Masterful history of a time of great upheaval

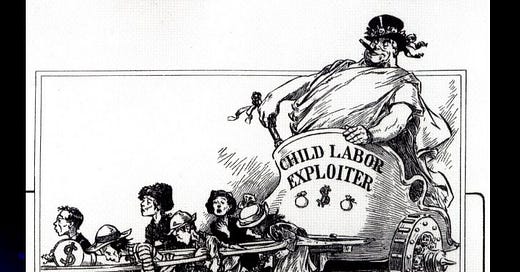

Review of Standing at Armageddon: A Grassroots History of the Progressive Era by Nell Irvin Painter

If you think that the present era is bad, all you need to do is read about the Reconstruction to see America at its absolute worst. This book covers the close of Reconstruction, into what has long been portrayed as an era of explosive "progressivism". It is a kind of people's history as well as covering the actions of leaders. The result is a brilliant …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Crawdaddy’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.