Taiping, that murderous Christian offshoot

Review of God's Chinese Son: The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom of Hong Xiuquan by Jonathan Spence

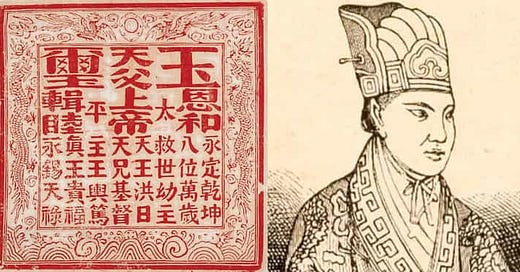

Hong Xiuquan (1814-1864) raised a rebellion in mid-19th century southern China. It was based on his own version of Christianity: he claimed to be a Moses-like figure who knew God and was the younger brother of Jesus. Not only did he find hundreds of thousands of willing converts, but he led an army and established a mini-state in which he reigned as absolute king for a decade. His movement, the Taiping Rebellion, led directly to the deaths of some 10 million. I have long been fascinated by this bizarre episode, in no small part because it occurred in the generation prior to the birth of my grandparents in nearby Canton. Spence’s book is a near-perfect narrative history to understand it.

Hong started out as a typical aspirant to the imperial bureaucracy, attempting to pass the entry-level exams multiple times in his early 20s. After his third failure in 1837, he had a breakdown, became deathly ill, and entered into a hallucinatory or miraculous state, gaining entry to heaven and communing with God, Jesus, and a variety of other prophets. Upon awakening, his family feared he had gone insane. He took up a lowly teaching position and got on with his life. In 1843, he failed the exams for the fourth time. Soon thereafter, he found some pamphlets and a crude, early translation of the Bible into Chinese and upon reading them, began to proselytize.

This is where it gets really interesting. Knowing the classical forms and local religious traditions, Hong could express his views in ways that spoke directly to the Southern Chinese. He could even deal with local potentates, arguing in legalistic terms and language and in accordance with recent international treaties that supposedly granted freedom to disseminate his views. This worked for a time, but he increasingly went against Confucianism (the basis for the Imperial Exams system) and finally the Qing Emperor himself. At the right moment, he went into hiding, initiating a military-scale rebellion.

