600 pages on a guy who had one good idea

Review of The One Best Way: Frederick Winslow Taylor and the Enigma of Efficiency By Robert Kanigel

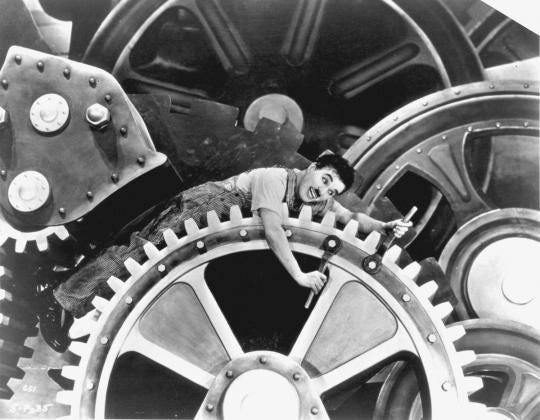

For anyone who has worked – on an assembly line, as a bureaucrat-in-a-box – the greatest workplace nemesis is a nonexistent ideal: the theoretical person against whom your “efficiency” is measured. Often, not even a boss or office rival is as irritating as this standard, the product of stopwatch-wielding efficiency experts and industrial psychologists who claim to have a scientific measure of “average output.” In The One Best Way, science writer Robert Kanigel examines the first so-called efficiency expert of them all: Frederick Taylor, the turn-of-the-century engineer and pioneering management consultant.

Taylor's idea was simple: break down all jobs into their smallest component tasks, experiment to determine the best way to accomplish them and how fast they can be performed, and then find the right workers to do them. It was called scientific management, or “Taylorism” – a formula to maximize the productivity of industrial workers. “The coming of Taylorism,” Kanigel writes, took “currents of thought drifting through his own time – standards, order, production, regularity, efficiency – and codif[ied] them into a system that defines our age.”

Though he had an enormous impact on our everyday lives, today Taylor is little known outside management circles. This is curious: in his own time, Taylor was a world-class celebrity, almost a prophet, advocating an organizational revolution that would link harder work to higher wages – as well as instituting shorter working hours and regular “cigarette breaks.” His books and articles were translated into all the major languages and passionately studied, even in the Soviet Union, as guides to a future industrial utopia; he was, in many ways, Stalin's expert. Yet Taylor was also reviled as a slave driver who devalued skilled labor and despised the common worker. Indeed, he was ridiculed as a failure in many of his business undertakings.

