Medieval astronomy, a monk's life and times, and scholastic research

Review of The Light Ages: The Surprising Story of Medieval Science by Seb Falk

I was drawn to this because the first character mentioned is Derek Price, who was a mentor to my mom. He was a quirky and remarkable man who promoted the history of science at Yale, always sticking his nose into something with an aggressive curiosity. In this book, as a student at Cambridge he discovered a manuscript that he believed was written by Chaucer himself, naturally generating publicity for himself as well. Though later proven it was written by an obscure monk, John of Westwyk, it turned out that it was a primer on how to build and operate a scientific device, the equatorium, which improved on the astrolabe as a way to track and predict planetary motion.

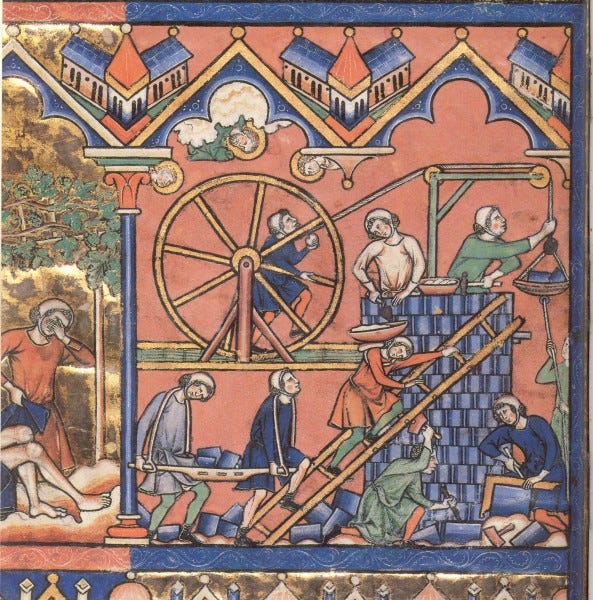

Seb Falk’s book starts off wonderfully, with vivid descriptions of monastic life, how people were thinking, and what they endeavored to accomplish, particularly in “science” (broadly defined as advancing and disseminating knowledge rather than the tightly disciplined empirical method of today). Monks were involved in astronomy not just to understand the cosmic mechanisms that God had created, but also because they felt they were getting closer to his mind and the divine order in a profoundly moral sense - the parameters of their mental categories were far more porous and overlapping than ours today.

There was also a great deal about the founding of the early scholastic universities, Oxford and Cambridge, and what life was like in them. I enjoyed this as well as the many historical details that were elegantly presented. For example, Westwyk was sent to Tynemouth Priory, a ruined monastery about which I had long wondered. Falk goes all the way back to the beginning of the medieval ages to describe the evolution of the place. There are many more instances of this kind of intellectual adventure.

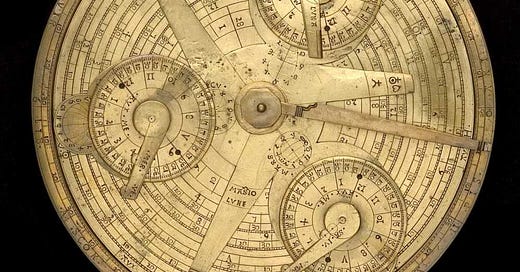

The book gets into some trouble when Falk treats scientific and mathematical detail. Unfortunately, these details are key to the whole point of the book and they are a lugubrious mess of technical questions that I found confusing and needlessly difficult. He begins with the workings of the astrolabe, a measuring device to chart the heavens. While useful for all sorts of calculations, such as the heights of mountains, they were good only at the latitudes for which they were designed. Even worse, with the systemic variations in the rotation of the Earth, they got increasingly out of date; to remedy this, scholars had to produce and update long tables of figures, introducing error and taxing the patience of students. As a result, to improve the study of planetary motion, Westwyk invented the equatorium, a kind of early computer that eliminated the need for accompanying tables. Both devices were, of course, modeled on the Ptolemaic system of orbiting spheres with the Earth at the center of the universe. After much effort, I must admit I am not sure if I truly understood what Falk was trying to convey. Furthermore, I did not like his use of lengthy quotes from Chaucer to evoke the times.

I think it is a mistake to talk of “science” prior to the unique synthesis that was achieved by the Philosophes. The monks clearly were attempting to understand the motions observable in the solar system, but they unwittingly mixed in theological suppositions and astrology; their research was scholastic, an attempt to build a hierarchical edifice of knowledge that was static rather than a dynamic, ever-improving understanding of phenomena. It was only in the Enlightenment that the advance of theory became dependent on independent verification by observation and prediction.

Related:

Breaking the metaphysical impasse

Gay’s ambition with these two books is to describe the Enlightenment mindset and assess how the philosophes’ ideas worked out in the real world. What was new and different about them? How did they change our approach to science, psychology, society, then political science and government? What was their practical impact? If you want answe…

Gothic technological revolution

This is a dense, brief history on how technological change impacted late medieval society. The historical backdrop to the technological revolution takes place from the beginning of the Gothic era, when the Dark Ages had given way to a period of rapid change (1150-1375). This is when stable cities began to flourish in relatively greater safety, vast rang…