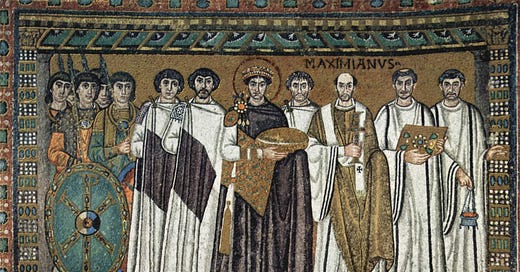

How early Christian theological struggle met imperial politics

Review of Jesus Wars: How Four Patriarchs, Three Queens, and Two Emperors Decided What Christians Would Believe by Philip Jenkins

This book is the perfect follow-on to Ehrman's Lost Christianities, which offered an amazing tableau of the many versions of Christianity that arose in the 2 centuries since Jesus' death. Jenkins starts with the state of theology in the 4th century – the great debate on the nature (or purity) of Christ's divinity – and examines in great detail how it pl…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Crawdaddy’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.