Is capitalism terminally ill?

Review of How will Capitalism End? Essays on a Failing System by Wolfgang Streeck

Wolfgang Streeck examines capitalism as a social phenomenon, as part of a society we are constructing. Acknowledging that capitalism may be too complex to quantify in the usual numbers game, he chooses to return to the roots of classical economics, which was as much a branch of moral philosophy as it was an analysis of the earliest phases of the industrial revolution. Streeck’s book offers a take on the health of late-modern capitalism, arguing that it is in the terminal phase of illness. If abstruse and difficult to read, at its best his book is an intellectual adventure and extremely useful – I see a number of things more clearly, even as I remain skeptical regarding some of his conclusions.

Streeck defines capitalism as a “complex system” tending to disequilibrium: it must balance technology, production, and power (or ownership) to resolve the crises that these inevitably generate as they interact. So far, he observes, capitalism has been able to emerge from crises for brief periods of prosperity and stability, in which the legitimacy of the system is re-established and reinforced – in effect, its indisputable dynamism has been able to convince the public that “private vice can be converted to public virtue”. However, with the tendency of the owning class to accumulate power and technology to introduce disruptive innovations, this stability is regularly subverted and economic crisis ensues.

At this moment, he argues, the capitalist system is at grave risk of disintegrating, not in a typical crisis-and-renewal cycle, but under the weight of the worst conjunction of factors it has yet seen. It should be noted that this is not by any means a Marxist analysis, the deficiencies of which Streeck is at pains to point out.

The symptoms of this incipient crisis include: chronic low growth; worsening inequality; rising debt; the “neutralization of post-war capitalism’s progress engine” via legalistic fiat; a weakening of both regulation and the political guidance of economic life; oligarchic powers enhancing their ability to impose a kind of “neo-feudal” control on society; globalization demolishing national controls of markets, thereby promoting the commodification of labor, land, and money; growing corruption. Add to that a pervasive demoralization that foments disorder and inspires populist demagogues, and you have a system on the verge of decisive collapse, in which one factor could tip the boulder to fall down the mountain into global anarchy. This is, in my opinion, a terrifying scenario that is indeed plausible.

Finally, we are suffering from a complete lack of political vision as to what should do to avert or remedy this, i.e., Marxism, neoliberalism and all our other current “-isms” offer no realistic roadmap or solutions. This last point, I am convinced, is particularly salient today, when our policy prescriptions seem as exhausted as the ideologies of our political parties. This makes Streeck’s perspective of the greatest value, particularly as he places it in an over-arching logical context.

Streeck presents a vivid “image” of the end of capitalism, not as a prediction of outcomes, he emphasizes - cannot know what form things will take in the aftermath. What he presents are the underlying dynamics.

The problems start with a social system in “chronic disrepair”, an underfunded safety net and deteriorating infrastructure, with the economy mired in slow growth, inequality, etc. Meanwhile, public goods are being “privatized”, which opens them to plundering and simple deterioration from lack of funding.

Compounding these problems, a new regime of regulation and policy space for legitimate governmental action cannot be agreed upon or even conceived. Instead, demagogues seek scapegoats to blame, their political theatre crowding out realistic proposals. Beyond the tendentious promises of neoliberalism, there is no strategic political vision.

Moveover, governments are losing the ability to implement economics policies. With the role of the US as the world’s banker and guarantor of currency stability receding, the global financial system is fragile and inexorably fragmenting. Finally, in surrendering their sovereignty to international organizations or central bankers, many national governments are forfeiting their ability to formulate their own economic policies, instead relying on neoliberal precepts, labeled the “free market”.

As these problems accumulate, the economy and society become dysfunctional, leaving them increasingly vulnerable to disruptions and unintended consequences that could suddenly threaten the survival of the entire system.

Eventually, Streeck argues, the system will lose its political legitimacy, which opens the way to complete collapse and the unknown system (or lack of one) that would follow. “Capitalism,” he writes, “as a social order held together by the promise of boundless collective progress, is in critical condition.”

The underlying causes of this situation, he observes, can be seen in post-war economic history 1945-79 represented the era of democratic capitalism, the stability and growth of which continue to dominate the expectations and conceptions of policymakers. The balance that had been struck consisted of several elements: the fruits of solid growth – from war reconstruction and the growth of the automobile-dominated economy – were shared by labor and management; as such, unions moderated their demands as they accepted the logic of capitalist markets. Of decisive importance, a number of fundamental inventions were coming to fruition in the automobile, but also in the establishment of a modern infrastructure (highways to suburbia, water purification, etc.) as well as the white-good conveniences (think washing machines) of the mass-consumer economy.

