The Christian atheist and his philosophical opponents

Review of The Courtier and The Heretic: Leibniz, Spinoza, and the Fate of God in the Modern World by Matthew Stewart

This book is about the modern divide when purely secular reasoning became possible, indeed inevitable according to Stewart, and the reaction against it set in. Spinoza, the pioneering philosopher, is the “heretic”. The “courtier” is Leibniz, who initiated the conservative backlash. While this is a serious philosophy book that makes rigorous arguments, it is presented in rich historical context, a kind of twin intellectual biography.

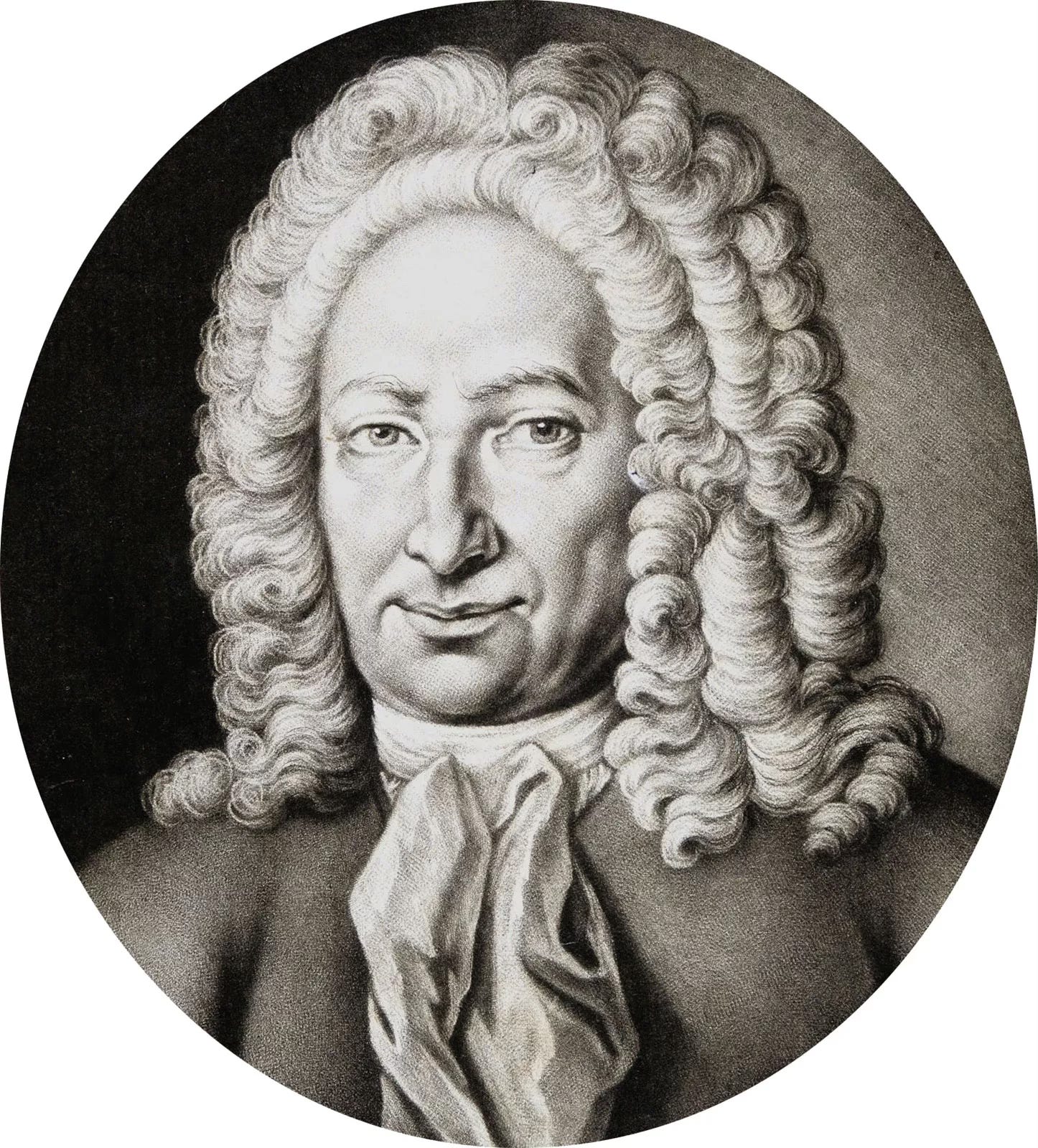

Baruch Spinoza was a “double exile”, a solitary man who lived as a lens grinder and pursued his philosophical interests at night. He was first censured by the Jewish establishment of Amsterdam; instead of repenting his non-conformist views as was customary, he chose to permanently leave the community. This was an extremely bold act in those tribalist times. While the Dutch Republic was relatively tolerant, his views came under official scrutiny and he was forced to move to The Hague, an internal exile that lasted for the rest of his life; he was always under threat of censorship, imprisonment, and perhaps even the death penalty. Though he slowly developed a devoted following, he remained a loner.

