The era of our greatest political failures

Review of The Republic for Which It Stands: The United States during Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865-1896 (Oxford History of the United States) by Richard White

If you want a book that covers the failures of Reconstruction, the excesses of the Gilded Age, and the growing domination of industrial capital, this is a great place to start. During this time, the political and economic rights of black freedmen were disappointed then crushed, Native Americans faced their decisive, final defeats, and vast new corporations triumphed and went on to gouge their workers and consumers; meanwhile, American politicians and institutions utterly failed to address these issues in any lasting way. In spite of this extremely bleak picture, Prof. Richard White also argues that a number of reform movements were struggling to emerge, from suffragists to would-be regulators.

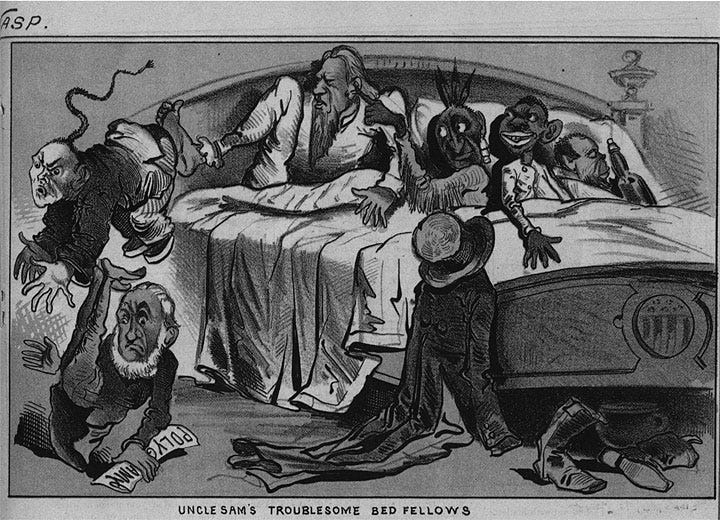

A central concept in the book is the notion of "home" as the organizing political theme of its time. In accordance with 19thcentury classical liberal ideology – that the market would take care of everything, so long as individuals were free to participate politically and as contractors – homes were supposed to establish their independence in small communities like that of Springfield, IL. It was presented as the natural order, according to which an extended nuclear family could worship, work, and live in the way they chose, as their own bosses on an independent farm, free from the meddling of government. Beyond providing for the common defense, the only thing that the Federal Government should do was protect private property. A naive, idealistic version of events, this ideology completely ignored a number of glaring realities, including: the particular difficulties faced by anyone who was not a white male; the new power bases that were emerging, such as the massively rich capitalist class; the truncated political rights that were falling to violent repression; unprecedented corruption; worsening poverty; the extraordinary and concentrations of wealth on a scale beyond any in human history; environmental degradation; and rapidly deteriorating conditions of health in the new cities.