All of this was easier when the economic pie was expanding for everyone into the late 1960s, the moment that growth (as a function of demand for products and basic services) permanently slowed, in large part because two cars per family was enough. Soon, a “distributional conflict” arose between owners of capital and workers: both demanded a larger share of the fruits of production, only this time, they were fighting over static “slices” rather than an expanding pie. At first, policymakers allowed inflation to distribute wealth by default – it was the creditors and investors who immediately lost out, but this soon became unsustainable as inflation damaged the economy for everyone. This was the time of “stagflation”.

The neoliberal policy phase began in 1979, when Volcker (the Jimmy Carter-appointed Chair of the Federal Reserve Bank) raised interest rates in order to choke off inflation. Unemployment increased to hitherto unacceptable levels and we have never returned to pre-1973 prosperity; this weakened union leverage in wage demands as well as increased the popularity of the tax cuts, leading to the supply-side economics of President Ronald Reagan. His tax cuts were sold in the 1980 election as a painless solution that would take care of itself - the market would replace active political guidance as the “objective” arbiter of the economy.

According to the supply-side theory, the Reagan tax cuts were supposed to generate such robust economic growth that tax receipts at some future date would increase without the need for budget cuts, thereby making up for the loss of government tax revenues. But they didn’t. As we now know, the result was chronic, massive deficits. To continue to provide the government services that remained popular and needed, the Federal Government began to take on unprecedented levels of peacetime public debt. This did not, as conservative ideologues feared, “crowd out” private investment. Indeed, because the dollar was the international reserve currency, the US was able to maintain its mounting trade deficits by creating money – unlike all other countries that had to pay in US dollars. In Streeck’s scenario, this initiated an era of private debt (1979-2008), in which consumers took on ever larger personal debt in order to maintain living standards.

Paradoxically, by deregulating banks and severely cutting back government services, the left-leaning Clinton Administration only deepened neoliberal economic policies. For their part, corporations gained easy access to cash as the complexity and variety of financial instruments proliferated, which helped to fuel an asset bubble along with foreign investment in US Treasury Bonds. Furthermore, with unions in decline and shrinking employment options, the regulatory checks on corporations were gradually removed as “impediments to growth”, a trend which accelerated during the presidency of George W. Bush.

