The most consequential failure in American history

Review of Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 by Eric Foner

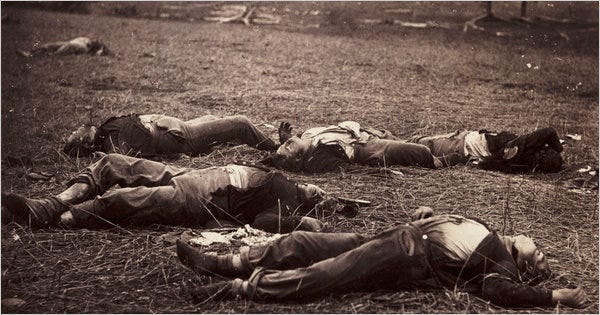

Reconstruction was an immensely complex task: the South was supposed to be rebuilt but also submit to the transformation of its society and economy to rid itself of the legacy of slavery, as imposed by the North. Slaves had never had a chance to grow into the habits and customs of a free market economy. Meanwhile, their erstwhile owners believed they were capable of nothing but dependence and sloth, constitutionally in need of the whip. Reconstruction also had to overcome racism, an imbalance of power both economic and military, and create a market economy where there were only plantations accustomed only to the most rarified forms of competition.

Foner starts with a sketch of the historiography of the Reconstruction, i.e. on the period from 1865 to 1876. Needless to say, the long-reigning "Dunning school" of historians drew a pathetically inaccurate picture that played to Southern vanities and pride, according to which Andrew Johnson was a sincere and good man who was stymied by the evil meddling of reformers from the North. This view was overturned only in the 1950s, when the civil rights movement sparked a fundamental reexamination.

The institution that was tasked to lead reconstruction was the Freedman's Bureau, which had been conceived only as a stopgap measure for one year. However, by default after Lincoln's assassination, it became the principal instrument through which the policies of the Federal Government were to be conceived and implemented, with little concrete guidance. Its mandate was a mishmash of contradiction and wide, ill-conceived responsibilities, comprising education, land distribution, oversight and enforcement of free-market contracts between former slaves and their employers, and not least, the administration of justice. Not only did it lack the means to do so in any practical way, but it didn't even have its own funds, dependent as it was on the Army's budget. This institutional inadequacy is a major theme of the book.

However well intentioned, the Freedman's Bureau was also burdened with a simplistic economic ideology – "free labor" – which assumed that because the interests of capital and labor naturally should coincide, they would be willing to cooperate in the development of the new-style market economy. Unfortunately, the "free labor" theory neglected racist antagonism and class conflict, offering no practical policy guidance whatsoever.

In the face of this muddle, Lincoln's successor, Andrew Johnson, didn't believe in the Bureau and sought to undermine and shrink its mandate, perhaps out of a mix of racism, white supremacist preoccupations, and political convenience. As a result, in the crucial early years when it could have accomplished a great deal due to the exhaustion and acquiescence of Confederate notables, a unique opportunity was squandered. Instead of land distribution (40-acre plots and a mule to create economically independent freedmen), within a few years Federally confiscated and abandoned lands were back in the hands of their original owners, or at least members of their class. The former slave owners were proud, bitter men who demanded the deference and subordination to which slavery accustomed them, ready to resort to violence at the slightest provocation.

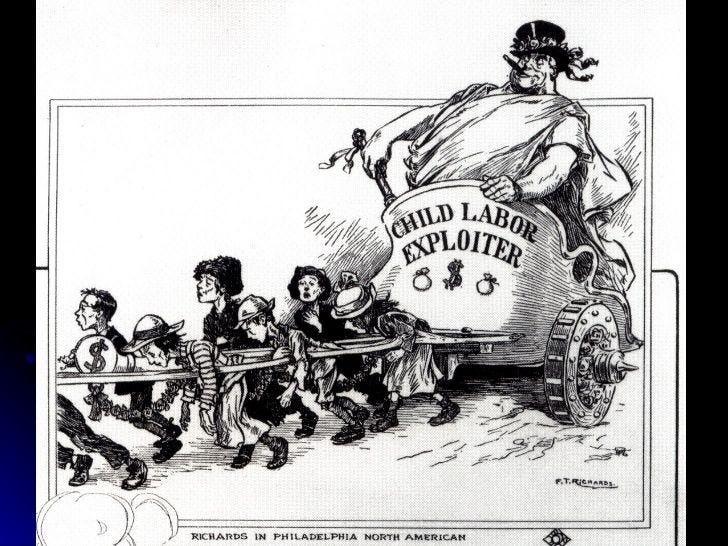

For their part, former slaves themselves were extremely active and ambitious, entering politics, establishing schools, businesses, and churches. Unfortunately, as the power balance shifted back to the old order, the Federal Government under Johnson willfully ignored the reign of terror that ensued. Eventually, reactionary whites, through organizations like the KKK, came to dominate Southern society, allowing blacks their churches and schools but little else. This led directly to the Jim Crow regime in the 1890s, a brutal system of segregation and lawlessness that lasted into the 1960s. From expediency and habit, the economic system that emerged was sharecropping, which allowed blacks to at least escape gang labor and work without direct overseers, but condemned them to poverty and exploitation.

The Washington establishment didn't sit passively as all this occurred, but it failed to accomplish much. Once Johnson was out, President Grant and others made many sporadic attempts to remedy the situation, shutting down the KKK, for example. But it was too little, too late. With the start of the Great Depression of 1873, the North seemed to lose interest, cutting a political deal to end reconstruction in exchange for the political support of white Southern notables in the stolen election of 1876; in the process, it shamefully abandoned its allies to fend for themselves.

This is one of the best history books I have ever read. It is a monument to the most grotesque failure – of nerve, of policy, of justice, of historical necessity. Indeed, it is a profound statement on the limits not just of our institutions of the time, but perhaps even of human nature. Yet in spite of all this, Foner sees that some progress was made. Slavery had ended, some rights were established if only in embryo, and African Americans had more leeway to decide things for themselves, such as changing location; many were educated and learning to work in the marketplace. Unfortunately, our institutions were so weak that they were not up to the task and national political will died with economic crisis of 1873.

Related reviews:

Masterful history of a time of great upheaval

If you think that the present era is bad, all you need to do is read about the Reconstruction to see America at its absolute worst. This book covers the close of Reconstruction, into what has long been portrayed as an era of explosive "progressivism". It is a kind of people's history as well as covering the actions of leaders. The result is a brilliant …

Review of America Aflame: How the Civil War Created a Nation by David Goldfield

I have some close, much-loved relatives in the South. Way before the advent of Trump, we had strongly divergent points of view. As a child, their father’s mix of radical libertarianism and open racism often shocked me; his religion made him impregnable. He vehemently denied that the Civil War was about slavery. In his view, it was about states’ rights a…