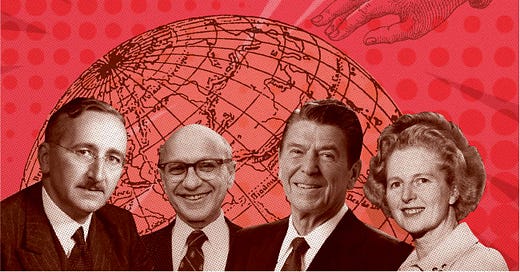

A polemic against Neoliberalism, but solidly backed by evidence and historical context

Review of Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea by Mark Blyth

In political economy, there are 2 principal lines of reasoning: the state should not intervene in the "free market" or it should. The difference between them is ideological, sentimental, and of great consequence. In this brilliant book, Blyth cuts through the rhetoric and makes the case that austerity – letting the market punish those who "violate the r…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Crawdaddy’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.