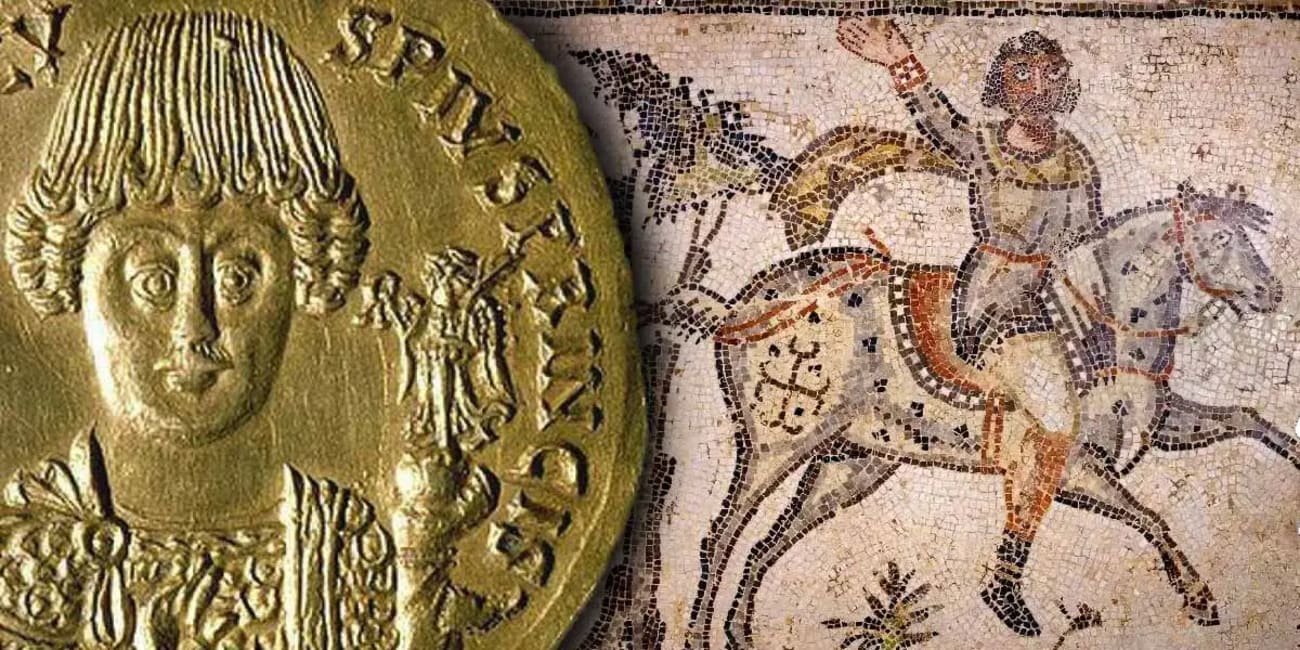

Genghis Khan, Attila the Hun, and Tamerlane, Sword of Islam

Review of Empires of the Steppes: A History of the Nomadic Tribes that Shaped Civilization by Kenneth W. Harl

When I was first studying Roman history, mysterious antagonists always came up: Scythians, Parthians, Huns, Alans, to name just a few. Who were they? Why did they attack constantly? They seemed to return without explanation from a void, with frightening strength and then, disappear. It was only much later that I realized they were warrior nomads from the Eurasian Steppes, an unimaginably immense grassland, a corridor stretching from northern China to Hungary. Nomad leaders included Genghis Khan, Tamerlane, and Attila. This book offers a systematic look at them, in dense historical context, at all of them in their astonishing variety and impact.

For their origins, Harl goes all the way back to the Proto-Indo-Europeans, the pastoralists that began to leave the Pontic-Caspian Steppe roughly in the Chalcolithic Age. They had domesticated and then bred the horse, developed incredible riding skills, and apparently later, established a martial tradition that would challenge the world. The horse was essential. With it, not only they could travel quickly and feed them on the Steppe grasses, but they could be used for incredibly effective fighting forces and even food. As their techniques developed, they included: uniquely powerful composite bows, saddles, spoke-wheeled vehicles (both chariots and wagons), riding trousers, and later, stirrups. This enabled the Indo-Europeans, in particular the Persic peoples as well as the Tocharians in the far east, to live as independent, widely ranging nomads; it was a lifestyle that many other peoples adopted once they understood the advantages in their methods, including the Altaic peoples, that is, the Gök Turks and Mongols.

With the agricultural revolution, sedentary civilization and then urbanization became ubiquitous. To nomads, Harl informs us, these settlements represented a source of products they needed on the Steppes, through trade or otherwise: foodstuffs, manufactured goods, cloth, gold, slaves. While not all nomads were warriors or brigands – indeed many scholars believe that the extraordinary expansion of the Indo-Europeans was largely peaceful until about 1,200 BCE – a number of aggressive clans and tribes emerged that would regularly attack rich settlements for booty, slaves, and sport. It was their way of life and their survival depended on their martial skills.

