The basics on Sparta

Review of The Spartans: An Epic History by Paul Cartledge

The history of Sparta starts with Lycurgus, a semi-mythic law giver who is credited with setting up a uniquely militaristic state around 8th century BCE. First, all the conquered peoples in the surrounding area were essentially slaves (Helots) to the Spartan elite. Not only did they carry out all menial tasks, freeing both men and women to pursue martial excellence, but they served as infantry cannon fodder (hoplites). Second, from the age of 7, Spartan boys were trained in the Agoge, a kind of survival school that was designed to toughen them up; they were supposed to find ways to eat by stealing and not get caught, spent their time training and fighting, enduring pain, etc. Third, by the age of 18, they were farmed out to mentors for advanced training, who they also served with sex. Fourth, once they came of age, they applied to a communal eating group, to which they must be accepting unanimously; these groups were like fraternities, but also competed with each other. If anyone failed to be accepted into one or was kicked out, he lost almost all status and was called an inferior. Fifth, women were expected to participate. Unlike in all other Greek city states, Spartan women were educated, could own property and pass it on as inheritance, and directly contributed to decision-making. They could even take on lovers when men were on campaign without placing themselves in legal jeopardy.

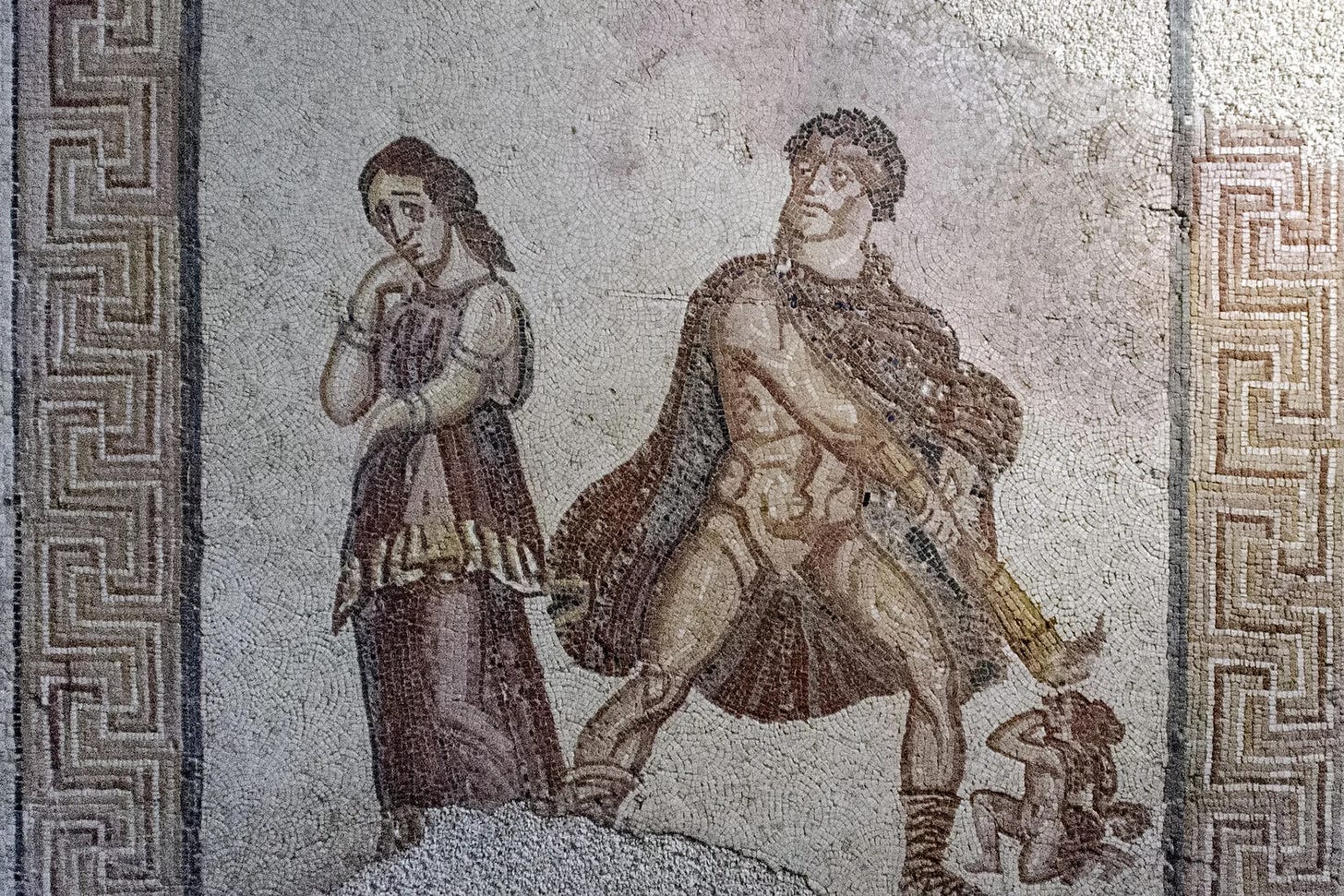

As strange as it may sound, this created a fighting machine without equal from about the 6th to the 3rd century BCE. At that time, Greece was organized into hundreds of city states, which perpetually waged small wars against each other for parochial gain and prestige. The Spartans were superior because they were organized as professionals rather than amateurs who doubled as farmers and estate managers. Supported by a large group of slaves in contiguous areas, their sole business was warfare. In terms of their mythological propaganda, the Spartan Kings claimed to have descended from Herakles.

There were bigger empires in the neighborhood, namely the Persians. When they attempted to conquer Greece, most of the important city states united and a force under Sparta's king, Leonidas, delayed the Persians just long enough at Thermopylae (480 BCE) for the others to regroup and beat them back at Salamis. The other power that emerged was Athens, which headed up the Delian League in the 50-year aftermath of the Persian wars, leading to the era of Perikles. Soon, Athens and Sparta were at each others' throats, which brought nearly all of the Greek city states onto one side or another. After 27 years of war (431-404 BCE), Athens lost. Both states were so depleted that their time as great military powers was done. Other states had learned Spartan fighting methods and so Thebes and then Macedonia emerged as the new powers.

