Tumultuous nationalist machinations

Review of The Struggle for Mastery in Europe: 1848-1918 by A. J. P. Taylor

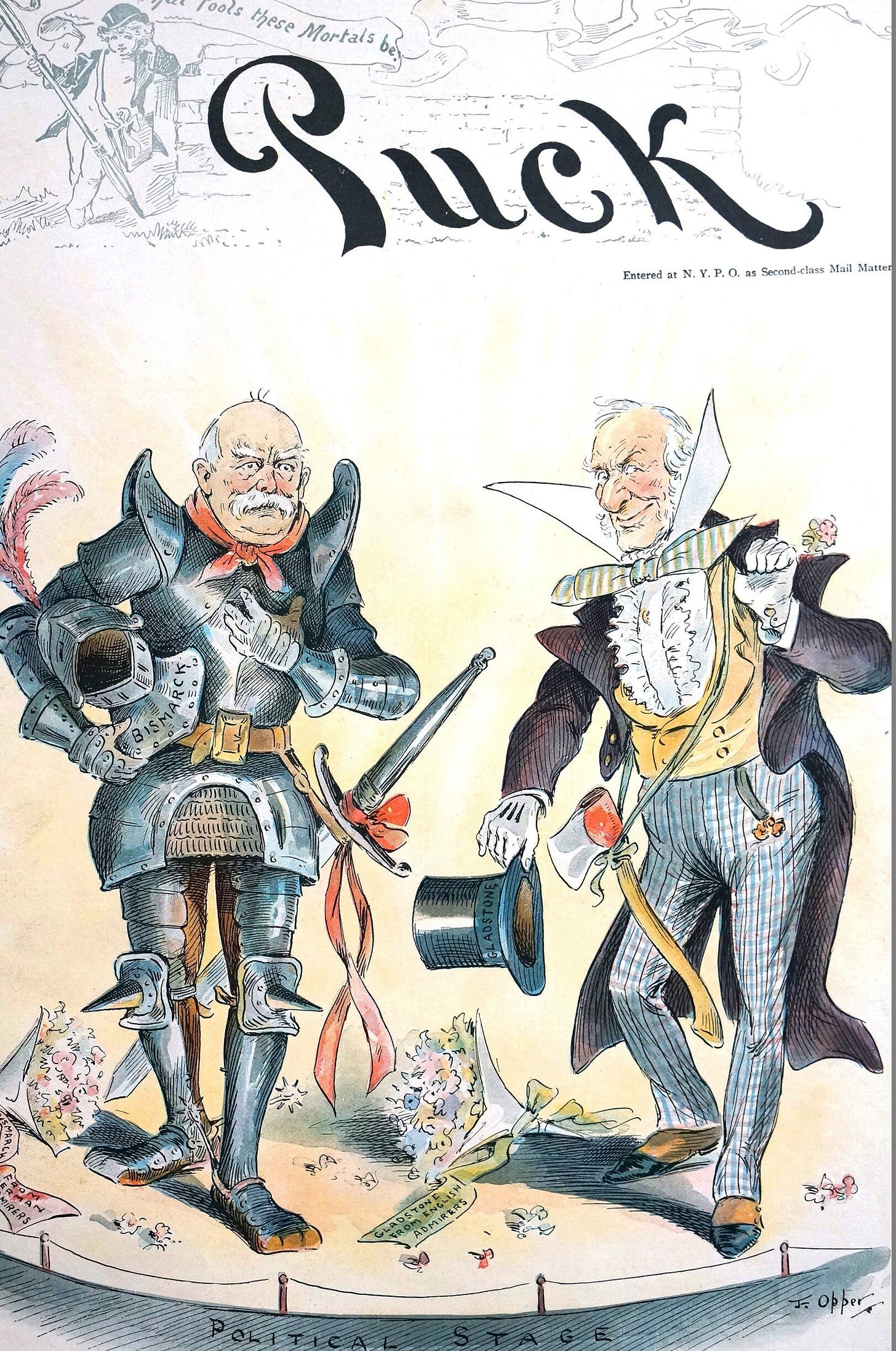

The beginning of the period, in the wake of the 1848 revolutions, marked the end of decades of "revolutionary diplomacy", in which the ideals of the French Revolution divided opinion and shaped diplomatic action. In France, Napoleon III had seized power and concentrated on more traditional balance of power diplomacy, as head of the most powerful nation-state at the time. The British were content to develop on their own, only stepping into continental entanglements when they could no longer avoid it. Russia, Austria-Hungary and Turkey appeared to be in terminal decline, though clinging to the perquisites of power in their respective multi-ethnic autocracies; the growing nationalistic ambitions of an astonishing array of players were threatening them with territorial dissolution. In the effort to unify the peninsula, Italy was having its own revolution. The great wild card was Prussia, at the beginning of the period a small kingdom that, under the leadership of a strategic genius, Bismarck, was slowly consolidating its hold over a vast territory of German speakers; it was a nation in birth, a coming industrial superpower with a huge population that would irrevocably shatter the balance of power.

Until 1870, these powers, perhaps the last time they could be called “princely”, struggled for the typical diplomatic fruits of the time: gaining territories, trade rights, and any number of privileges or concessions from each other. The complexity of these concerns is daunting and almost without exception obscure, even personal, but they were indeed the principal concerns of the leaders of the time. When disputes reached a certain point of impasse, they were often resolved by small-scale war, giving the victor the spoils of whatever was demanded, be it passage into and out of the Black Sea, domination of Poland, or control of the Suez Canal for trade with Asia. The book attempts to cover every single one of these disputes, showing exactly what was contemplated in chronological succession and what happened in the end. Some readers seem to like this detail, and the gist is important to understand, but a lot of it is now historical trivia of little interest, at least in my estimation.

