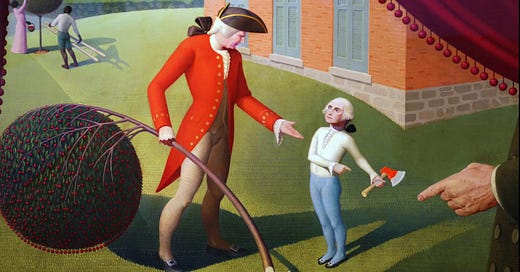

Washington has always seemed somehow inaccessible to me, like an Olympian who rules from the mountain rather than a rough and tumble pol. We Americans have been brought up on so many ridiculous myths, such as the chopped-cherrie-tree-cannot-tell-a-lie story to the neutral presider over the innumerable factions of bickering revolutionaries. While I had read bios of virtually all of his founder contemporaries, I never felt I could penetrate the cloud around him.

Then I discovered this masterful book. Not only does it follow his career, but it informs the reader as to Washington's motivations, emotional life, and methods – he was passionate, ambitious, coldly shrewd, and stringently self-disciplined. (In contrast to his popular image, he had a fiery temper that he learned to keep in check with great difficulty.) In each step of his life, he learned certain lessons from experience rather than books, shaping his attitudes in his own way. Though born to a plantation family, he was relatively underprivileged (i.e., not the prime heir) and so had to make his way more or less on his own. He had little formal education.

First, he found a military career under the British. While he learned a great deal about how to fight on American soil – with different requirements than European theatres – he came to despise aristocratic privilege, which all too often reserved position and advantage to the mediocre and undeserving.

Second, after a tumultuous career beginning – he oversaw a massacre by Indian allies that led indirectly to the Seven Years War and was a key player in many significant defeats – he benefitted from his reputation to make a crucially important marriage to the widow Martha, enabling himself to become a gentleman farmer for 16 years, at the pinnacle of Virginia gentry. However, while maintaining a properly pseudo-aristocratic life style with extremely expensive European goods, he proved to be an innovative business man, with real estate deals and experiments in the management of his estates; because he came to distrust faraway officials dispensing favors and merchants who enmeshed his neighbors in inescapable debt, he moved away from mono-crops such as tobacco, the markets for which were unpredictable, towards self sustainability. This created a streak of fierce independence and self-reliance within him and, alone among the founding fathers, he died a very rich man with minimal debt. When the time came for the revolution, he was ready to risk everything to preserve his political and economic autonomy.

Third, he took over the motley and poorly funded American rebel forces and led them to victory in spite of his early catastrophic defeat in New York, where he concluded that he would have to harass the British to gradually wear them down rather than confront them en masse directly in the field. This long conflict forced him to contend with the incompetent confederation government, which convinced him of the need for a strong executive that had the power to tax and act effectively. As such, this explains very clearly why he sided with the Federalists later. Once again, this was counterintuitive to conventional wisdom: the colonies had revolted against the British monarchy’s policies and taxation.

Fourth, we see the politician emerge at the start of the Constitutional Convention. Washington retired with unsurpassed prestige, so his participation might have ruined his reputation as the country's liberator. He waited a long time to commit himself, weighing his options and getting up to speed on the political vocabulary through tutorials with Madison – while he had some idea of what he wanted to do from his experience as a leader and executive, he relied on his more learned colleagues for the right way to describe and sell it.

Fifth, as president, Washington not only established many of the norms of executive power and practice that have survived intact to the present day, but also attempted to manipulate the political forces to prevent the country from fragmenting into competing adversarial powers. Of course, in hindsight, we know that he failed to forge a durable union by the middle of the 19th century, that the issue of slavery (and the economic system it supported) had to be reckoned with later, though the delay of a few generations may have been enough to keep the union from immediate and permanent disintegration. Nonetheless, Washington essentially created the federal system of government, with its ability to raise funds, maintain an army, take precedence over states' prerogatives, and serve as a decisive economic actor (all of which is still controversial). Here, Hamilton was his indispensable instrument of action – but it was Washington who was the real mastermind. To paraphrase, he attempted to make the United States a singular noun rather than plural. Ellis convincingly portrays the immensity of this undertaking, as the first republic to rule over such a huge and socially disparate country.

Ellis' book is quite brief, so I feared it would be superficial, such as Anthony Everitt's mediocre treatments of Roman pols. Fortunately, Ellis pulls it off with wonderful depth: the book has a density that can only come from a master historian and writer. I implicitly trusted his analyses at every turn and never found his statements glib or tendentious. He is critical of Washington, never makes excuses for his faults, but respectful.

This is a great introduction to an extremely complex and supremely gifted man.