The building blocks of pre-Christian religion in sociological perspective

Review of Religion in Human Evolution from the Paleolithic to the Axial Age by Robert N. Bellah

I was brought up atheist, convinced that religion was superstition for the weak. This reflected the views of my father, who left the Seventh-Day Adventist Church in his teens. Our relatives on his side treated us with righteous condescension, assuming their moral superiority as a matter of course, while my dour grandmother despaired of ever meeting us in the afterlife. The whole thing was bewildering. I saw them as blatant hypocrites, preaching brotherly love and spouting racist stereotypes in the next breath, utterly without empathy. Yet I loved my cousins, who I later recognized were struggling with their world view, trying to live up to it, suppressing vague doubts. Slowly, I began to wonder what religion is, where it came from, how it had shaped so many lives. This set me on a long journey into the history of Christianity and ancient religions.

Not only is Religion in Human Evolution a cutting-edge book on the sociology of early religion, it is also a magnum opus capping the long career of Robert Bellah. There is an astonishing density of ideas. Its method is socio-historical, with long examinations of a variety of cultures that are interesting in themselves, but the emphasis is on theory. Religion, Bellah writes, is a system of beliefs and sacred practices that unite adherents into a moral community. What follows is my attempt to sketch the logical argument at the core of his book.

Bellah begins with an introduction to the sociological notion of religion. Simply put, religion contrasts the concerns of daily life (anxieties, practical considerations) with otherworldliness. In the everyday, he explains, philosophically there is a separateness between subject and object, that is, between things we might want to manipulate or use, while our inner self remains isolated. By contrast, in the world beyond, there is a union of subject and object, a wholeness beyond question, a separate reality that is self-contained. Without “beyonding” (imagining or experiencing religious certainty in that separate realm), as he puts it, we feel trapped and alienated in our everyday lives. This is a key philosophical assumption that works its way out in the rest of the book. I must admit: I find it difficult to comprehend fully.

According to Bellah, modes of religious representation tend to be: Unitive, as in an event of such importance – of collective effervescence, with the self “carried away” by some external power – that it stands alone and must be captured in some form. This would include the beyonding he references. Enactive, whereby adherents bow, kneel, eat. It is a kind of extension of one’s own body, lived rather than thought, an action that must carried out in ritual rather than explained. Symbolic in that it stands for something, allowing participation and interaction in what it represents and what its purpose is. Conceptual, a philosophy as expressed in verbal reflection or argument, whether oral or written. Narrative is crucially important here, as a coherent story of the whole, the heart of one’s own religious identity.

Bellah then goes to more general theoretical considerations about human contact and communication, the capabilities that enable us to form groupings. Empathy and love, he says, form the bases of social bonding in humans. We are altricial, requiring adults to care for our children over long periods. Together, they lead to the emergence of “emotional modernity”, as defined by a capacity to relate to others.

Our capacity to think, he continues, comes in freedom from instinctual controls, implying free will and the choice of group cultural development. Deeper biological drives and programming can be influenced by culture, though not eliminated. Finally, sharing thoughts leads to the collective development of survival strategies and skills, a complement to relating to others. Working together represents, he argues, the pre-condition for the formation of early religions.

In addition, Bellah informs us, play (as an activity with beginning and end) is crucially important to the development of religious ritual. Play consists of an alternative reality that is pursued for own sake. Play uses structural and temporal differences that employ behaviors from life but without our usual survival or status aims, hence are not “serious”, but at a remove from everyday life. There are also repeated performances in a relaxed field, free from the stresses of everyday life. Play can be locomotive or movement-oriented, social, or using objects, such as a ball. It enables us to engage in more relaxed selection processes; to maintain and refine capabilities (physical, behavioral); to innovate and create. Its precise opposite is work, not simply normal life. Ritual in this scheme is a serious form of play, a sacred celebration.

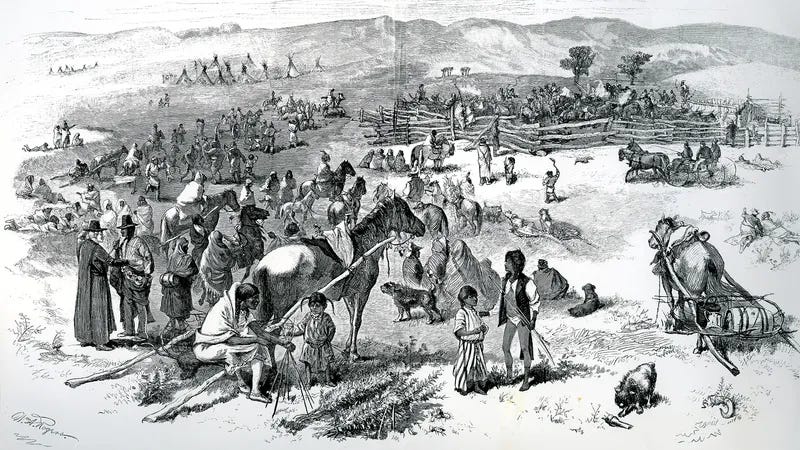

The historical section, at about 2/3 of the remaining book, is less conceptually dense. Hunter-gather societies were relatively non-hierarchical, egalitarian, and had a “sharing” culture. Dissenting upstarts were ridiculed, shunned, then if they refused to conform, killed or exiled, which, Bellah argues, represented an early form of a moral community. Lives were lived in the present, episodically, as a series of concrete episodes with little thought of the past or future. Hunter-gather cultural communication was mimetic and gestural: they acted out sequences of events to teach as well as a rehearsal to develop skills.