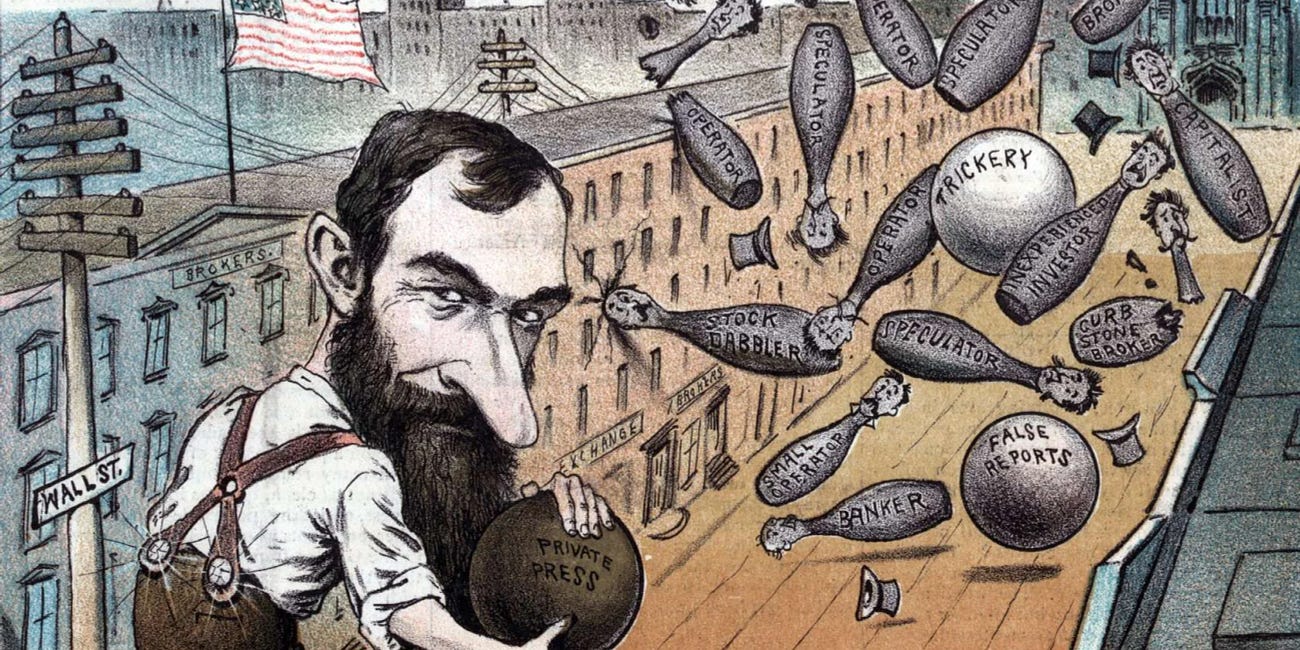

Home ownership, Streeck asserts, allowed some lucky consumers to “participate in the speculative craze”. The result was a pyramid of debt-dependent “paper wealth”, though many were simply using credit cards to prop up eroding living standards. While the computer industry, the internet, and the financialization of economic activity (“paper entrepreneurialism” in Robert Reich’s unforgettable phrasing) generated growth for the lucky few at the top, it did not filter down to the middle class, creating inequalities in wealth unseen since the Gilded Age. In a related development, globalization subordinated national markets and political control to the larger inter-governmental and international institutions (EU, IMF, Multi-National Corporations, etc.), undermining the ability of governments to manage their domestic economies.

In 2008, the debt pyramid collapsed – too many financial instruments had been created for questionable endeavors, major “too big to fail” institutions were existentially endangered by bankruptcy – and so governments were forced to step in. Thus we entered, Streeck says, the era of sovereign debt, in which Central Banks, on behalf of nation-states, began to “socialize bad loans” into massive consolidation packages, essentially propping up the private sector at public expense. Throughout this crisis, the finance industry was not just saved, but generated extraordinary profits for itself, again only feebly spreading the wealth downward. Though the book only covers the situation to 2015, its analysis is exacting and highly accurate in my opinion.

That being said, no one can say how things are going to play out. I remember the Latin American Debt crisis of the early 1980s, an indescribably massive interlocking of government and private debt in a number of insolvent economies south of the US - the situation was so dire that many feared a global banking implosion. Forunately, in what was deemed impossible at the time, this crisis was solved by restructuring the debt and eventually, the economies themselves. Though I am not optimistic we can repeat this success (which nearly everyone has forgotten), it is at least possible we will come together and find a new way forward. Capitalism, for all its painful upheavals, has proved pretty resilient. I have more hope than Streeck.

While I found Streeck’s ideas invaluable to my understanding of capitalism today, there are a number of weaknesses in the book. It is cobbled together from previously written articles, perhaps edited somewhat to fit the book format, but as a read it is disjointed and concepts that go together are often presented in brief fragments that must be ferreted out at great effort. I had to read it twice. In addition, about 1/3 of the book are essays that are tacked on are not clearly relevant to the principal subject.

For example, much of the economic analysis is about Europe and the EU, which will interest only a portion of readers. To demonstrate the “impossible dream” of the Euro, Streeck goes into a lengthy analysis of the difference between southern EU states (domestic demand-based economies) and northern ones (export-based economies). To deal with chronic trade imbalances, the southern EU states needed to make periodic readjustments to currency value that the Euro rendered impossible, hence unworkable in the long run. Because northern states wanted a stable currency without inflation, their remedy was to impose austerity on the southern EU states, which became a genuine threat to the EU’s existence – with the Euro, only one orientation can dominate, each of which impacts the other negatively.

Though the book is uneven and rather difficult to read, I recommend that interested readers make the effort. The concepts are must-reads for specialists. Having lived in Europe during the rollout of the Euro and into the subsequent Greek austerity crisis, I now see what happened with far greater clarity. Of course, not every general reader would desire or need to understand this. I would estimate the book is at high undergraduate or graduate level.

Related review:

How government engineers the development and function of capitalism

If you want to get an historical grounding in the American economy and politics, this is the best book I know. The issues are clear from the beginning: how can we explain the explosive economic growth of the last few centuries? Why are depressions – panics, liquidity traps, and the like – apparently inevitable? What impact do government policies have? F…