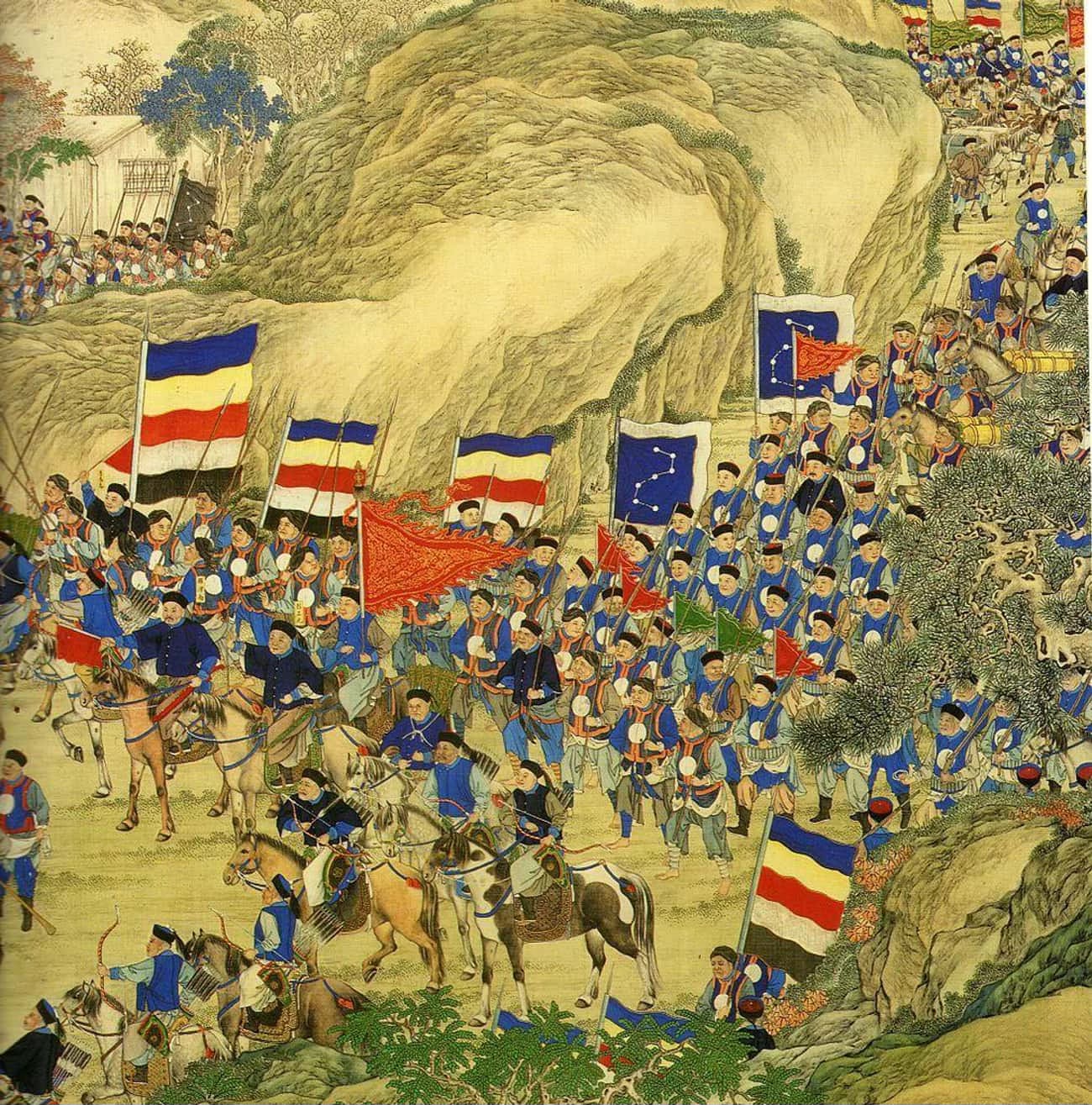

Perhaps due to his charisma and their zeal, from 1851 Hong's forces quickly racked up a number of military victories against the already weakened state, which was reeling from humiliating assaults by foreign powers, the opium war, and escalating brigandage, particularly in the south. Soon, they controlled a vast swath of territory, settling in Nanjing as their “heavenly capitol”. Hong created his own dynasty, often expelling traditional officials and installing his family members or the proven faithful. It was similar to the Imperial forms of hierarchy, but buttressed by religious fanaticism.

In the meantime, courtiers and rivals emerged. Xiao Chaogui began to speak in trances, as the voice of Jesus, directly to the faithful. He soon fell in military action and was replaced by Yang Xiuqing, who claimed to be speaking directly with the voice of God himself. Yang soon came to challenge Hong, establishing a network of spies to report dissension and doubts, doling out orders and judgments based on his visions. Hong was coy, but ended up ordering Yang’s murder and those of his 6000 top followers, who had congregated to watch the punishments of one of his lieutenants. It was a killing field, perhaps similar to that of Kurtz as portrayed in Apocalypse Now. Hong never refuted Yang's visions.

In an attempt to elaborate his theology, Hong consulted a number of European missionaries. It appears that he developed a variant of Arianism, whereby Jesus is not divine but still the son of God. He also edited his own version of the Bible, omitting offending passages and formulating his own, different set of 10 commandments. He went very deep into Christology.

Meanwhile, with Hong's forces divided, the Qing begin to rally and it quickly became a contest of the gifted amateurs against the hardened and experienced professional corps of the Emperor. Slowly but surely, Hong's forces were whittled away, leading to a catastrophic final confrontation at Nanjing. Hong had died, apparently of natural causes in 1864, and his 15-year old son was on the throne for the apocalyptic slaughter of the faithful.

The reader should be aware that this book offers only a minimum of the context that is available in Spence's other masterwork, In Search of Modern China. I wanted more, though fortunately I was acquainted with much of the history. Nonetheless, this is not just an academic history, it is a unique literary event. Though a traditional historian, Spence is a master stylist. This is one of the most brilliant and fascinating narratives of a historical moment that I have ever read.