First Romantic, embryonic Totalitarian, radical Democrat, Educator, and eccentric Naturalist

Review of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Restless Genius by Leo Damrosch

Rousseau has always been something of an enigma to me. Self educated, he started his career in music, gravitated to writing both novels and essays, made himself a place in the elite of the Enlightenment only to rebel and alienate just about everyone, ending up paranoid and lonely yet one of the most famous men of letters in Europe. It is an astonishing life and he left a lasting impact, indeed he pioneered many of concepts that are crucial elements of the modern sensibility. Unlike the urbane philosophes, he was rustic and anchored in the nature of the countryside, preferred his own company most of the time, and he flatly rejected many offers of patronage, even from the King of France. No one would own him. Damrosch’s richly textured book goes a long way to explaining how he ticked.

Rousseau was born in Geneva, an independent Protestant oligarchy with extremely strict moral codes and laws. His mother died days after his birth and he was never very close to his father. Though supposedly of noble stock, his family found itself in reduced circumstances. Rejecting a brutal apprenticeship with a watchmaker, he fled to France, to his father’s embarrassment and financial penalty, and converted to Catholicism. His elder brother had disappeared in a similar manner, never to return. Rousseau had no idea what he was going to do with his life and tried variously to work as a valet, a petty thief, and tutor, all with little success. He even took a few months to train for the clergy with a priest, but in the end decided it was not for him. Throughout this period, he experienced a number of traumas, including a homosexual assault that apparently left him fearful of intimate human contact.

Then he got lucky: Mme de Waren, an independent, exiled Swiss aristocrat who had escaped an abusive marriage, took him under her wing. At about the age of 20, he was free to educate himself in music and literature with the leisure and comfort that can feed a young imagination. Mme de Waren was surrogate mother, mentor, and lover all rolled into one. This acquainted him with the courtier life under the Ancien Régime. As he approached 30, de Waren decided to take another young man in, this one with a better business head than Rousseau, who had been alarmed at her failing business schemes. Eventually, he left. This was a pattern he seemed to get himself into for the rest of his life: find an enabler, worship them with incredible devotion and friendship, then quit them, disillusioned and often bitter. Nonetheless, Mdm de Waren was special to him: he felt indebted and sent money to her whenever he could, though she died in poverty. To support himself, he transcribed music by hand, a task that he pursued intermittently and enjoyed for the rest of his life.

Rousseau’s big break came when he was about 30. He composed a one-act opera, Le Devin de Village, that proved immensely popular. It so pleased the King, Louis XV, that he was offered a pension that would have set him up for life. To the astonishment and disgust of his friends, Rousseau balked at accepting it, insulting the King and embarrassing his court contacts. While this may seem unbelievable – such a pension was a coveted honor and guarantee of financial freedom – Rousseau had his reasons: he would be beholden to no master because he couldn’t abide being under someone else’s control or debt. This too would become a lifelong pattern. From this success, Rousseau turned to writing (Letter on French music). He quickly worked himself into Enlightenment circles, including a venue with Diderot, who asked him to write hundreds of articles for his encyclopedia.

At this point, Rousseau introduced a number of explosively innovative ideas. First, in his Discourse on the Origin of Inequality (or The Second Discourse, 1755), he questioned the entire notion of civilization. This flew directly in the face of the dominant Enlightenment narrative, namely, that society could be improved and had been getting more civilized, equal, just, and fair for centuries under enlightened kings and honorable aristocrats (who would do even better if they followed the advice of the philosophes).

