Sprawling, deep and quirky literary interpretation

Review of The Greeks and Greek Civilization by Jacob Burckhardt

Jacob Burckhardt begins with an analysis of how myth may have reflected the basis of prehistorical movements of Greek tribes and families. Thus, the Heraclids – sons of Hercules – were supposed to have conquered the Peloponnese and so were ancestors of the Spartans and others. Then, as the culture consolidated itself to the 7th century, Burckhardt explains the Polis culture, according to which the glory of the city was a collective responsibility of its inhabitants, a source of pride and identity. This led to great city-states such as Athens, but scores of others as well.

When not fighting wars with each other, competitions for glory took place as the Agon, ranging from the Olympian games to generalist education (paideia) as a way to enhance the standing of the Polis. This is pretty run of the mill stuff and takes up the first 150 pages of Burckhardt's text. It lost me many times and I was on the verge of quitting when he got to the classical age – the 5th century – which is by far the best section in the book. Nonetheless, Burckhardt does advance a radical thesis – that the Greeks were not happy in democracy but extremely pessimistic – which went against the prevailing view of the 19th century that viewed the Greeks as happy at a unique cultural and political moment.

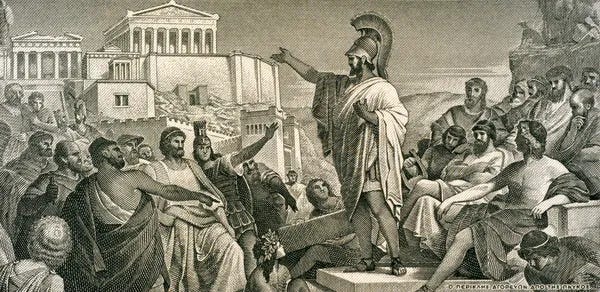

For the 5th century, the reader gets a detailed interpretation of Athens at the height of its glory, after Greece had united to beat back the Persians. Athens set up the Delphian League as an imperialist democracy that took advantage of its allies, taxing them, intimidating them, forcing them to follow Athenian policies. It ended in the tragic war with Sparta. This period – the first with an extensive literature of use to historians – saw the birth of rationalist philosophy, tragic drama, objective history based on multiple sources, and the monumental architectural forms based on the rectangle and circle that dominated the medium until the 20th century. It also saw fundamental experimentation in military and administrative regimes that led not only to Alexander the Great but also was studied by the Romans. There was, in my view, no greater flowering of culture in the history of mankind, with the possible exceptions of certain periods of the Chinese, Islamic, and Indian civilizations, though the latter did not succeed in creating the same linear sense of history that leads us in the West directly back to the Greeks.

Underneath the achievements, Burckhardt uncovers the destructive impulses that underlay much of the creativity: the ruthless ambition, the breakdown of the norms of government and ethics, and the slaughter of rivals both within the Polis and between rival city states. In this period, the ideals of the Polis, democracy, and the Agon were subverted and eventually destroyed, resulting in nostalgia for a "golden age" that was forever gone though preserved in form like a world under the microscope. It is a chilling picture, which led directly to the takeover by the Macedonians, who transmitted much of the culture without its creative vitality throughout the Mediterranean and beyond.

I learned a great deal from this book, indeed I pictured the wholeness of the classical Greek cultural arc in a way I never had before. However, reading this is very challenging. It is not an introductory text. The reader must persevere through many dry and obscure passages, with references that require one to have an encyclopedia at hand. Some of it is out of date – you get no archeology at all as its sources are entirely literary, hence slanted to the concerns expressed by the elite of that time and interpreted by 19th century CE Swiss bourgeoisie. The reading experience is not helped by the turgid 50-page introduction by the editor, who places Burckhardt (the founder of Kulturgeschicte, where "ideas are in the air") in opposition to the exceedingly pedantic 19th century historical style of knowing more and more about less and less.

This book is taken from a series of lectures and was not intended for publication as a book. It assumes that the reader had a classical education as was traditional in the 19th century CE, that is, studying the languages and literature from an early age all the way through high school. That was a time when not only the most famous characters and myths were known as a common vocabulary, but were referred to regularly in popular culture (poems, operas, paintings, etc.). The reader of the 20th century might know who Pericles, Socrates, and Solon were, but it would take a classics major or serious history buff to know the names Alcibiades, Cleon, Lycurgus or the hundreds of others referred to with regularity. This text more or less assumes the reader has this culture and offers a subtle and deeply satisfying interpretation of how they fit into a coherent, yet eclectic culture that informs the basis of much of modern European culture, but it does not retell the essential stories or even the basic history.

Related reviews:

A flowing narrative on the Persian Empire

This book is about the collision of 3 worlds. First, you have the Persian Empire, the first multi-national fighting force that sought to exploit (and to a degree, respect) the attributes of its innumerable ethnic groups rather than impose the domination of one on them by force. This was the work of Cyrus the Great, who transformed a mountain nomad tribe…

Review of Alexander of Macedon, 356–323 B.C by Peter Green

Alexander the Great provokes interpretations that tell as much about the interpreter as about the man himself. Was he an incipient humanist, spreading the values of Hellenistic culture? Was he a cynical totalitarian autocrat, using propaganda and words when it suited him? While admittedly a military genius, was he a megalomaniac who became progressively…

Birth of the "west"

This book, which covers one of the most remarkable eras in the history of mankind, attempts to be both scholarly and literary/popular. Unfortunately, while the content of it is utterly fascinating, the way it is written – or perhaps translated – leaves much to be desired: the style is flat and dull, frequently unclear, and simply a chore to plod through.

Review of Alexander to Actium – the Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age by Peter Green

Kulturgeschichte is a 360-degree portrait of the “ideas in the air” in a given historical moment and culture. It is supposed to be scientific, a complete explanation bringing together economic, social, and intellectual movements. This is what Peter Green hopes to do for the Hellenistic Age, the empires that sprung up in the wake of Alexander the Great's…