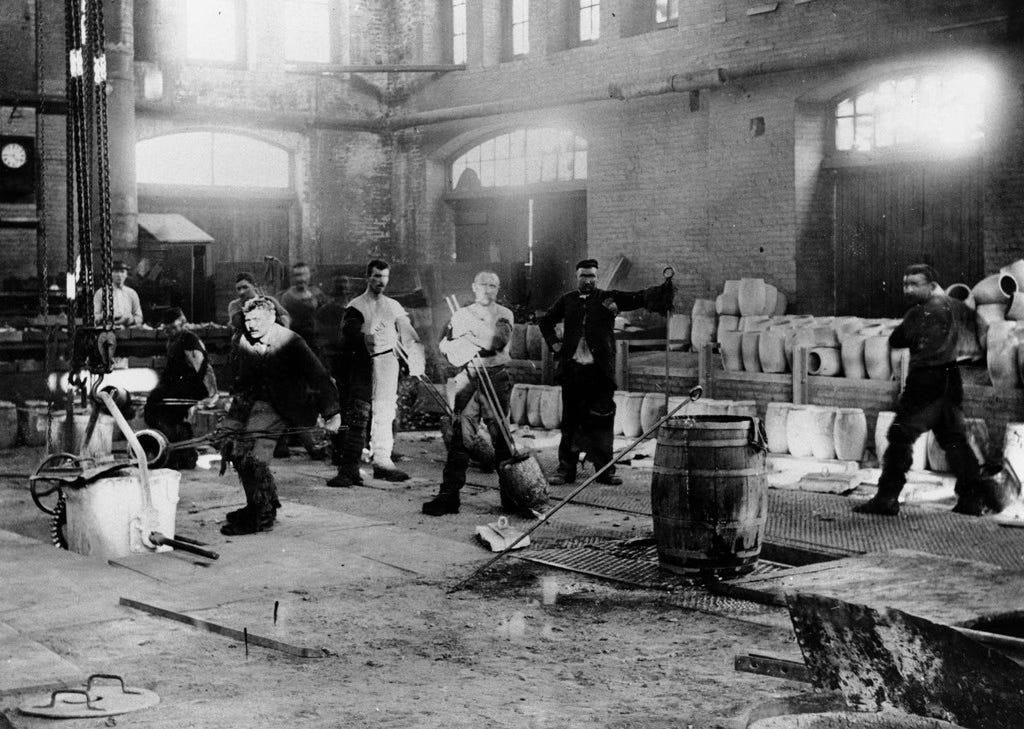

Much of Kanigel's book is devoted to descriptions of the shops that Taylor worked in: a ball-bearing factory, a paper mill, and machine-tool plants, to name a few. It's dramatic how different the world he describes is from the work environment of today. In his time, there were no highly educated managers attempting to exercise minute control over relatively unskilled employees. Instead, craftsmen dominated those oily pits – spinning steel-cutting lathes, constructing elaborate sand molds for machine tools, and maintaining the gigantic leather belts that harnessed the energy of central steam engines. This was in many ways the most fascinating part of the book for me: I learned what people did in the decaying mills that surrounded my New England home.

To all but the most practiced eye, such a workplace was a chaotic scene. What the craftsmen did – and what they were capable of – was to a large degree a mystery to management, which deprived the managers of control and power, leading to a number of stunningly counterproductive practices. If tool and die makers produced jigs beyond a certain threshold, for example, 19th-century foremen would dock (!) their pay per item – an obvious incentive for them to slow down. And because ball-bearing inspectors in a Fitchburg, Massachusetts mill worked slowly and talked too much, they were forced to put in 10.5-hour days, without breaks.

Taylor witnessed such practices and decided he could do better. In one of his most famous experiments, on “Schmidt”, he got a common laborer to triple the number of bars of pig iron he transported down a plank each day. All he did was pay the man more, linking higher output directly to higher wages – hardly a revolutionary thought today. His solution for the gossipy ball-bearing inspectors was to separate them, shorten their working hours, increase their pay, and allow them to relax together occasionally; in return, they were expected to work harder, and they did.

Once Kanigel establishes that Taylor's method worked well (to a certain extent), the book becomes tough going. Despite his elegant prose, Kanigel's exhaustive treatment of his subject's life and experiments strained my interest. Do we really need to know in exhausting detail, for example, how Taylor once spent months alternating the size of coal shovels in the name of furnace-stoking efficiency? Or the entire list of his vacation companions for one summer on a cruise ship? Such biographical detail can add spice to a compelling narrative, but to include them only as an exercise in thoroughness, as Kanigel does, is tiring. Taylor simply is not interesting as a personality.

