If ever there was a crisis that defines an age, the Chernobyl nuclear disaster is it. Not only does it include technological complexities and science, but the way it rolled out is an indictment of the Soviet system and Gorbachev's inability to change it without destroying it. There are also vivid personal histories of ruined lives amidst heroism, cowardice, and defiant stupidity. Higginbotham's book is a riveting reading experience and is indispensable to understanding the modern industrial age.

Higginbotham begins with the Soviet system itself and its deadly mix of ideological fanaticism, propaganda, and the compromises that normal citizens had had to make to survive. Driven by the necessity to prove its superiority over capitalism, Soviet apparatchiks created a vast network of lies and half-truths: to meet impossible goals imposed from above, those lower down inflated their accomplishments, hid failures, and cut corners as they passed information up the chain to deluded leaders. In the case of the nuclear power industry, this resulted in fatally flawed designs, willful ignorance of its dangers and numerous near-catastrophes, with arrogant fools in positions in authority. The KGB served as the much-feared enforcers of all this.

Then there is the technology. Higginbotham covers it in both separate chapters and in bits interwoven into the narrative, reminding the reader of the details. This topic can be rough going. In a nutshell, I believe that the crucial flaw was that the control rods in the reactor – which absorb neutrons, slowing or stopping the nuclear reaction when inserted – would momentarily increase reactivity due to their composition. In addition, as the reactor was graphite-based, under certain conditions (low water levels), it created a positive feedback loop rather than serve as a natural dampener during power surges. Finally, given the slapdash construction – a necessity under the pressure to produce gigantic facilities as a showcase to the world without the required equipment – Soviet reactors were prone to breakdowns; their technology was shoddy, outdated, and brittle. The result was an extremely fragile construction that required hyper-vigilant operation, in which thousands of valves had to be maintained at the right levels, all without understanding the hidden dangers of the design flaws.

The human factor is crucial. Beyond the mediocre apparatchiks, many of the engineers running the plant were completely unaware of the shortcomings of the graphite reactors, often poorly trained and lackadaisical in their oversight, with the competent technicians badly overworked. It was thus an accident waiting to happen, inevitable as Higginbotham sees it.

Higginbotham weaves a wonderfully compelling narrative. On April 25, 1986, the meltdown is covered in such frightening detail that is worth the price of admission – during a long-delayed test under unusual circumstances, the temperature of the reactor core spiked in a split second, melting it and then exploding into the atmosphere, whence it poisoned vast swaths of Europe. This evoked my childhood fears about "radiation" – now I know how it unfolded in real life. Higginbotham's descriptions of those poisoned will make your blood run cold, moreso in that it was so arbitrary, a matter of where you stood at the wrong time, even within the same room. Moreover, he explains how the fire was put out, the many instances where even worse catastrophe was barely avoided (e.g. an environmental breach into the water table), and the aftermath of cleanup, containment, and the many uncertainties that remain.

At the center of the crisis is Victor Brukhanov, an ambitious engineer who has to build the 4 reactors clustered near Chernobyl as well as the elite town to house the workers, Pripyat. We follow the course of his career as he morphs from a conscientious idealist, whose concerns ranged from safety to the aesthetic and conveniences of the town, into a seasoned apparatchik operating within a corrupted and deceitful system. In the space of a week, he is demoted from hero status to scapegoat, winding up in prison. There are scores of other participants, many of them heroic, many doomed to die horrifically from radiation sickness, many disillusioned by the roles they are forced to play. For his part, Gorbachev comes off as concerned but impotent, a well meaning man out of his depth and both baffled and obstructed by a dysfunctional system.

This is really great reading. Perhaps there are better treatments, but I view this book as the ideal place to start. The HBO mini-series is a great story and was based on this book.

Related reviews:

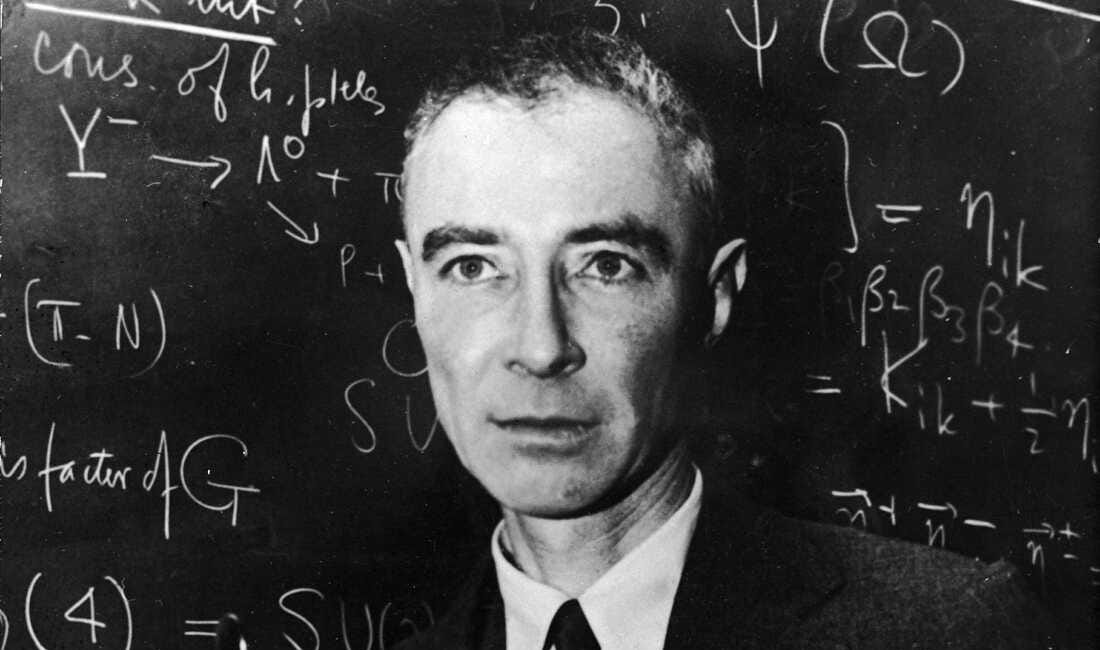

Celebrity intellectual, doer, and political martyr

It is rare to read a biography so rich in detail, so clear in ideas, and so beautifully written that it can be counted as literature. Oppenheimer is a unique figure in American history: starting as an academic, he became a master administrator for one of the most important technological breakthroughs in the history of mankind – harnessing the atom – and…

Good, dry scholarship

This biography fills a significant gap in the historical record: behind the incredible scientific and engineering triumph of the Manhattan Project, there was a master administrator. Leslie Groves was that administrator, the take-charge guy who knew how to inspire, find competent people to whom he delegated tasks, cajole and bully his way into the histor…

Definitive history of the Manhattan Project, from the basic science to detonation

This is one of those books that has it all: fascinating personalities, fundamental scientific discoveries explained with clarity, and the birth of political issues that are as relevant today as they were 60 years ago. That it is almost certainly the best book on the development of the atomic bomb is in itself remarkable, as the field is already crowded …