As large sedentary civilizations developed, warrior nomads organized themselves into larger fighting forces as well. With its dispersed trade networks and administrated economy, Rome was a particularly rich and vulnerable target. The Scythians and later the Parthians, both Persic peoples, attacked on Roman frontiers, quickly able to flee into the Steppe and rarely risking to fight the Romans en masse, in the large and decisive pitched battles to which they were accustomed – the enemy was frustratingly fluid, melting away as quickly as they could form attack columns. Organized as confederations, often multi-ethnic and -linguistic, the nomads also represented a very difficult foe with which to negotiate. Who could the Romans trust? What authority could nomad leaders wield, particularly over their distant confederates? China, India and other civilization faced similar problems with the Mongols, Xiongnu, Sogdians, and many other groups.

Aside from harassment, even highly successful nomad groupings tended fade away rather than become significant, long-term threats to the larger civilizations. Nomad empires tended to be based around a single, charismatic individual, a canny politician who could unite the factions into a quasi-national fighting force. Once removed from the scene, their descendants and generals tended to fall into ruinous battles of succession. In addition, as the empire expanded, it faced increasingly critical logistical challenges, often collapsing due to needs in matériel and manpower; due to their dependence on grasslands to feed their cavalries, their reach also had natural limits. At Attila’s sudden death in 453 CE, the fighting force of the Huns – a huge multi-ethnic coalition – disintegrated immediately into warring factions.

Of course, the great exception was Genghis Khan. He created an empire that lasted for several generations, largely because he established institutions, mastered logistics, and transmitted his ideas to 3 grandsons whose genius was at least equal to his own. As with all the nomad empires, the Mongols could be extremely cruel and bloodthirsty. Upon the death in battle of his favorite grandson (Mutugen) in 1221 CE, Genghis once ordered the annihilation in vengeance of every living thing in the valley of Bamyan. While this was a typical form of psychological warfare, many of the cities he destroyed never revived, leaving only ruins; the sack of Baghdad is one of history’s greatest humanitarian and cultural losses. Harl pays a great deal of attention to Kublai Khan (r. 1264-94), who created the Pax Mongolica, an unprecedented geographical area of free trade and safety; though it would collapse in the wake of the Black Death, it furnished a model for future policymakers.

Harl argues that the Steppe nomads decisively shaped the modern world. This is certainly true in a geo-political sense. The Huns did not conquer Rome, but they weakened the western portion of the empire just enough to give ascendency to the German tribes, leading to its collapse and the formation of the medieval states. For their part, the Mongols created the preconditions for the reunification of China, which had been fragmented into kingdoms for hundreds of years and would emerge again as a great empire. They also furnished a model of governance to Russia – the absolute power of the Tzar may be based on Khan as much as traditional, western forms of monarchy. The last great nomad empire builder and destroyer was Tamerlane, who conquered much of the Mongol Empire, only to have his kingdom disintegrate upon his death in 1405. Though Tamerlane never completely destroyed the Ottomans in Anatolia and the Moghuls in Egypt, he forced them to reorganize their armed forces in ways that extended their influence into the 19thCentury. Interestingly, Tamerlane’s death marked the end of the Steppe empires – their mounted warriors could not outrun muskets and cannons or counter the new sea powers that were extending trade and the reach of Renaissance imperialists.

This book is a wonderful reading experience. If the reader is familiar with the general historical outlines of the great sedentary civilizations – Rome/Byzantium, China, Islam, and India – the stories of the Steppe-nomad empires fill a crucial, largely unexplained gap in many histories. Though I knew about the Steppe nomad warriors, I had never thought of them as a coherent force or a sociological phenomenon. It offers a unique vantage point, a perspective I have sought since college. Harl’s writing style is also great fun: he offers up tidbits of analytical information in extremely dense narratives. It is a masterpiece of academic rigor yet written in an accessible format.

Related reviews:

A wonderful intellectual adventure in archaeology and linguistics

Though this is a book that advances a highly complex set of academic arguments – that the spread of proto-indo-european languages was not accomplished by violence, that linguistic methods can supplement the physical evidence to pinpoint its origins and fundamental splits – it is also highly readable for interested laymen. I myself cannot judge his ideas…

Absolutely first rate historical inquiry

Heather begins with a description of the Empire as it stood about 300 CE. Rome itself had become a religious and ceremonial capital, far from the frontier, where the real political power had migrated to serve military necessity. It was a vast and integrated world, unified not just by military power, economic activity, and the most advanced administrativ…

How to run a vast nomadic empire

Though many historians know better, the Mongols are traditionally portrayed as brutal pillagers and indiscriminate conquerors, for example with the sack of Bagdad – savage precursors to more refined sedentary nations. Marie Favereau sets out to prove this image wrong, i.e. to show that the Mongols were particularly shrewd at building upon their culture,…

Repressive regime as precursor to Soviet totalitarianism

Richard Pipes has a principal theme: in the area that became Russia, the land was extremely poor, which restricted economic possibilities and warped its society. His entire book is an application of this theme to the history of the Russian state: if akin to a survey history, it is designed to drive this point home.