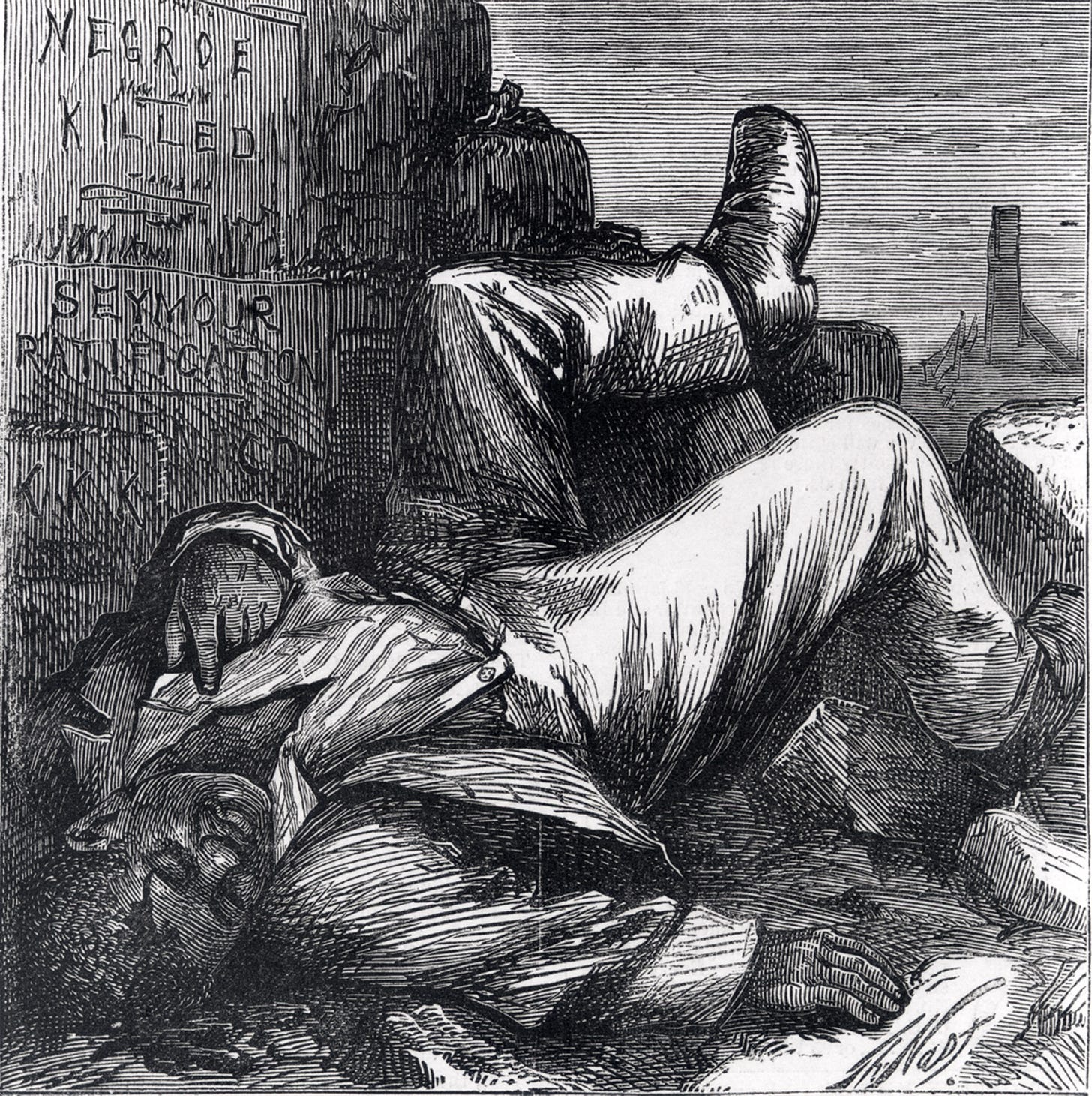

The first great failure in the story is Reconstruction and its immediate aftermath. Though begun with high idealism and hopes that freedmen would get 40 acres and a mule from busted up plantations, from inception it endured the hostility of President Andrew Johnson, who did everything in his power to stymie its policies. As the traditional elite firmly re-established itself in the south, it enforced its takeover by violence, eventually leading to a kind of serfdom for most freedmen, either as sharecroppers or bonded labor, due to misapplied laws. To be sure, there were new Constitutional Amendments that guaranteed civil rights, but they were rarely enforced, hence abjectly impotent. To resolve the deadlock of the 1876 presidential election, the Republicans made a deal, leaving the south to its own devices in exchange for the Hayes Presidency. Jim Crow became the institutional norm for the next 100 years while northerners turned a blind eye to segregation and virtually sanctioned terrorism, that is, lynching.

Second, in spite of the enhanced powers of the Federal Government on paper, the expansion into the west was chaotic and at the severe expense of the rights of both Native Americans and Mexicans, many of which were negotiated in worthless "treaties". The principal power of enforcement lay almost exclusively with the Army, which lacked the skills, finesse, and reach to conduct its political mandate effectively. Beyond the low rate of success that many homesteaders achieved (about 1/3 of them failed, mostly in the Great Plains), the human toll was indescribably bleak. This was genocide, expropriation, and degradation, much of it illegal.