Hunter-gather mythical thought involved causal explanation; it represented a means of exploration as well as an attempt to control nature and a reference frame to comprehend the world with conceptual clarity; and finally, it was homiletic, transmitting moral lessons without any explicit religious ethic. Hunter-gather ritual was closely related to, and usually embedded in, myth. Performing them emphasized a connection to powerful beings or forces, a sense of a sacred relation to cosmos. Participation by everyone represented a communal commitment to future action and solidarity. Not necessarily gods, supernatural beings existed on a continuum with ancestors and the forces of nature.

After the agricultural revolution, tribal societies arose that became much larger and more stratified. With dependable food surpluses beyond what a single household could produce, communal groups found it possible to seek more complex meanings over long time frames. An elite emerged, seeking domination and creating a kinship hierarchy, perhaps as despotism, as they took on more complex tasks in the management of nature and security.

Because inevitably the dominant class was resented, some form of legitimacy had to be constantly renegotiated by those who wished to participate in, and gain access to, community resources. This, Bellah argues, was reflected in religious practices. Gods were identified explicitly for the first time; the chief acted as high priest, communicating with them in ritual, often without the direct participation of the community, yet nonetheless channeling and distributing the Gods’ (hence the elite’s) benevolence. Society was a fragile achievement and legitimacy, cosmic and mundane, was easily lost. If this elite failed to endow the community with prosperity and safety, they were out - someone else would be anointed to manage the Gods.

As mass urbanization took hold, “archaic” societies emerged in the form of territorial states, an early form of “civilization” according to which hierarchy replaced kinship as the basic principle of governance. It was at this time that writing arose as an elite tool of accounting and as a mean to record sacred texts for a professional priesthood. Monumental architecture was built as homage to the gods. Mass production was invented. At this time, kingship and divinity fused into a continuum, as the worship of Gods served as an instrument of power; the king was the chosen steward of the Gods, a quasi-divine intermediary who guaranteed life, peace, fertility, etc. As administrators organizing village farmers and seeking taxes, their responsibilities tended to extend to nurturance, justice, and even rudimentary codes of law. As states grew, the application of religion extended itself to multiple ethnicities under the state (Egypt), claiming some universality in many cases (Mesopotamia). Participants in ritual were limited to the elite, which commoners could witness but not join directly, i.e. it was a means of control.

At this point, Bellah gets into the “axial breakthrough” (ca. 600 BCE), his controversial academic claim that many do not accept as a dominant historical trend. The axial breakthrough was, he asserts, the emergence of a “theoretic culture” in dialogue with mythic culture, whose ambition was to build a comprehensive model of the human universe, applicable to all rather than merely to one’s tribe or state. It appeared, he observes, not in big states with dominant priesthoods or entrenched bureaucracies, but in peripheral states with complex, relatively open political systems under severe stress. Itinerant intellectuals circulated, asking vexing questions about the “cosmological/supernatural” and fusing nature and society into a logically rigorous discussion, to the irritation of traditional authorities who did not want to be questioned.

According to Bellah, axial ideas were written into canonical texts to evaluate and discuss in detail, unlike the narrative myths and poetry of earlier eras. Axial themes concerned themselves with greater purity, justice, and new models of reality, and even with one’s own assumptions – it was thinking about thinking (of “second order”). Most important, it displayed a fuller self-awareness and empathy for others unlike oneself.

The rest of the book is an elaboration of examples to illustrate Bellah’s ideas about the axial breakthrough. Most interesting were the examples of Rabbinic Judaism and the Socratic Revolution. During the Assyrian exile, in which their archaic territorial state was destroyed, Israelites created a version of religious resistance: their king might be a subordinate vassal, but they had an independent covenant directly with the one true God, as developed in Deuteronomy. This meant Israeli society was founded not on the rule of man, but through this covenant with Yahweh, a kind of contract: punishments for disobedience could be severe, but it was also an exhortation to teach and inspire by example. Though literary and not in the form of properly logical argumentation, the early Jewish written tradition was heavy on interpretation of the will of God and the exegesis of canonical texts, which were portable during exile; all you needed was a quorum and rabbi to worship. This narrative theology was flexible and intellectually rich enough to have a major impact through the later developments of Christianity and Islam.