Of course, the bases for Spartan power had also been in decline for decades. Their elite fighting force was too small for the larger wars that were coming, it took too long to replenish the losses of the elite warriors, even if they were unequaled in hand-to-hand combat. They also eschewed certain fighting techniques, such as the use of archers, which they thought "effeminate". Their conceit of never building a fortress to protect their capital city – they said their men would serve as their walls – proved a deadly mistake once they were weaker and under siege. Their slaves also revolted often, a constant threat to the foundation of their state, further depleting resources. Finally, in the battle of Leuctra (371 BCE), Sparta suffered a catastrophic defeat from which it never recovered, shattering its reputation for invincibility; Thebes then emerged as the dominant power of Greece. Soon Alexander of Macedon, after his father, created the vast Empire that was split into the Hellenistic states. Rome became the great Mediterranean power soon thereafter.

The book covers many of the personalities in frustratingly sparse detail. A narrative never really develops and the story is presented less as a chronological progression than as a series of topical essays. Hence, contrary to the subtitle, the book is not as an “epic” – it is an analysis. You get a chapter on religion, a historiography of Leonidas (too cursory to be of much interest), etc. It comes off as disjointed and often somewhat dull, though the prose is not too bad. Unfortunately, the wider context of the times is only vaguely referenced, i.e. a lot of knowledge is assumed. For example, the author mentions the Hellenistic Empires, but does not explain who was who and where they were. If the reader does not know about this at the undergraduate level, the text will be difficult, even turgid.

As a history enthusiast, I was hoping for a popular narrative that would serve as a reminder and update of what I once studied. Instead, what I got was a rather dry academic treatment with virtually no narrative, minimal references to related events, if good coverage of the basics. It is more of a slog than a fun read, but there are many interesting nuggets to be found throughout.

Why were they always fighting until they were defeated? Sounds so contemporary-- a psychosocial analysis would be interesting.