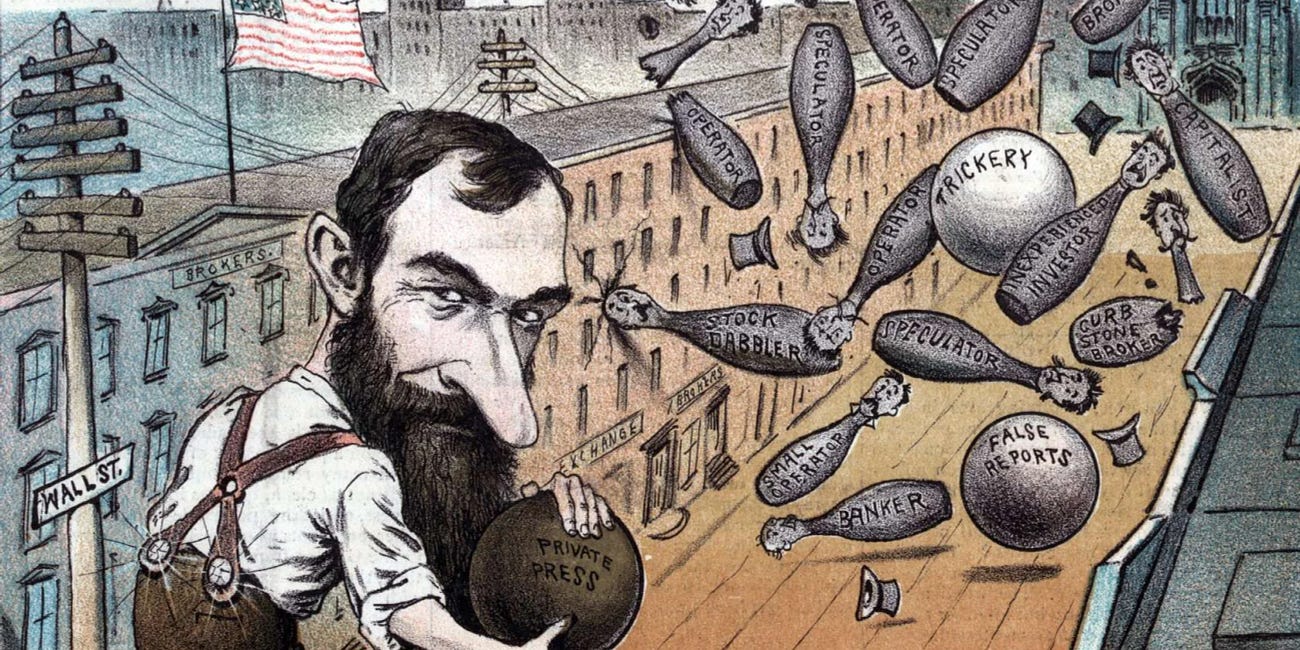

Capitalism as part of the enclosure movement

Review of The Origin of Capitalism: A Longer View by Ellen Wood

Capitalism has been portrayed as the optimal economic system for efficiency, opportunity and individual choice, a kind of freedom that best syncs with “human nature”, enhancing productivity and profits in a way that benefits everyone. Today, this had become an ideology, neoliberalism, which regards the market as a quasi-religious force that should be left to operate on its own. In looking at its origins, Ellen Wood argues instead that the costs of establishing capitalism as a system involve compulsion, disenfranchisement, even an anti-democratic impulse. The state was also a crucial actor.

The first third of Wood’s book is a rather turgid review of the way both scholars and revolutionaries viewed capitalism’s origins. There is the “classic commercialization model”, according to which capitalism has always existed in man’s character: given the chance, everyone would naturally trade, seek profit, and work to improve their situation. In other words, it’s human nature: essential, necessary, unavoidable. The only requirement for it to emerge is that the “artificial barriers” (feudalism, aristocratic privilege, government regulation, what have you) be removed.

In contrast, Karl Polanyi argued that a “market society” had to grow out of a static economy, in which “kinship sharing” had been balanced by “surplus extraction” for the aristocracy. The static system resulted in a subsistence economy for the many and a lavish life style for those few at the top of the hierarchy. For the majority of post-hunter-gatherer human history, this has indeed been the case. Developing the market society entailed industrial technologies, urbanization, and the commodification of inputs (natural resources, labor) that went on sale in “free markets”. In the process, the protections and rights inherent in the feudal system were lost, that is, access to the agricultural “commons” and traditional rights of land tenure were replaced by fenced-in private property belonging to an elite - historians call this the “enclosure movement”.

Furthermore, there is the “exploitation view” of early capitalism (roughly from the 17th century) that required slavery as an antecedent. This questioned the commonly presumed superiority of European civilization in technology and organization, depending as it did on slavery, imperialism and colonies in the accumulation of capital for investment. The emphasis is on international trade, in particular the slavery triangle, in which manufactured goods were taken to Africa in exchange for slaves, then slaves were traded for sugar and cotton in the new world, which helped to furnish the raw materials for manufacturing in Europe as well as the profits for investment.

Finally, in critiquing industrial organization, Marx focused on “capitalist imperatives”: competition, profit maximization, the compulsion to reinvest surpluses, the continual improvement of labor productivity and manufacturing technologies. Here, the emphasis was also on exploitation, this time of the proletariat by the capitalists. While there were questions regarding the precise source of this impetus (i.e. external pressures, rise of the bourgeois, etc.), this more or less completed the description of the capitalist concept as a system.

