The Gothic economy

Review of Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250-1350 by Janet Abu-Lughod

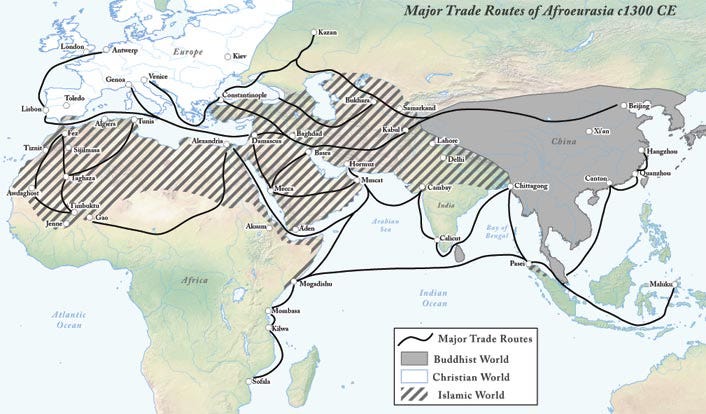

The subject – how the world economy and trade system worked in the 13th and early 14th centuries – might not sound exciting, but for anyone interested in history, this is an essential read. This was the time of an economic and technological boom without precedent, in which Kubilai Khan, various European princes, and many others were able to interact and exchange goods and ideas in relative peace. It is a golden era before a global collapse that ranks with the fall of the Roman Empire or the Bronze Age, due a combination of plague, climate change, and political chaos. The scope is breathtaking, the writing elegant if austere, and the concepts fundamental to understanding political economy.

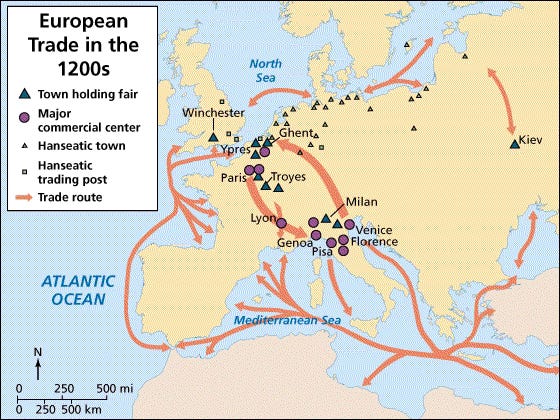

In Europe, truly global trade first sprang up around the Champagne fairs. They arose from a combination of independent, trade-oriented princes, who offered safe conduct and rule of law to merchants who traveled from far away to participate; similarly developed adjacent economies that encouraged sophisticated demand (e.g. trade in unique resources like English wool to fuel textile industries in Flanders); and convenience of access as based on transportation technologies, which were later displaced by the development of riverain and oceanic means to Bruges and Ghent.

In their turn, the Flanders markets flourished for a time, but lost their control with the rise of Italian corporations that were part of the state and hence quickly declined into dependencies.

This opened the way to Venice and Genoa, states that developed a kind of proto-capitalism, whereby capital could be raised for investment by a pool of individuals that went beyond the capacity for states or sovereigns to do so; these "capitalists" were able to seek profit with less interference from the state and, through sea transport, find the best protected venues for their exchanges. Abu-Lughod calls these states "compradorial", in that the state supported independent private action via military backing. This time also saw the rise of specialized, near-industrial niches (they still relied on muscle and water power), such as the textile manufacturers of Flanders, that became sources of great wealth accumulation, the fruits of which are still on display in their beautiful cities. Finally, new jobs began to emerge, i.e. the independent commercial shipper.

This dynamism was challenged not just by the Black Death plague, but by the geopolitical rivalry that pitted Venice against Genoa in a series of costly wars. Poor harvests also contributed to the collapse as temperatures fell in a mini-Ice Age.

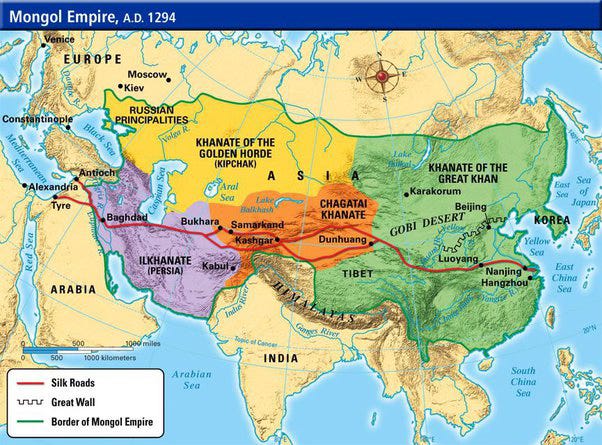

With the Mongol Empire in the Near and Far East, Kubilai Khan established a vast zone of unprecedented safety, which hugely reduced transport costs for trading purposes and stimulated the growth of an integrated economy. However, there were several weaknesses that caused the empire to split up into warring factions. First, depending on the skills of others, the Mongols remained essentially parasitic and the burden of maintaining their state alienated subject peoples. Second, as with all empires, the Mongols remained dependent on continual geographic expansion to secure booty and resources; their system never quite stabilized or consolidated itself. Third, networks and interactions over such a huge terrain left them highly vulnerable to the Black Death.

The Gulf states, Egypt, and kingdoms in India vied at various times for economic influence, thought were unsustainable because they were based more on their locations than any technological or political advantages. China was something of a unique case – it did well when both the land and sea routes were open, combined with its industries (based on technologies, such as unequaled porcelain manufactures), commercial acumen, and a supportive, if tributary, bureaucratic system.

This book is a wonderful intellectual adventure. It never falls into tropes, such as advocating free-market fundamentalism or private property as the sine qua non of successful economic activity, but sees economic development in context, with the participation of the state or political authorities as active supporters of private traders and industrialists. It is also very fun to read and never dryly academic.