Classical Greece reached its own turning point, where citizens who identified with their city-states were under pressure from the Persian Empire and then during the Peloponnesian War. Traditional Greek polytheistic myths had been collectively important, but inconsistent and unreliable as a guide to the world. Festivals run by local notables redistributed some wealth, creating solidarity as furnishers and providers of justice, but their powers were revealed as extremely limited.

Following Xenophanes (the first to criticize the Olympian Gods), Plato wanted to replace Homer and the epics, to make Socrates the teacher of Greece as portrayed in his dialogues. Unlike the then-contemporary sophists (rhetoricians who cynically claimed they could answer any question to the benefit of those who hired them), Socrates admitted he knew nothing and set out to prove that others didn’t as well – he was a seeker of wisdom, not its purveyor. This laid, in secular perspective, the foundations of what became both modern philosophy and later the social sciences. Aristotle built on Plato, writing much of the first truly analytical philosophy. These legacies survived the political collapse of the Poleis system under Alexander and later, Rome.

The other 2 cultures examined – Confucian China and the India of Buddha – were far less engaging in my opinion. Both brought about the questioning of their societies and the conduct of their leaders and dominant social groups. Both purported to advance universal ethical values and to promote justice and proper conduct. These chapters are much more difficult to follow, perhaps because of my lack of a firm knowledge of them.

Bellah concludes that axial theory has 2 senses. On the one hand, it formulated utopian visions that were both religious and political. Though results in the real world were always disappointing, they led to the creation of religious institutions to keep the vision alive, sheltering the adherents in relative safety; their rituals provided a link to the sacred. Second, it advanced disengaged inquiry of universal application to all peoples, regardless of the societal form or who was in power, in canonical writings that led to discussions that have lasted thousands of years - their arguments over the meaning of events served to invent explanations to explain the failures of the Gods to meet our expectations. We still suffer, but at least we do so together.

Bellah concludes with a call for tolerance, understanding religions on their own terms in a way that appreciates them without judgment or biased comparisons. With the exception of dogmatic fundamentalists, no one can disagree with that.

Though often fascinating, this is a massive and difficult book, at the high undergraduate level. It is for the most part well written, but there are many sections of awkward prose and turgid details that appear irrelevant to the main thrust of the book. At its best, it is a dialogue with a great mind, who reviews crucial periods of early history in sociological perspective. To be honest, I do not have the knowledge required to evaluate his ideas in any academic sense, however much it rings true to me. Bellah’s explanation is secular rather than doctrinal - axial, if you will.

Related reviews:

The Axial moment: from tribes to brotherhood

If you enjoyed Gore Vidal's Creation but wanted a more academic grounding, this is the right book for you. The book covers the foundations of four distinct traditions of the "Axial" age: judeism/monotheism, confucianism/daoism, buddhism/yogic meditation, and Greek rational philosophy. Armstrong's central idea is that all four have a common goal, that is…

The birth pains of the first states in all their brutishness and oppression

Scott sets out to demolish the myths that surround the founding of the state, i.e. that it represented progress and longed-for stability, was a natural outgrowth of agriculture, and improved the living standards of its subjects as in a contract with power. Though I am not surprised that the establishment of the first states was a rough process, Scott pr…

We need to look at alternative societies to understand the range of human potential

Traditionally, scholars of “human nature” have focused on 2 opposing poles. Rousseau portrayed hunter-gatherers as existing in a state of childlike innocence, intellectually inferior but peaceful and without hierarchy. In his narrative, the agricultural revolution ruined this egalitarian paradise, introducing social class, inequality, and debilitating n…

How God has shown the way, particularly when the needs of our society change

Robert Wright likes to take on the big questions. In this book, he looks at God, or rather, how God has evolved in the minds (and political institutions) of men. There are a few basic ideas he wants to get across. First, he explores how the conception of God – as wrathful and intolerant or as promoting universal brotherhood, etc. – evolved in response t…

I wonder how this fits into "Terror Management Theory" which posits that our species' knowledge of the inevitability of our own deaths has driven us to either believe in an afterlife or to give our deaths or hardships "meaning"-which often involves being "remembered".

The concept of the inner self being isolated is something I've run into but have never really grasped in practical terms. One of my two therapists was a former Roman Catholic priest (he was forced to leave when he came out as gay), and he sometimes talked about how the "worst thing" was to feel "isolated from God"-something which never concerned me during MY bouts with depression. Perhaps the idea of a "universal" reason for religion is looking for something that doesn't exist. "Transcendence" is another motivation. but again I'm not sure that it's really universal.

Though I was raised in liberal versions of the Methodist and Presbyterian churches (and was even "born again" once or twice) Christianity never "took" with me, and a large part of the reason is its strong reliance on metaphor (the same reason I get impatient with poetry), but along with that there is the "ransom" theory of "atonement" ("Jesus died for our sins"), and "original sin".