Our early democratic institutions and society

Review of Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815 (Oxford History of the United States) by Gordon S. Wood

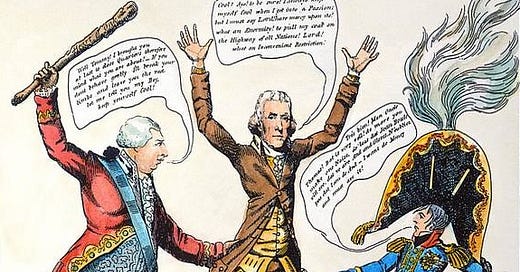

At the start, just after the Constitution was ratified, the Federalists were triumphant (Washington, Hamilton, Adams). Wood defines them as would-be British aristocrats, attempting to set up a social hierarchy similar to the monarchy that the US had just thrown off. To establish their regime, they set up elaborate systems of patronage with the privileged, who were landowners and big businessmen. Their goals, Wood continues, were to create a modern, centralized state – with a banking sector to finance a continental-scale commercial economy, an organized military under the control of the federal government, and a legal apparatus to set national priorities, including taxes. They deeply feared the partisan wrangling that would come if parties formed. By background, they admired the British, entertained Enlightenment ideas about rational discussion, and tended to be "deists" who believed that God had created a mechanistic universe that operated according to discernable rules rather than requiring regular intervention with judgmental intent.

Opposition developed, led first by Jefferson and later by Madison, from their fear of centralized power. Rather than the British, they preferred the French Enlightenment, particularly when revolutionaries threw off the yoke of their monarchy, but also by intellectual preference and lifestyle emulation. Unlike the Federalists seeking to create state power, they wanted the US to remain principally agricultural, a republic of thrifty yeomen, a kind of salt of the earth in their minds. Part of Jefferson's political genius was that he synched with the rising populism of the time, which by enabling more men to participate in politics was anti-aristocratic. This ushered in electoral politics and spawned partisan groupings, known at the time as Jeffersonian Republicans.

In my opinion, the book is not clear enough regarding what exactly each grouping represented. Though the Federalists were pro-business and wanted to set up a national administrative infrastructure to support them, it alienated smaller entrepreneurs and artisans, who saw the Republicans as more supportive of their ambitions. This seemed to me paradoxical, but they voted for Jefferson en masse, permanently eclipsing the Federalists. Wood appears to clearly prefer the Jeffersonians over the Federalists, i.e. a little too accepting of their rhetorical positions at face value. Wood could, I believe, have been far more critical of Jefferson – the guy thought a lot of strange things up and was a hypocrite. His embargo policies against the British, applied with extraordinary ideological zeal, devastated local men of commerce. Clearly, these groupings were not direct ancestors to our modern political parties, as their ideological convictions were re-shuffled in subsequent generations.

Beyond these political wrangles, the social and economic changes underway were legion and fundamental. First, given the rhetoric of liberty, Southern planters developed a racist ideology to explain their need to own slaves (they were inferior human beings incapable of taking care of themselves). This is the fissure that inevitably led to the civil war and underlies the race problem of today.

Second, with the decline of state-supported churches, an unprecedented flourishing of protestant sects began, lasting to the present day – they were democratic (i.e., less authoritarian), offered personal salvation in new ways, and had characters that were genuinely homespun. Some (including Jefferson) believed that the Indians may have been "the lost tribes of Israel", a central tenet of the Mormanism that was established in the next generation.

Third, Americans shifted their attention westward, arguing that they were uniquely distinguished from Europeans and would develop their own culture and mores. This meant not only that they stopped their attempts to copy European cultural accomplishments, but also became self-absorbed and convinced they were somehow special – after the rise of Napoleon they represented the only experiment in republican government, but they also became willfully ignorant of many developments elsewhere, even myopic. Finally, with industrialization, a commercial culture began to dominate the economy, to the extent that even Jefferson admitted his agrarian utopia was unworkable.

I should mention what this book is not. It is not a narrative history with mini-biographies and vivid stories. Instead, it is highly analytic, looking at trends beneath the surface and explaining what they mean. Furthermore, it is not an introductory text that goes over the basics, but assumes knowledge of the main events and important personalities. That makes it an advanced text for, say, undergraduate history majors. It is the perfect stepping off point for interested students who have just suffered through a general text book.

This book is a great intellectual adventure. I came away from it with very clear ideas about long-term trends that originated within the conditions that existed at the time, as American institutions were set in motion in practical ways and the society established its own, uniquely American identity. Though I think he is too hard on the Federalists, Wood never indulges in a triumphalist tone or an overly proud celebration of American uniqueness.

This is one of those books that you can read about a period you think you know well, only to discover a thousand subtleties and surprises, completely and forever changing your perception of the period. I was fascinated by something on every single page of this book, an intimate journey with a true master historian who is writing for a popular, if knowledgeable audience. I did not always agree with his perspective, which made the dialogue all the more stimulating.

Related reviews:

Focusing in on the gravity well of the Founding Fathers

Burr is something of an enigma: clearly a man connected and with a strong following, but he has been vilified as a scoundrel and, in spite of 3 trials, was acquitted of any crime, even as he killed Hamilton in the duel. Roger Kennedy sets out to explain all this by comparing him with his 2 greatest enemies, Jefferson and Hamilton. Rather than straight b…

Review of Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow

Chernow has come under attack for providing near-hagiographic bios of important Americans. If these kinds of vanilla jobs seem typical of some American biographers, I don’t think Chernow is guilty of this. His Alexander Hamilton goes deep into the details of what he accomplished in context, without the obscuring myth or wisdom in hindsight. Chernow is d…

Narrative of the United States in formation

This is a delightful read on that period in US history where the country was massively expanding, defining itself, and dividing into the hardened blocks – regional and ideological – that we can still see today. It begins at the moment that the Federalists imploded and the Republicans, as led by Jefferson, emerged as the new dominant party.