The factory as modernist artifact

Review of Behemoth: a History of the Factory and the Making of the Modern World by Joshua B. Freeman

As an economics writer, I have visited factories all over the world. I saw refrigerator manufacturing lines in China that used Maoist indoctrination-shaming to instill capitalist habits into its workers. I investigated child labor in Pakistan, where factories consisted of garage-sized concrete shacks, the workers sitting on straw and sewing leather hexagons into soccer balls for export. In Vietnam and Indonesia, I followed a safety officer into massive shoe factories that manufactured all of the major brands in the same complex, where he pointed out innovations for safety in sewing machine design. What they all shared was the use of human workers as replaceable cogs in a vast machine that distant managers and engineers designed for people they would never meet. And yet, every factory was unique, a world of practice and values unto themselves, some more humane, some much less.

According to Joshua B. Freeman, the large factory is one of the most important developments in the history of mankind, a massive combination of capital investment, organization, and technology. It helped to boost economic productivity to unprecedented levels, raising the living standards of nearly everyone on the planet, create urban agglomerations, exposing individuals to new ways of living. Of course, the factory had a darkside, in dehumanized labor, workplace dangers, and pollution as well as political unrest. In his book, Freeman offers a very general history of the mega-factory from its origins in 18th century Britain to its culmination in the US and its extension into Japan, China, and the Third World.

The evolution of the factory is not entirely linear, Freeman says, but it does tend to follow certain patterns. First, there was a kind of consolidation period, in which large number of workers were put together in a single location. Rather than piecemeal production of textiles in disparate locations – harvesting materials, spinning, weaving, and finishing in separate locations – all stages occurred in the same place, hugely speeding up the process and adding flexibility. Into the mid-19th century, these mills employed limited, if large-scale, machinery; they relied on artisans to make the parts mesh together and function, which hindered control by managers, that is, their functions and practices remained mysterious and many workers retained significant expertise, even trade secrets outside of management control. This factory represented a larger unit of organization and cooperation than had hitherto existed, enabled in part due to the steam engine. It was roughly akin to the pin factory that Adam Smith described in his Wealth of Nations. Finally, to bring farmers in from the countryside to work, capitalists began to create their own cities, such as Lowell, Massachusetts.

Second, beginning in the armaments industry in the early 19th century, there was a push for the standardization of parts. This required the invention of precision machine tools, the imposition of exacting standards, and the logistical network to support it. Once the notion was widely accepted, it was applied to virtually all industrial undertakings. This had the effects of diminishing the value of customized expertise and opening the understanding of the workings of the factory to entrepreneurs and managers, a significant loss of working-class power. Factories became far more precise and intricate. Interestingly, though there had been plenty of labor unrest in the earliest factories, these types of factories became more vulnerable to protest and disruption because of their complexity and the delicacy of some of their processes. Thus started the great contest that pitted managers against workers, spawning the union movement. A novelistic portrayal of this might be The Jungle by Upton Sinclair.

Third, in the late 19th century, Frederick Taylor recognized the need to develop a “scientific management” approach to enhance productivity, in which every detail in the working of the factory was measured, evaluated, and experimented with. If offering a major improvement in productivity, this movement (“Taylorism”) led to the atomization of tasks, with each worker performing a few motions all day, or perhaps even a single one. On the one hand, these developments were touted as harbingers of a kind of capitalist utopia, with ever-improving standards of living, etc. On the other, having lost their expertise and even understanding of the process, the workers themselves felt devalued, their work dehumanizing, boring, and poorly paid as unspecialized labor. This led to even greater unrest, sometimes at civil war proportions. Charlie Chaplin parodied this process of dehumanization in Modern Times.

