Riveting narrative on greed, subjugation, and despoliation

Review of The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company by William Dalrymple

This is a book about the ultimate prototype for corporate greed, the first joint-stock company that conquered and plundered an entire subcontinent. It is not about economics or business, but about private empire-building, virtually without constraint, with shareholder profit as the principal motive. Along the way, the East India Company attacked with superior technology, played warring factions off one another, set up an economic system that coopted the Bengali banking class, and even developed a few administrators who actually cared for the country itself in a relatively benevolent manner. Members of the British Parliament also attempted some oversight, though the company enjoyed a free hand for over a century. The story is simply astonishing, full of larger-than-life characters, daring exploits, and cruelties beyond imagination. A phenomenal read about a time that has never really vanished.

The East India Company was incorporated in 1600. It was a small, unprofitable trading company in a country that was a minor power, with a weak navy, small population, and few natural resources. Spain, Portugal and Holland had already craved out colonial possessions, leaving little room for England. Nonetheless, with a few hundred soldiers, the Company negotiated trading rights in Calcutta with the Mughal Emperor, who operated from one of the richest cities in the world, Delhi. He regarded Britain with disdain and condescension.

At that time, attacks from Persia (the warlord Nader Shah) and Hindu regions of India (various Maratha warlords) were altering the balance of power in a series of catastrophic setbacks for the Mughal Empire, eventually undermining its power and authority. Suddenly, the Company was regarded as a potential ally. This was right at the start of a period of anarchy, which lasted more than 50 years. Later, an unstable adventurer, Robert Clive, racked up a number of military victories against the Mughal Emperor, gaining territory and time for the Company to train Indian troops (Sepoys) in European tactics; Bengali bankers were happy to finance their training. With unprecedented war booty and rewards, Clive became one of the richest men in Britain.

The Company was soon a major player in eastern India. Not only did it have to fight enemies of the Mughals, but rival European powers, in particular France. Suddenly, India became a place to make careers and fortunes for penniless second sons and disenfranchised Scottish highlanders. In addition, a number of ruthless and highly competent military commanders came to India; they included Cornwall, who had recently lost the Revolutionary War to George Washington, but also the Wellesley brothers, the younger of whom would become Lord Wellington. They eventually dominated all of India and ended the Anarchy, using local leaders for routine administrative tasks but ruling directly for purposes of profitmaking. Cornwall set up a clever system of land taxation that favored the Bengali bankers, gaining their allegiance – crucial considering the company depended on them for injections of capital through debt. They transformed India into its modern form, in effect destroying the civilization that, if decadent and in upheaval, had evolved on its own over centuries.

There is a great deal about intra-Indian violence, which can only be described as exotically horrific. Gouging eyes, annihilating entire royal lineages, tortures, downfalls and resurrections, alliances and spectacular betrayals and the like. The bottom line is that Indian leaders could never unite to expel the Company, but continued to jockey for advantage until there was no one left. The treatment of puppet princes is described in great detail.

