The great, little known gem of early Christianity

Review of Ravenna: Capital of Empire, Crucible of Europe by Judith Herrin

Ravenna is a unique historical site with spectacular mosaics and quirky, early Christian churches, including an (extremely rare) intact Arian chapel. I have long wondered about how the city arose as the western Roman Empire was collapsing, surviving iconoclasm and barbarian invasions as an outpost of Byzantium before falling into obscurity after nearly 300 years of preeminence. Ravenna set architectural and artistic standards for the emerging medieval culture, became a major commercial center, and set a fleeting example of religious toleration in a repressive age.

Herrin approaches Ravenna not as a story of the end of the classical era, but as a new beginning, in particular at the time when Christianity was establishing its final forms after a long period of violent doctrinal turmoil. Of course, the western Roman Empire was under siege from “barbarians” and Rome itself had long ceased to serve as anything more than a ceremonial capital. With the Goth invasions around 400 CE, the situation had become so dire that a new Imperial Capital was founded, Ravenna, in 402. The site was chosen for its geographical features – difficult to access in a marshland with a defensible harbor onto the Adriatic, it appeared impregnable. While Alaric sacked Rome in 410. The west was collapsing as waves of Germanic tribes swept into the Italian peninsula.

At this point, a number of remarkable personalities emerged, all with the expectation that Rome would be restored to something like its past glory. Moved to West Rome, the Byzantine princess Galla Placidia had been taken hostage by Alaric during the sack of Rome in 410. Of extreme potential value to future negotiations, she remained a prisoner for several years, eventually marrying Athaulf, a Goth King; the marriage was a symbol of the barbarians’ “fealty” to Roman law and institutions, but with a Gothic character (which included the Christian heresy, Arianism, which de-emphasized the divinity of Christ). No one knows if she did so willingly or under duress, but she lived with the Goths until they traded her, now a widow, for 600,000 measures of grain. In her mid-20s, she become Empress of West Rome and remained deeply involved in government for the rest of her life (d. 450). Able to attract the best artisans and architects from both east and west, Galla essentially shaped the architecture and art of the capital as well as its forms of faith. This was the time when the western Empire fell decisively to the Germanic tribes, particularly with the loss of North African wheat imports in 439 as well as the Vandal sack of Rome in 455, which was far more destructive than had been the reluctant Alaric. From this point on with few exceptions, barbarian chieftains ruled in the west.

Theoderic had grown up as a voluntary hostage in the court of Constantinople. Educated in Greek and Latin, he had learned how the imperial administration functioned and conducted diplomatic and military initiatives. Leaving on good terms with an official mandate, he entered Italy with a force of approximately 300,000 and conquered most of the Italian peninsula in the late 5th century. He chose Ravenna as his capital. Though Arian, Gothic warriors were the principal members of his court, signaling his political autonomy; Theoderic officially operated as a representative of the Emperor Zeno in the west. Beyond a massive building program, his administration was tolerant of religious diversity, including a large Jewish community in Ravenna, a balancing act that set an example of civil peacekeeping. He died a revered figure in 526, but the mosaics of him were later covered over by a Catholic Bishop. When I lived in Bologna, I often looked at the blank space and wondered what he had looked like.