In the remaining 2/3 of the book, Wood offers her own explanation. Though an extended academic proof, it is far more engaging and original than the preliminary review, if occasionally repetitive. Profit-seeking actors of the feudal past, she observes, did not represent embryonic capitalists because they were involved in extractive activities, largely as rentiers. Traders, for example in the medieval markets of the Champagne Fairs (12th – 13th centuries), sought to exploit disadvantages between fragmented markets and did not invest to enhance productive capacities. To function, early markets heavily relied on extra-economic strength, including military superiority, shipping fleets (or navies for pirate mercantilism), infrastructure such as canals and railroads, as well as slaves and serfs, all of which required heavy state involvement (the “good princes”). Even commercially successful, urbanized mini-states, such as Florence and the Dutch Republic, failed to make the transition to a capitalist system.

The key, she argues, was the establishment of agrarian capitalism in 16th century England. This was the time of the enclosure movement, according to which aristocrats and gentry closed commons areas that had been available to peasants for centuries. On the one hand, direct agricultural producers were gradually disenfranchised – they lost their traditional feudal rights to their land and had to sell their labor for a wage in the market. Nonetheless, freed from serfdom, they could migrate and seek the best situation for themselves elsewhere. On the other hand, landlords operated under new rules of competition, requiring capital accumulation (profit for investment) and the never-ending search for ways to improve productivity. They had no choice but to submit themselves to this discipline or perish.

Meanwhile, the English state was fairly unified: there were fewer feudal remnants threatening its authority than in other countries, it had a coherent legal system and a good infrastructure; the capitalist gentry could operate in safety, in particular under state protection from peasant uprisings. These represented the necessary preconditions for the establishment of a free and genuinely functioning market in which these early capitalists could compete. The growing bourgeois class did not threaten revolution against the state, but sought to participate in its society. In contrast to rent-seeking aristocracies, it was a dynamic system in constant flux. It resulted, Wood says, in singularly productive farming.

Meanwhile, the growing ranks of the disenfranchised settled in cities. There, they had to find jobs. Many became sailors in the British Navy, which enabled the Empire to grow and function. Others entered nascent industrial organizations. By doing so, they became a mass market for affordable consumers goods. In Keynesian vocabulary, they increased aggregate demand for manufactured products from industry, hence they represented self-reinforcing investment opportunities that would further enhance the profits of entrepreneurs. This is the so-called capitalist virtuous circle.

As the first industrialized nation, this system enriched Britain to such an extent that it could impose it on other countries, which found themselves under compulsion to compete on the terms devised by Britain. Much of this required direct intervention by the state, which created opportunities for and supported industrial development; the state also sought to correct the inevitable imbalances that arose (depressions, the need for welfare protections, etc.) with the institutional powers at its disposal. In other words, the system became self-reproducing on a global scale and grew symbiotically with the modern nation-state.

Locke and others provided a convenient ideology to justify the system, according to which entrepreneurs gained rights to the land because they “added value” to it in the form of profit; this became one of the key justifications for imperialism and colonization. For example, because Amerindians did not “profit” from the land, they had no right to keep it even though they had lived off it for millenia. This was called natural law – unimproved land was a “waste” – and it became standard practice to destroy the traditional protections and rights that served peasant and hunter-gatherer populations in most of the colonies that were established into the 19th century.

Beyond illuminating the elements of early capitalism, Wood convincingly argues that the system itself does not represent a flowering of innate human nature, but was imposed on the world by coercive means. Its development was enabled and maintained by the state. Today, in order to survive, it remains a compulsion for states to intervene on its behalf.

This really got me to think and I see many things more clearly. That being said, the precise details of Wood’s historical argument must be argued out by academic specialists – I have no idea if said origin was in fact agrarian or the extent to which human nature is capitalist or not. Even if you don’t agree with her general conclusions or feel skeptical, the book is a wonderful exercise in thought, an intellectual adventure worth the effort.

Related reviews:

brilliant, yet abstruse argument on the misconceptions of classical economics

This is a classic critique of capitalism in historical perspective. While the ideas can be extremely interesting, it requires great effort. Nonetheless, I think that most of the arguments are sound, even though the predictions at the end of the book - of the imminent demise of market capitalism –proved premature.

The Gothic economy

The subject – how the world economy and trade system worked in the 13th and early 14th centuries – might not sound exciting, but for anyone interested in history, this is an essential read. This was the time of an economic and technological boom without precedent, in which Kubilai Khan, various European princes, and many others were able to interact and…

How the proletariat and slaves made global capitalism and invented universal human rights

Though this book is a bit of a jumble, it is an attempt to cover those normally invisible to history, at least as agents of change: slaves, sailors, and the proletariat at the birth of capitalism as well as the revolutionary era. They are the “motley crew” that form the heads of the hydra in the title.

How government engineers the development and function of capitalism

If you want to get an historical grounding in the American economy and politics, this is the best book I know. The issues are clear from the beginning: how can we explain the explosive economic growth of the last few centuries? Why are depressions – panics, liquidity traps, and the like – apparently inevitable? What impact do government policies have? F…