Celebrity intellectual, doer, and political martyr

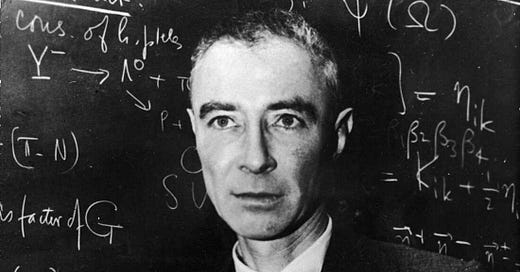

Review of American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin

It is rare to read a biography so rich in detail, so clear in ideas, and so beautifully written that it can be counted as literature. Oppenheimer is a unique figure in American history: starting as an academic, he became a master administrator for one of the most important technological breakthroughs in the history of mankind – harnessing the atom – and…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Crawdaddy’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.