Strong on political snapshot, weaker on the economic causes

Review of The Age of Austerity: How Scarcity Will Remake American Politics by Thomas Byrne Edsall

With the 2008 economic crisis, the polarization of American politics seemed to have reached a nadar: the political process was stalled at an impasse, perhaps a dead end. Even our political institutions, unable to facilitate compromise and negotiation, may be breaking down. Whoever wins the presidential election, we are told, will face the same, if not worse, polarization. (We now know, it was worse.) In this fascinating and useful book, Edsall attempts to explain why we find ourselves in this situation, what its implications are, and what we might reasonably expect.

His ideas are simple and straightforward: when we prosper, we think of others and are willing to help them; when we aren't, we don't. This explains, he argues, the direction that each party is taking. In one of the best sections of the book, Edsall looks at the "psychology" behind each of these ideological preferences. Democrats represent empathy as well as community-based solutions that involve the sharing of resources; they see society and the economy as having the ability to take many possible forms, the shape of which politicians essentially control; they are open to new ideas and optimistic. In contrast, traditional Republicans see individual responsibility as the key not only to prosperity, but to the moral development of individuals and hence, society; they put their faith in the "free market" as the most efficient arbiter of economic activity, viewing government actions as destructive interference; they tended to be closed to new ideas and deeply pessimistic. As this was written pre-2016 populism, the book is dated.

The heyday of liberal politics, in his view, coincided with the post-war boom years, up until the early 1970s, when productivity was rising and everyone benefitted. Politics was a positive-sum game. Once this golden age was over, the political process of dividing up resources became a zero-sum game: what one person got, another lost – the economic pie was no longer expanding but static. This signaled the time of conservative ascendancy, which has lasted to the present day.

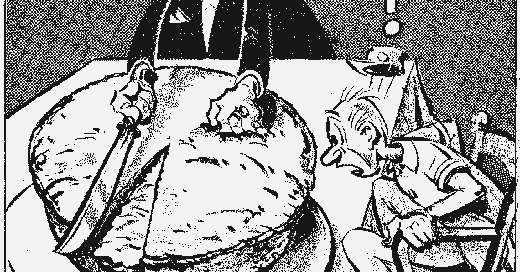

In policy terms, this translated into a fight to gain resources for the natural constituencies of each party. The GOP fought to channel resources to the haves, i.e. the white middle and upper classes. This came at the direct expense of core democratic constituencies: people of color, the disadvantaged, unionized workers, and the educated liberal elites, who believed in a more egalitarian or socio-democratic vision for society. Moreover, the political rhetoric of the GOP – to get ahead by keeping the fruits of one's labor – appealed to many in the lower strata of society, ending the New Deal coalition by pealing off working whites: they preferred lower taxes to government programs to benefit others. To express this in political campaigns, the GOP attempts to split independent voters with attacks on racial preferences, immigrant rights, and the needy, all of whom are portrayed as moochers, i.e. the 47% that Romney referred to in the infamous tape. Indeed, given the frame of the 2012 electoral debate – how to control spending and balance the budget – the conservatives essentially won.

In my opinion, there is a great deal of truth to this line of reasoning. Edsall articulates it very well and backs it up with a huge amount of polling data. So far, so good, but this is nothing new.

Unfortunately, the book comes up short on the economics behind all of this, on the deeper causes and what to do about them. He does cover some structural problems, such as the strain that retiring baby boomers will place on Social Security and Medicare. But there is much more that Edsall barely mentions.

First, the end of productivity rises in 1973 came at the moment that oil prices went up. Without cheap energy, other factors in the industrial economy came to the fore, in particular the cost of labor, sending manufacturing jobs overseas.

Second, with the level of prosperity we reached – virtually everyone had cars, TV, and soon, a personal computer – there were no longer any discernible basic engines to drive economic growth via demand. In my opinion, the hunger for unfulfilled consumer desires explains the dynamism we are seeing in many developing economies, especially in Asia.

Third, to maintain the appearance of growth and increasing wealth, the western economies turned to financial leveraging, i.e. extending credit by allowing banks to lend more with looser financial capital rules. This led to asset inflation as well as enabled the elites to indulge in speculative games in zero-sum betting schemes that tax payers wound up paying for after the 2008 financial meltdown.

Taken together, this means that a slow-growing West may fall behind as other, younger capitalist economies catch up. What should we do about all this? That question is way beyond the scope of the book.

Furthermore, while Edsall strives to strike a non-partisan tone, it is clear that he is a liberal and preferred Obama, though he never states this outright. This will anger many conservatives who read this.