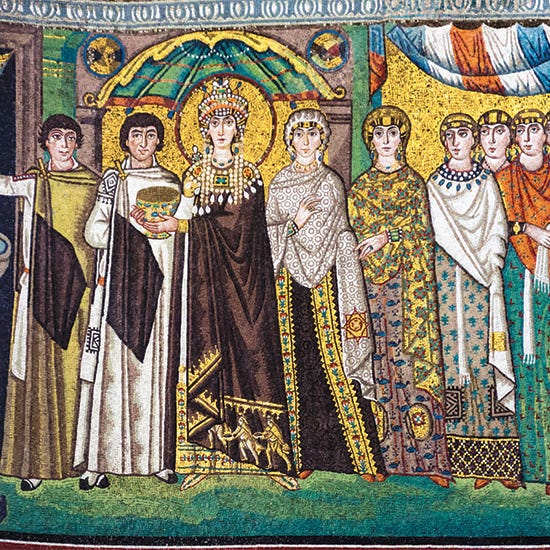

In 533, the last significant attempts to recapture the west – the remnants of Rome were then ruled from Constantinople in the east – were Justinian’s Wars. His great general, Belisarius, overran the Gothic kingdom in Italy. This decisively established Ravenna as the center of imperial administration in the west, eclipsing Rome for the next 200 years as well as finally snuffing out the Arian schism. Justinian embarked on a massive building binge, including San Vitale, the Cathedral with many of the most vital Christian mosaics of the early middle ages. For a time, Ravenna became a great center of learning in medicine and other fields as well as a major trade hub for Western Europe.

Justinian’s hegemony was short lived. In the late 6th century, another group of Germanic raiders, the Lombards (literally, “the long beards”), invaded Northern Italy. While Ravenna perilously remained an independent outpost of Constantinople, the Emperor decided to appoint an Exarch to run the city; essentially a military dictator, he represented the end of local governance. The Lombards later annexed Ravenna. It was not until Charlemagne that the Lombards lost their territories in Italy, 774.

Meanwhile, the great traditional adversary of East Rome (Byzantium, though it was never called that in late antiquity) was the Sassanian Empire, a Persian dynasty whose rival monotheism was Zoroastrianism. Neither Empire noticed the rise of a new threat: Islam, as inspired by the Prophet Muhammed (d. 632). Perhaps in part because Rome and Persia had exhausted themselves in centuries of conflict, Muhammed’s successors quickly overtook Palestine and many other territories. If Byzantium – severely weakened by the loss of its tax base in the eastern and southern Mediterranean – survived in truncated form, the Sassanian Empire was completely decimated, eventually adopting the Muslim faith. The upshot of this was that Ravenna and Rome were increasingly on their own.

It was at that point that Ravenna began to become a near-forgotten backwater. For posterity, this was a fortunate development. Observing that victorious Muslims banned all holy figurative imagery, Byzantine Emperor Leo determined in 730 that the Christian veneration of icons may have angered God, hence their battle losses were a “punishment” for violating the Second Commandment. This resulted in iconoclasm, a massive effort to remove or paint over images, which most of Ravenna’s fantastic mosaics escaped. Today, Ravenna offers a unique window into early Christian imagery, indeed the mosaics are so vivid that they can be interpreted as statements on the characters of saints and rulers. They must be seen to be believed.

Herrin offers an extremely full intellectual meal. Chock full of historical and theological detail, the book moves briskly and can be read on many levels.

Related reviews:

Emergence of Arab Islam and the end of Antiquity – in context

This book covers a seminal historical nexus, marking the death of classical civilization and the beginning of the medieval period. At the center of it is the rise of Islam, which would become the dominant cultural and military force for the next 800 years.

Splendidly incisive essay on the eclipse of classical culture

This is one of those history books that defines the era, setting a standard that is either accepted or opposed by all who follow. Because the end of the classical culture is one of the turning points that most fascinates me, this book was a particular pleasure, at once an over-arching synthesis yet accurate in its evocation of detail.

A dense essay to refute the "revisionist" view on the Dark Ages

This is less a narrative history than an essay taking aim at current academic fashion to portray the first few centuries of the Dark Ages not as an abrupt and brutal discontinuity, but as a prolonged continuation of "late antiquity", in which much of Roman civilization was absorbed and used to sustain the new masters of Western Europe, the Goths, Franks…

Intellectual history on the political impact of early Christianity

This book offers a detailed interpretation of what Christianity meant and the political impact that it had. Siedentop takes the reader on a long historical inquiry, from before the Bronze Age to the end of the Middles Ages and supposedly to the present day. While disagreeing with much of it, I was riveted by the ideas from the first page.