Each power was juggling so many interests that the whole was like a dark forest of thorny complexities, secret agreements, and tenuous alliances of mutual benefit. It was like they were all playing chess on the same board – some controlling the major pieces, some smaller ones, all in potential conflict or cooperation at one time but not another, and variously placed with regard to natural and economic advantages. Another analogy that comes to mind is competing LEGO constructions on a common board, each player endowed with its own array of pieces that they traded and fought over or, occasionally, used collaboratively.

Beyond the petty wars (to 1870), there were 3 major engagements that led to decisive consequences. 1) The Crimean War removed Russia as a top-tier player until after World War II. 2) The Prussian victory over Austria-Hungary reduced the latter, with all its ethnic divisions, to a dependent power, ratifying German domination of central Europe. 3) In 1870, France fell from the apex of power, when it capitulated to Prussia after a brief war.

The Conference of Berlin led to the longest period of peace in Europe since the Roman Empire. Over the next 40-odd years, European diplomats played the game of the balance of power, all the while investing in the new determinants of power: commerce, heavy industry (in particular steel production), and military technology; they avoided outright large-scale war. The two greatest achievers in this realm were Great Britain (with its mechanized navy) and Germany (split between navy and ground forces), leaving others behind in one or more areas; not coincidentally, they also had the most advanced industrial economies. They created innumerable systems of alliances, peacekeeping, and trade, but all for traditional parochial reasons rather than in accordance with strategic or multi-lateral vision. It should be noted that many of their motivations were face-saving and for appearance and prestige, for increasingly they had to take public opinion into consideration. This triviality added to inflexibility. Clearly, the time that princes and their aristocrat-functionaries could dominate the scene was ending – concerns were becoming nationalist and, timidly, democratic or at least, more inclusive.

The outbreak of World War I is part of a long discussion in the book. This was the most interesting dissection of diplomatic detail in the book. According to Taylor, the bottom line was that the various powers thought the Great War would be short and decisive. Germany wanted to dominate Europe and thought it could do so by aggrandizing its territories. France, Russia, and Great Britain feared this and hoped to preserve the balance of power to their advantage. Austria-Hungary and Turkey wanted to maintain the integrity of their territories against the centrifugal forces of ethno-linguistic groups; this slanted both towards a crude ethno-linguistic nationalism, upsetting the tenuous internal balances they had maintained over centuries. Oddly, none of the major powers seemed to have any clear goals, backup plans, or even coherent strategies for a major war, but went into it as a way to impose solutions to their advantage by force rather than diplomacy – that is, the conventional way things had been done prior to 1870, but with far more advanced military machines that mobilized not just whole populations but industrial nation-states. Once started, no one could back down without losing face. It became a catastrophic war of attrition, bringing in the USA and ending the European era of world domination by 1918.

This is the story, told almost exclusively from the point of view of the diplomatic players. The focus of the book is what leaders were thinking, how they pursued their goals, and the outcome of their machinations and wars, most petty, some major. This approach (diplomatic history) contrasts sharply with analytic or narrative histories whose principal aims include the search for broad trends, the interpretation of deep, underlying causes, and portraits of culture and everyday life. Instead, here, you get what the powerful were trying to do, literally from moment to moment. For myself, while fascinating in many aspects and essential, I found it rather dry as a reading experience.

I believe Taylor's interpretation of the European modus operandi – the fight to maintain yet disrupt the balance of power – is correct. What I missed was a lively narrative with biographical texture and descriptive detail. I know that that is not part of the strict discipline of diplomatic history, but potential readers should be aware of this.

Related reviews:

The unbelievably intricate path to catastrophe

The title, The Sleepwalkers, says it all. I have never understood why the great powers of Europe went to war in 1914 and after reading this, it is clear that they did not know either. This book is about how it happened, in a huge narrative on all the contributing players, from the tubercular assassin of Archduke Ferdinand to the ineffectual Tsar in Russ…

Attempts to elucidate the sociological factors in 19th century history

History books tend to move between narrative and analysis, or put simply, a story vs. an interpretation of the forces and trends behind events. The narrative stresses the role and impact of individuals, while the analysis looks to abstractions and ideals. Osterhammel’s book skews as far to the analytic side as may be possible, in a sense it is a sociolo…

Debunking 19th century nationalist ideologies by historical proof

This is a very fun essay, designed to make us examine the mythology behind the nationalism that arose at the end of the 19th century, as supported by myths of ancient heroism or lineage. It is supposed to be for the general reader, not the specialist, but I think it is rather rarified in terms of the details he gets into. To prove his point, he gets ver…

The mother of all turning points, even if it didn’t quite turn

I have long sought a detailed account of 1848: it was a time of myriad movements, crises, hopes, violent revolutions, and even more brutal counter-revolutions. As a moment of such utter complexity and import, it is key to understanding the tensions of the present day. While this uneven book dwells too much on the details of the violence and political ma…

I am very much enjoying your synopses and critiques of these books. The thing that strikes me in my readings about the Great War is that they all MEANT to go to war-they just didn't mean to go to the war they got. The combination of explosive shells and machine guns (and the industrial power to produce them in a seemingly endless supply) seems to have caught them all by surprise.