Marx is one of those protean writer-activists that supposedly shaped a century, both prophet and ultimate villain. This book is neither a vilification nor a hagiography, but a straightforward look at what he thought and did, an introduction to the nexus of ideas and politics he absorbed and shaped in the 19th century. It is a completely satisfying intellectual meal, as is always the case with Isaiah Berlin.

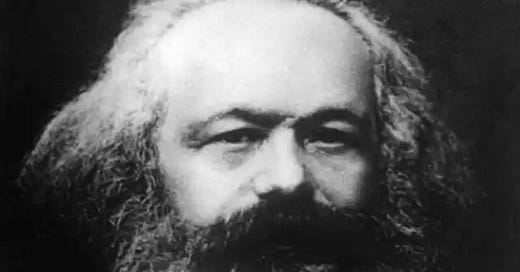

Karl Marx was born in Trier, the grandson of a rabbi. His father, a lawyer, had benefited from the Napoleonic Code that opened careers to German Jews, though he was obsequious and cautious, ever fearful of the Prussian state. Karl was rebellious and outspoken, but he was lucky in that an enlightened gentile (Ludwig von Westphalen) took him under his wing; Marx later married his daughter. Early on, Karl showed a penchant for rigorous study and quickly dropped law for philosophy in Berlin, where Hegel's ideas remained vitally current.

Enlightenment ideas – that the world could be known and controlled with absolute certainty through observation and the application of reason – was already under attack from the Romantics. Hegel, a philosophical idealist, offered one of the most well developed counter-Enlightenment systems, which involved a holistic methodology to look at all aspects of history and society in a search to discern the Hegelian "Spirit" of the age, that is, the principal idea or trend toward which everything was heading. Marx embraced and then rejected Hegel’s Spirit as vague and quasi-mystical, especially as applied by utopian "Young Hegelians". He turned his researches elsewhere.

Retaining the structure of Hegel's method (thesis, anti-thesis, and synthesis), Marx incorporated the ideas of Saint-Simon, a proto-sociological analysis of the behavior of elites; according to Saint-Simon, elites gained advantage with their talents when new conditions arose but then became concerned with the preservation of their privileges to such an extent that they lost the ability to adapt once circumstances changed. For example, aristocrats wanted to preserve the feudal system but were being swept away by the rising entrepreneurial bourgeoisie. He then absorbed the materialist ideas of Feuerbach, who argued that "real causes" lay beneath whatever the stated reasons might be. Eventually, Marx concluded that economic interests were the "Spirit" that animated history. This, Berlin argues, was a new kind of synthesis, the first sociological theory of society as an evolving system. It was a whole new attitude and method that, even as much of it proved erroneous, was a major contribution to the social sciences.

From this, Marx laid the foundation for his ideological view of how industrial societies would evolve. The bourgeois were great innovators, creating technologies that enabled manufacturing industries, but now they were becoming parasites in their own turn, skimming value and surplus from the workers' labor in a way to keep them under control. There were many mechanisms of control, such as religions, but also incremental reforms and the gradual acquisition of rights. Marx believed that all of these were chimeras that camouflaged power relations and he vehemently denounced them. For him, the inevitable and only way ahead was violent revolution as led by the proletariat, a seductively messianic vision. On what would follow, Marx remained vague, though at times it appeared to be an Athenian-style democracy.

Of course, advocating these views in such tumultuous times got Marx into trouble. He fled Berlin, then Paris, then Brussels, finally ending up in the relatively tolerant London. In his exiles, he witnessed the failed revolutions of 1848, studied the Paris Commune, and analyzed a great number of other upheavals that he portrayed as flawed harbingers of what was to come. He also spearheaded revolutionary organizations and spent a lot of time in-fighting with the likes of Bakunin and Lasalle. These historical evocations are great fun and come interspersed with some pretty abstruse philosophical arguments where the thread of the narrative can get lost.

His personal life is also covered, but only peripherally. He lived in poverty, three of his children died because he couldn't provide them better living conditions, and he had a happy marriage if few real friends, Engels excepted. He comes off as a neurotic, authoritarian man of genius.

This is a great and updated version of Isaiah Berlin’s masterpiece. There is an elegance and lucidity to his writing that I find in no other political philosopher.