was to unite the nomadic peoples of the massive steppe plain that ran from China to Hungary. Beyond keeping it together in a pragmatic manner, he did not have a grand vision for the society or political system he wanted to create, but did achieve a regime of sorts that functioned well and lastingly. Favereau takes us into the mechanics of a neglected one, the Jochin regime of the north.

Chinggis Khan’s Jochin grandson forged institutions in a sub-empire that were designed to bring the advantages of safety and economic growth to its subjects. While there was a clear hierarchy of power in the royal descendants of Chinggis Khan, who were the only ones eligible to gain the title of top leader or Khan, they were supported by a mix of aristocrats, nomadic leaders (the begs), and a military elite. Each potential top leader had a keshig, a kind of imperial guard of administrators, generals, the best fighters, and not least, diplomatic hostages who were brought up within the system from childhood. Membership in the keshig could be relatively fluid, incorporating new peoples as they joined the empire (usually by conquest, but also as willing vassals) to enhance its expertise and flexibility to operate in new territories and among new peoples. Each keshig functioned as a government in waiting, building the leader’s trust in a group of able administrators who were ready for action and sworn loyalists. So far as I know, this is a unique institution.

This regime served both to enhance the prestige of the royal lineage and to incorporate new peoples into the empire. Conquered peoples – and particularly their warriors – were invited to join the cause of the empire as military recruits and adjuncts. But it went farther than that, for the peoples were also dispersed into the wider Mongol society, marrying into families, working as partners in the economy, etc. As most of them were Steppe nomads, their culture often found a good fit within that of the Mongols due to similarities in their tradition and life style. In this way, over centuries, ethno-linguistic groups were absorbed and transformed, often losing their languages and tribal claims to the regime. In this way, the Kazaks, Uzbeks and many other peoples were born under the administration of the empire, often from a founding beg (whose name they took as their own).

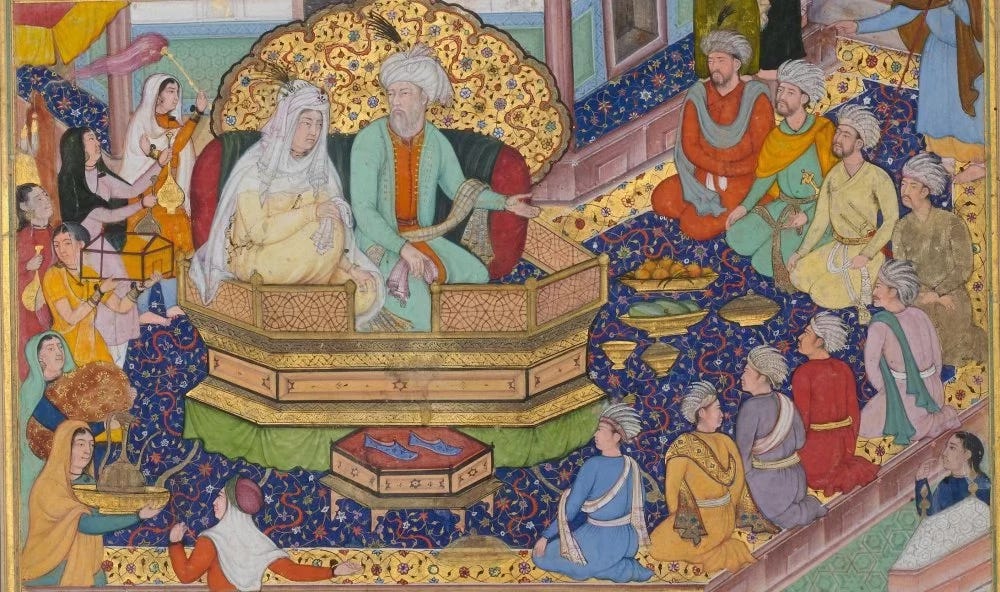

The keystone of the regime was the redistribution of spoils along with the fruits of economic growth. This occurred during regular, post-conquest meetings of the quriltai, a parliamentary-like gathering of aristocrats and begs whose vote lent legitimacy to the Khan. It is an interesting example of how traditional practices – the “ostentatious generosity” of the Steppe peoples – grew into a durable, even formal, institution. As such, the generation of wealth for redistribution was a principal goal of the regime, not just to enrich the elite, Favereau seeks to convince us, but to improve the lot of the entire society. Of course, this kept a check on greed and rapaciousness at the top; more importantly, it disciplined the entire society, keeping intact the productive assets of conquered and assimilated peoples via an inclusive system of government. If the system failed to generate wealth, the entire regime, intricately balanced and presumed effective, was threatened with collapse - if unpaid, the army suddenly could refuse to maintain order, opening the gate to chaos.

In terms of external relations, the Horde was often at war with its southern Mongol neighbors, the Ilkanids. The latter occupied lands in the middle east, adjacent to the Mamluks and Byzantium, with whom they fought or allied themselves according to their immediate advantage and needs. (As an aside, Favereau explains the destruction and sacking of Bagdad as the momentary and highly unusual result of a power dispute within the Ilkanid regime. In my opinion, this may be too generous an interpretation.) Eventually, the Jochin ulus triumphed over the Ilkanids, which gave them effective control of the northern silk roads, an enormous trade advantage that brought much of western Europe into their sphere of influence and trade.

The Jochid ulus also decisively shaped the medieval state of Russia, a series of principalities that operated semi-independently and traded extensively with the Mongols; in effect, they anointed the prince of Moscow as the head of the other Russian princes. This was a revelation to me as I had thought that the Mongols overcame the Russians and brutally occupied them – in fact, it was a civilized system of governance and the mixing of Mongol and European blood was voluntary and indeed a source of stability by aristocratic marriage.

The system eventually broke down first because of the Black Death and secondly, because the institutions that governed the passage of power lost their legitimacy. In effect, it had devolved into a military regime in which begs competed for supremacy. Its legacy was of a vast and effective nomadic empire, a regime that had functioned and adapted to changing circumstances for nearly 300 years by some reckonings.

As an academic treatment, The Horde can be a bit of a slog as a reading experience. While there are flashes of eloquence and insight, for the most part the prose is pedestrian. Many of the petty details of intrigue are included, which are of minimal interest. What comes through are the ideas and Favereau’s proofs, which I found convincing and stimulating enough to get me through the book.

Related:

Genghis Khan as enlightened and visionary

This book is an odd mix. On the one hand, it is supposed to be a kind of narrative based on new source materials, an intimate biography – an interesting story, with quirky personal details, the ascription of emotion at crucial moments, and some (surprisingly poor) evocative language. On the other hand, as an anthropologist and scientist but unmistakably…

Genghis Khan, Attila the Hun, and Tamerlane, Sword of Islam

When I was first studying Roman history, mysterious antagonists always came up: Scythians, Parthians, Huns, Alans, to name just a few. Who were they? Why did they attack constantly? They seemed to return without explanation from a void, with frightening strength and then, disappear. It was only much later that I realized they were warrior nomads from th…

Repressive regime as precursor to Soviet totalitarianism

Richard Pipes has a principal theme: in the area that became Russia, the land was extremely poor, which restricted economic possibilities and warped its society. His entire book is an application of this theme to the history of the Russian state: if akin to a survey history, it is intended to drive this point home.

The Eastern Rome that survived 1,000 years more than the West

“Byzantium” was an invention of the Enlightenment: it was taken to embody imperial cruelty, theocracy, bureaucratic fiat, and blatant injustice. According to Anthony Kaldellis, this was a caricature designed to contrast against the virtues of enlightened despots