In the 1830s, a small St. Petersburg group – Bakunin, Herzen, and Belinsky – emerged to proclaim themselves the intelligentsia. It is a Russian word, denoting not the straightforward interest in ideas of intellectuals, but a kind of secular priesthood devoted to a mission that should change the world. According to Isaiah Berlin, not only did they lay the groundwork for the Russian Revolution, but they created a unique form of social criticism, that is, art for didactic purpose.

The historical context they were operating in was tumultuous. In an attempt to drag Russia out of the medieval ages, Peter the Great (r. 1682-1725) had sent a cadre of young men to Western Europe. They were supposed to return as modern thinkers, imbued with Enlightenment ideals, but they had turned out to be too subversive for the Tsar’s taste. As a result, the primitive Russian state alternated between openness and erratic efforts at repression. Catherine the Great (r. 1762-96) was sympathetic to the philosophes, but the excesses of the French Revolution discredited them, leading to renewed repression by her successor, Alexander I (r. 1801-25). Once the allies had defeated Napoleon, Russia emerged with a new sense of nationhood, even of destiny to become a great power and perhaps a unique moral force. However, the base of Russian society remained extremely thin: aristocrats controlled resources; below them were the peasants, who formed upwards of 90% of the population. There were very few educated thinkers in a vast sea of ignorance. As a result, the intelligentsia was ravenously hungry for ideas, often accepting them naively and uncritically.

The Enlightenment philosophes were coming under heavy criticism. Beyond their failure to either predict or control the political violence unleashed by the French Revolution, the philosophes, Berlin informs us, were increasingly viewed as too materialistic, too cold in their attempts to build a sure “science” of government and morals. Moreover, as investigated by theory and observation or experiment (the scientific method), their clockwork universe lacked overall purpose and poetry. Events in France also seemed to prove that they merely promoted the illusion of control via the application of reason. This opened the way to new perspectives, in particular the German Romantic Movement, which especially appealed to the intelligentsia.

Hegel profoundly influenced the Russian intelligentsia. He elaborated on the idea that history was moving in a recognizable direction, that it was the individual’s duty to conform to this ideology, which was leading to a new kind of society, a heaven ON earth of freedom, equality, and justice. Rather than arrive at conclusions by the application of reason and observation, the Romanics argued, men should trust their intuition of the truth, their spiritual vision, even their sense of aesthetics and art as the deepest truth. Society was envisioned not as clockwork cosmos with objects on their own independent trajectories, but as a biological organism or an intricately interlinked environment, a whole in which each part played its designated role. Indeed, each individual had an obligation to participate in the way that the overall spirit of the times dictated. This pushed their political vision into the future, where in spite of setbacks and perhaps regretful expediencies in violence and repression along the way, better times were to be had. Berlin emphasizes that although this was well before Lenin and even orthodox Marxism, the Romantics laid a fertile foundation for these later ideologies to take root.

The intelligentsia included a number of flamboyant and brilliant exemplars. Though perhaps best known, Mikhail Bakunin was an agitator and anarchist of sorts with no consistent ideology or policy. Berlin characterizes him as “a gay, easy-going, mendacious, irresistibly agreeable, calmly and coldly destructive, fascinating, generous, undisciplined, eccentric Russian landowner”. In other words, he was a dilettante and demagogue.

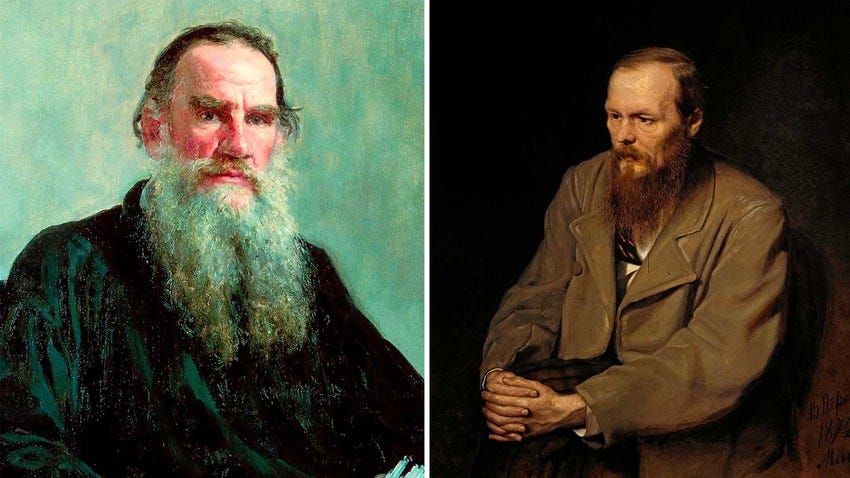

Vissarion Belinsky was, in Berlin’s opinion, a far more worthy member of the intelligentsia than Bakunin. An “inspired and fearless publicist”, Belinsky was a literary critic who became the “conscience” of a generation of young idealists, or révoltés. He sought the truth in art, the meaning and import of which he would explain to his audience. Pushkin, Dostoyevsky and many others were championed by him. The moment in which he was writing (d. 1848) was one of transition away from the artificial mimicry of French culture that dominated the Russian Aristocracy in favor of homegrown literature in the vernacular language of the masses. In effect, his criticism crossed class lines and in the process, helped to create a new social consciousness. While believing in science, he also searched for Hegelian truth and ideology.

Alexander Herzen is perhaps Berlin’s intellectual hero in this book. Living most of his active life in exile, he alone was the skeptic regarding Hegelian-style ideologies. His great enemy was “the terrible power over human lives of ideological abstractions”, precisely the grand conceptions that would sacrifice freedoms of both individuals and society in the present for some imagined future, a secular eschatology that was a delusion and cheat. In this sense, like Berlin, Herzen appeared to be a classical liberal, favoring debate and conflict over the narrow “certainties” that elites might prefer to impose. In Herzen’s world, human affairs were messy, demanded multiple, sometimes conflicting, solutions and offered no guarantees of outcome or even resolution. A proto-existentialist.

Isaiah Berlin, I believe, is one of the greatest intellectual historians of the 20th Century. His prose is so dense that ideas and brilliant characterizations seem to leap from every page.

Related:

Repressive regime as precursor to Soviet totalitarianism

Richard Pipes has a principal theme: in the area that became Russia, the land was extremely poor, which restricted economic possibilities and warped its society. His entire book is an application of this theme to the history of the Russian state: if akin to a survey history, it is intended to drive this point home.

Political, economic, and social history of the Enlightenment

The book begins in the aftermath of the Thirty Years War, one of modern Europe's most devastating conflicts. In many ways the ultimate religious war, it also dealt a decisive blow to many feudal arrangements and customs, opening the way for the birth of the nation-state. Feudal society was based on the triad of clergy, aristocrats, and an emerging bourg…

How Enlightenment philosophy developed and was applied in the real world

Gay’s ambition with these two books is to describe the Enlightenment mindset and assess how the philosophes’ ideas worked out in the real world. What was new and different about them? How did they change our approach to science, psychology, society, then political science and government? What was their practical impact? If you want answers to these ques…

The movement celebrating darkness, individuality, and wholeness

From the moment that Rousseau rebelled against the Enlightenment – with its assurances that everything could be known and arbitrated by reason – a new and unruly movement emerged. The Romantics would challenge what we can know, how we should study the world and ourselves, and questioned even the precepts of happiness and the "good life". As Blanning pro…

The explosive development of Russian Culture

Not only is this a deep literary work in its own right, but it offers a series of riveting narratives that review Russian history from the time of Peter the Great (d. 1725). It is also simply fun to read and brilliantly reviews the historical context.