The philosophy he developed had a number of unique characteristics. Most important, he argued that God was nature itself, not some anthropomorphic being who was managing everything from moment to moment and imbued the world with purpose. According to this perspective, everything that happened was inevitable, on a set course that no prayer could alter, but in accordance with a divine plan that was there from the moment of creation. In effect, everything was God: to love God was to admire the natural world, which could be understood through rational enquiry. The catch was that nature did not love you back – there was no good or evil, just cold reality and facts, i.e. materialism.

Moreover, in Spinoza’s cosmology, humans lost their special place at the center of the universe and were merely part of nature, entirely subject to its course. While this was viewed as secular, and leading directly to atheism, Spinoza was careful never to apply that term to himself. He was, as my elder child put it, “the first Christian atheist.” His philosophy, Stewart tells us, opened the way to the Enlightenment.

Stewart vividly evokes the atmosphere of the 17th Century. Spinoza’s family was of Portuguese and Spanish origin, prosperous merchants who led conventional lifestyles after their exile in the 16th Century ladino diaspora. He was born in 1732, during the height of the Thirty Years War: in neighboring Germany, Protestants and Catholics were fighting with a murderous brutality that shocked the world. A similar conflict was brewing in Britain’s civil wars. Even the Netherlands was fighting the Eighty Years War for its independence from Spain. In this turmoil, Amsterdam offered the freest publishing industry in Europe, a hotbed of radical ideas and novel ambitions.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was born in Leipzig in 1646, and grew up in the relatively optimistic period following the Thirty Years War, when many hoped that the Catholic and Protestant churches could be reunited as one. While he was a polymath and trained as a lawyer – reputed to be the last man to have mastered all available western knowledge – the principal goal of his philosophical efforts was to bring European thought together into a harmonious whole. In stark contrast to Spinoza’s hermetic lifestyle, Leibniz operated as a courtier in elite European courts, advising princes and demonstrating his “genius” for a fee. For a time, his career was extremely successful and cosmopolitan: he lived in Paris, visited London and Amsterdam as a diplomat and intellectual, always looking for the next posting or opportunity. It is an interesting primer in courtier culture. Unfortunately, during the last 40 years of his life, the best he could do was a counselor position in Hanover, a parochial backwater; among his jobs was to compile a massive genealogical history of the House of Brunswick (which supplied King George I to England in 1714 when Anne, the last Stuart, died without an heir). He lived a frustrated life, sometimes a virtual prisoner forbidden to travel abroad.

Stewart goes into a great deal of turgid detail about Leibniz’s philosophy, or monadology. Much of it is in reaction to Spinoza. So far as I understood it, he argued that the universe is made up of an infinite number of monads, all of which fit together in a whole that was conceived and is actively managed by God. If the course of things is determined by the interaction and characteristics of these monads, an anthropomorphic God ensures that everything is for the good and thus that this is the “best of all possible worlds” (his Theodicy). This is so obscure and flamboyantly optimistic that it is easy to see why Voltaire savagely caricatured Leibniz as Dr. Pangloss in Candide. Aside from Leibniz’s invention of calculus at roughly the same time that Newton did, the rest of his philosophy appears similarly obscure and bound in the recondite controversies of his time – of little relevance to today. The bottom line is that Leibniz strove to refute the materialist implications (read godlessness) of Spinoza.

To dramatize the philosophical rivalry between Leibniz and Spinoza, Stewart makes a great deal of their three-day meeting in The Hague in 1676, when the younger man dared to challenge the older master. I found this a bit contrived, but there is no doubt that for his entire life Leibniz remained obsessed with Spinoza, the “atheist Jew” as he later called him. According to Stewart, Leibniz’s legacy sparked a long line of reaction to Spinoza: what bound everyone in opposition to him was the need for these philosophers to inject meaning into a caring universe – from Leibniz and Kant through Marx and Heidegger. Those on the Spinozian side included Nietzsche and Voltaire.

This is a very fun read, even if I found the philosophical arguments a bit too detailed. Stewart succeeds at vividly bringing both men to life and places their ideas in context.

Related reviews:

The romantic reaction to the hyper-rationalism of the Enlightenment philosophes

Berlin's great themes are the elaboration of the scientific methodology by Enlightenment philosophes and the reaction against them in the Counter-Enlightenment, or Romanticism. In this inspiring series of intellectual portraits of romantic intellectuals, he explores the ways that irrationalism and relativism worked their ways into the political discours…

History of Romanticism, that amorphous movement celebrating darkness, individuality, and wholeness

From the moment that Rousseau rebelled against the Enlightenment – with its assurances that everything could be known and arbitrated by reason – a new and unruly movement emerged. The Romantics would challenge what we can know, how we should study the world and ourselves, and questioned even the precepts of happiness and the "good life". As Blanning pro…

Revolutionary politics between Enlightenment factions and their aftermath

Though the title is a blatant provocation – I guess “failed” is a more marketable title than “partially succeeded” – this is a rich intellectual history. It argues that the “radical” Enlightenment philosophes played a key role in the late 18th century revolutions, losing out to the conservative reaction of the next century. The book is beautifully writt…