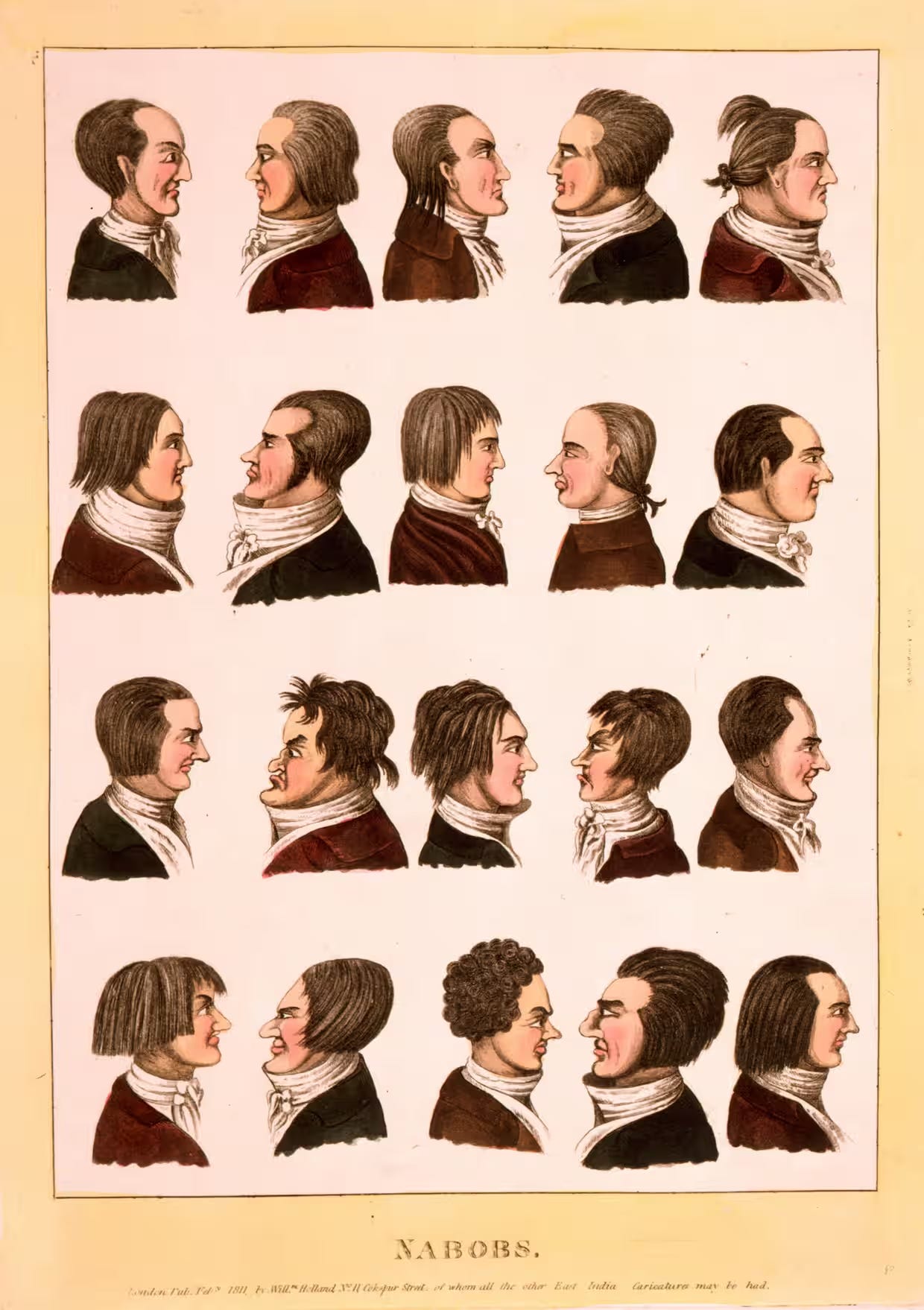

After viciously and blatantly looting the treasury of the Mughal Emperor, the company presided over a horrendous famine in Bengal. Caused by a years-long draught, up to one third of the rural population starved. While some measures to alleviate the crisis were taken by Warren Hastings (British colonial administrator, chief of the Nabobs), many other employees hoarded grain for profit. Needless to say, the famine reduced Company revenues, pushing it to the verge of bankruptcy; because it accounted for over 25% of trade tariffs in the UK – absolutely vital for state finances – Parliament funded the largest bailout in corporate history.

Dalrymple also covers the long impeachment trial of Warren Hastings for looting and corruption, in which none other than Edmund Burke was a prosecutor. Interestingly, Dalrymple portrays Hastings as something of a progressive acting in favor of India, attempting to instill better behavior. Though Hastings was acquitted, it was one of the first trials in which a powerful corporation was called to account by a government.

While the narrative is consistently excellent, I would have liked more about how the company operated, what it contributed to the development of Britain itself, and such details as the manner in which the notion of a shareholder multinational corporation developed. If readers want these details, which are mentioned inadvertently, they will need to look elsewhere.

Related reviews:

Grandpa Wagner's beloved Grandmother was the first born out of enslavement. Her parents escaped on the Underground Railroad just prior to the Civil War-- first story I remember being told. I have a picture if you email.

We spent February in Rajastan and Punjab, immersing in the remains of the Mughal culture (especially art). I was hoping to learn more about the Sindhi (close genetic kin of my mom’s Sinti) there, but no luck, since they are mostly dispersed since partition.

Again, I have an ancestor of interest to the British narrative: Richard Jones, Earl Ranelagh managed the British tax system (with some innovations I’ve not studied yet), no doubt related to the Company’s approach (pro or con, I don’t know). Such applied math has been part of the family story since before then— he was Katherine Boyle Jones’s son and Robert Boyle’s nephew.