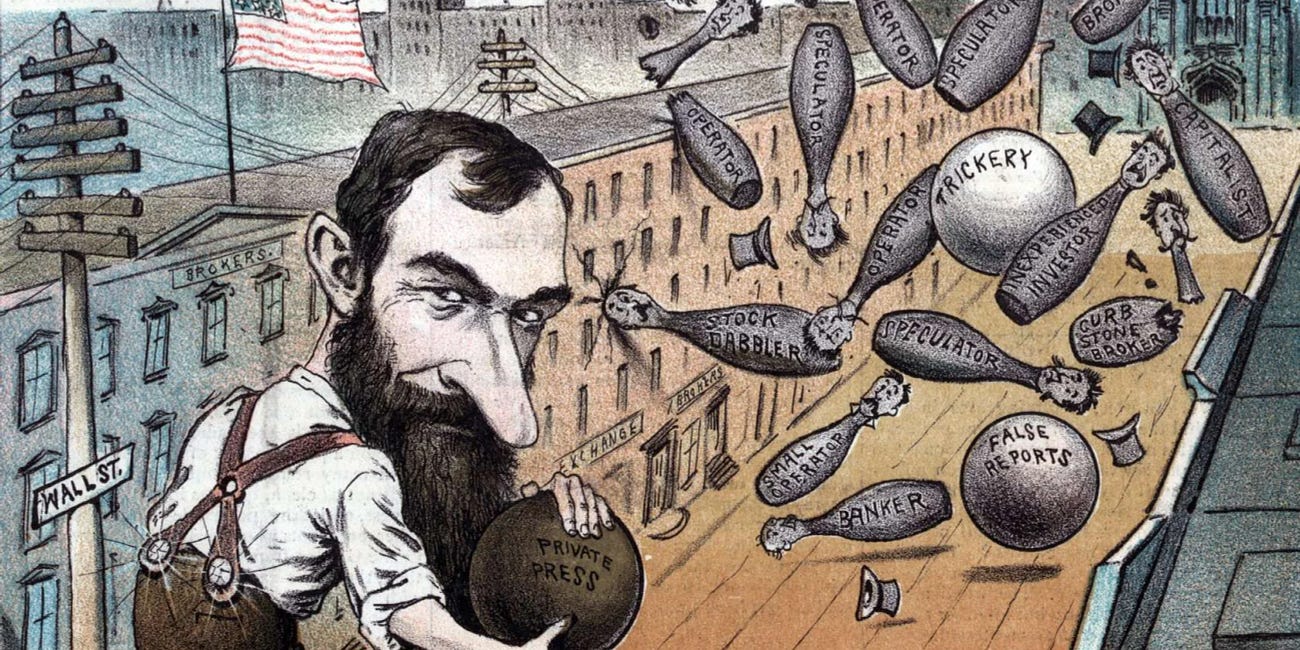

Kanigel also glosses over many important issues. Taylorism really did devalue certain kinds of skilled labor, and the costs have been high. The “Taylorized” doctors of the HMO era, for example, must work with administrators peeking over their shoulders, dispensing pills at the expense of empathy and other unmeasurable healing skills. And once factory workers lost their control and even their comprehension of manufacturing processes, many ceased to take pride in their work and stopped making suggestions for improvement. This may be one reason why Japanese and European design is often superior to American. Taylorism also spawned the rise of management consulting, with its sham exercises and goals – at worst, a huge diversion of managerial talent in the name of efficiency. Kanigel, however, largely ignores this darker side of Taylorism; the true impact of his legacy gets lost in the details. The result is a 600-page profile of a narrow and compulsive man with a single, if influential, idea. It is for scholars and specialists, not the interested layman.

Related reviews:

How government engineers the development and function of capitalism

If you want to get an historical grounding in the American economy and politics, this is the best book I know. The issues are clear from the beginning: how can we explain the explosive economic growth of the last few centuries? Why are depressions – panics, liquidity traps, and the like – apparently inevitable? What impact do government policies have? F…

Economic revolution, evolution, and slow down

In 1990, I moved to Japan to work in the US Embassy. It’s hard to imagine now, but back then everyone in DC thought Japan was going to take over the world, at least as based on its economic growth rate. A slew of popular and academic books sang the praises of Japan’s hardworking managers, the prescience of its bureaucrats, the brutal rigor of its educat…

The factory as modernist artifact

As an economics writer, I have visited factories all over the world. I saw refrigerator manufacturing lines in China that used Maoist indoctrination-shaming to instill capitalist habits into its workers. I investigated child labor in Pakistan, where factories consisted of garage-sized concrete shacks, the workers sitting on straw and sewing leather hexa…