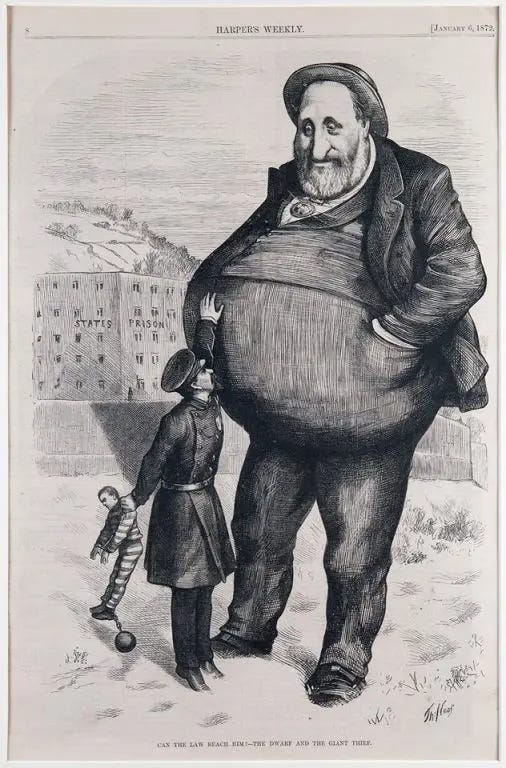

Third, as the Federal administrative apparatus grew along with its mandate, its institutions remained severely under-developed, with expanding opportunities for corruption. Rather than a salaried professional work force, officials had to be funded largely on a fee basis, i.e. payment in the service of one's duties like a Roman tax farmer. This did not help efforts to provide sanitary water, sewage disposal and the myriad efforts underway to make rapidly growing cities safe and clean. The situation was improving slightly by the end of the period, 1896.

Fourth, the industrial revolution was entering into full swing, from garment mills to railroads, steel production, and electrical products, including the telephone. Industrial bosses became so powerful that they attempted to lower real wages as a way to increase their profits, leading to an explosion of class violence that could be regarded as a civil war. Urbanization accelerated so rapidly that life expectancy declined as people lived in squalid tenements that were the antithesis of "home"; the workplace became salaried and authoritarian – the polar opposite of the idealized, independent yeomen that liberalism predicted. In this period, the development of the consumer economy was far in the future, even with the basic inventions there. At the same time, economic depressions recurred with stubborn, near-predictable regularity, which liberal economists claimed would easily remedy themselves without government intervention; this was a purely ideological belief and patently false claim against all evidence.

Fifth, political initiatives to remedy the problems of industrial capitalism were increasingly derailed by the decisions of judges, who also subscribed to liberal ideology, even as it began to fall from favor in academia. As such, the will of the people, as passed into legislation by elected representatives, was repeatedly thwarted in favor of big capital bosses. Combined with efforts to shrink voter rolls, the American people were poorly represented while blacks, Mexicans, Chinese, and Native Americans were almost completely disenfranchised as citizens; the plight of women was little better.

Under the surface, there were many positive developments underway, but they remained embryonic. Some of them would be enacted in the coming decades (the Progressive Era, which is not covered in this volume). They included the organization of labor unions, progressive populist groups, the Women’s Suffrage Movement, and a myriad of other developments. The political tapestry is simply too rich to catalogue in this review. Furthermore, there are fascinating sketches of a wide array of individuals who influenced that era and are followed throughout the book. This is a masterpiece of narrative history, perfectly balanced by analyses and themes that completely absorbed my reading for almost 2 weeks.

I do not think it possible to accurate characterize the richness and nuance of this book. It is an extraordinarily dense intellectual meal – every single page had some reference that I wanted to follow up in specialized sources. The core of the book is about politics and economics; I would have liked more cultural detail, but at 968 pages, it is already too long. The level of the reader is advanced undergraduate; there are many allusions to events and concepts that are not fully explained, which the reader must know. Nonetheless, it serves admirably well as a general picture of the period rather than a narrow academic treatment.