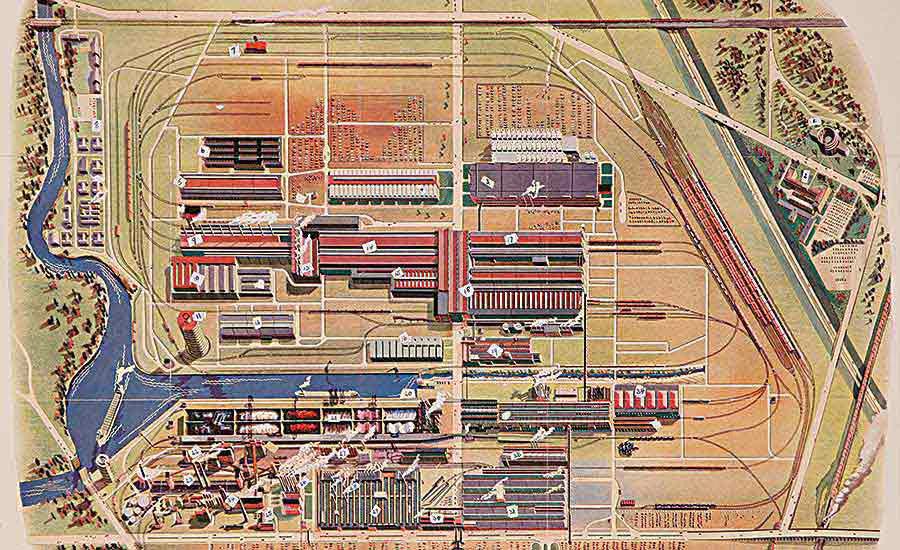

Fourth, extending Taylorism to its ultimate extreme, Henry Ford built absolutely massive factories in a fanatical pursuit of productivity and efficiency. These factories were the size of entire cities and functioned as a single machine. It makes me think of the industrial scenes in Voyage Au Bout de la Nuit by Louis-Ferdinand Céline.

In the US, this process was iterated into the 1970s, when it reached a point of diminishing returns. Freeman offers this as a key explanatory factor in the slowdown of productivity growth at that time, though not the whole story. Labor unrest was becoming such a problem that capitalists began to break up production and seek to build factories in areas less amenable to unionization, due to the relative poverty of new locations and less tangible political factors, such as cultural and even religious opposition to labor organizing. Eventually, this led to the globalization of production, in which parts were farmed out to factories all over the world, only to be recombined into final products. In their turn, the unions lost power in the 1980s and no longer benefitted as much from sharing in productivity gains, that is, managers claimed the lion’s share of profits, creating inequalities unseen since the Gilded Age. Across the US and Europe, once-prosperous cities could be reduced to rustbelt wastelands that offered few prospects of maintaining a middle-class life style.

Fifth, with the rise of the communist blocs, a kind of centralized industrialization took place in accordance with 5-year plans. Starting virtually from scratch, Soviet bureaucrats attempted to impose factory industrialization from above. To do so, they had to build factories, import technologies, organize labor, create entire logistical networks, and service non-existent markets for the heavy industrial products on which they concentrated. If fraught with bottlenecks and brutal authoritarian controls that sometimes included quasi-slave labor, the USSR proved that spectacular growth was possible by state-imposed initiative in spite of the Great Depression in the capitalist west. If their growth eventually stalled at the transition to a consumer economy, it was enough to threaten the foundations of capitalism to the 1990s, or so we thought. Interestingly, in Poland the massive factory complex in Gdansk was the birthplace of Solidarność, which the communist authorities were unable to fully control.

Sixth, there were the factories in the newly industrializing countries, including China. Combining authoritarianism and scale, they were able to exploit cheap labor and control their workers to a far greater extent than in the west, in large part because they remain almost invisible to critics and organizers. Freeman argues that, by largely concentrating on minor products such as consumer electronics, computers and smart phones, they are even more dehumanizing than car and textile factories of the 19th century. Freeman emphasizes that, following capitalist competition and innovation, the life span of factories, never long, continues to shrink.

These are very interesting ideas, if not particularly original. Freeman has provided a solid academic treatment that is accessible to the lay reader. The book is well written, fast paced, and a good synthesis. However, I wanted more on the origins of the factory. Why did it come at the time it did? What was the original model on which it was based? (Some historians, for example, argue that the model came from the shipping industry, which was expanding at the time due to Empire building as well as the disenfranchisement of farmers for the Commons in Britain.) Furthermore, while clearly acknowledging the pitfalls of the system, Freeman avoids getting into public policy, how things could be done better or indeed whether capitalism is reaching some kind of dead end.