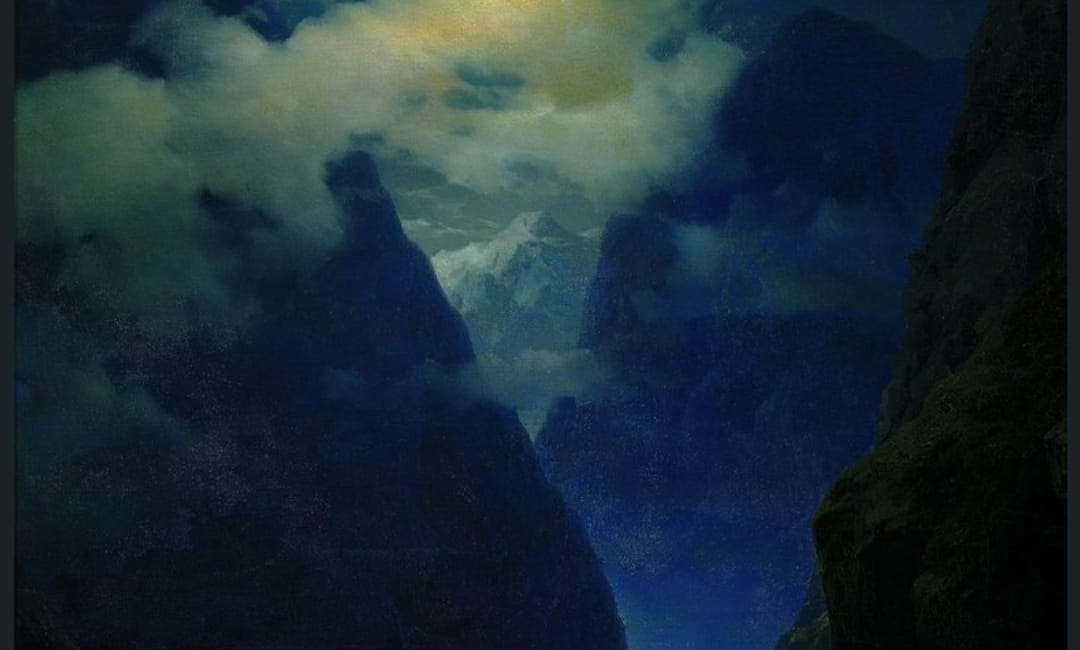

Rousseau disagreed, arguing that man in his “natural state” was far superior to men who lived in society. Though primitive man did not live by reason (another Enlightenment precept), he had a natural sense of justice, self-worth and egalitarianism, however solitary that might have been. He also lived without property, language, or society. In contrast, the advent of civilization created artificial hierarchies of wealth and power, forcing man to compare himself with others and suppress his nature and conform to the strictures of reason, language, and society.

Rousseau’s critique of civilization is one of the foundation stones of modern thought, a radical departure that went against the principal goal of western philosophy since at least the time of Socrates, that is, the search for absolute and immutable truth. Instead, according to Damrosch, Rousseau refers back to a flexible human nature that precedes this kind of talk, that is in a sense beyond its limits. This opened a new way in philosophy that culminated in Nietzsche and the existentialists. If it was in part a reaction to Locke’s Leviathan – that the state and civilization are required to protect men from anarchic violence – Rousseau also incorporated rudimentary social scientific observations. In particular Rousseau relied heavily on the descriptions of colonial contacts with Native Americans, whose societies were organized along different principals, indeed that suggested alternatives to the absolutist monarchies that dominated Europe. In any case, it was the beginning of his break with the philosophes.

Second, in The Social Contract (1762), Rousseau extends his political philosophy to the legitimacy of the state and its rulers. It is his attempt to make political authority compatible with individual freedom. The only way this is possible, he argued, is via a social contract, that is, the rulers are the servants of the people. Not only did this question the legitimacy of absolutist regimes, but it inverted the traditional model of society, according to which the people were subjects rather than citizens with inalienable rights. The people represented sovereignpower, which was separate from government or the state, which exerted an executive power. Though not a radical democrat, Rousseau contributed to the possibility.

Perhaps even more significant, Rousseau argued in favor of an ill-defined collective, or unified, will that society should serve, to which all citizens or members should subordinate their personal desires. Many political philosophers have argued that this was a major step towards totalitarianism.

Third, in his novels, Rousseau explored various aspects of society. In Julie, he wrote a philosophical novel about love and family, virtue and authenticity. More consequential was Emile, which attacked the authoritarian educational system. Rather than a top-down conformance to rules and formula, Rousseau argued, education should be shaped to the individual’s needs and talents. Though he remained a Christian, Rousseau questioned its infallibility. Both of these novels elaborated on the ideas in The Second Discourse and The Social Contract.

Needless to say, these views got Rousseau into trouble with the French and Swiss authorities. Though they were reluctant to create a martyr or even to persecute Rousseau, he was eventually forced to flee from the countries he was living in. He even ended up in Great Britain for a time, where his benefactor was none other than Hume. This peripatetic life seemed to suit him, however difficult it was to pull up roots and flee at short notice. As a recognized great writer, the French authorities for the most part gave him significant leeway, so long as he avoided additional controversies.

Rousseau’s final great literary invention was the autobiography (Confessions), published posthumously, not just to offer moral lessons along Christian lines as was customary, but to explore who he was and what made him that way. What is so pioneering, according to Damrosch, is that he attempted to present himself in all his complexity and mystery, warts and all. This was, in Damrosch’s interpretation, the first genuinely modern attempt at introspection, an antecedent leading directly to psychology and Freud’s unconscious mind.

The autobiography brings us back to his enigmatic character. He was famously quarrelsome, falling out with virtually everyone who befriended him or aided him, often in a virulently paranoid fashion. Damrosch attributes a lot of this to his upbringing, shuffled around as he was and without a consistent intimate father or mother figure. Then there were his sexual proclivities: he got erotic pleasure out of spanking, but apparently was too embarrassed to ask his partners to satisfy this compulsion. He had only a few lovers in his life, was unsure of himself and often felt guilty about sex, and wrote with uncomfortable ease and frequency about his masturbatory practices. He had only a handful of relationships in spite of many opportunities as one of Europe’s most famous writers, settling with a working class woman he loved; notably, they had several illegitimate children, all of whom they gave up for adoption. His last years were spent in suspicion and fear, perhaps mentally ill.

This is one of the best biographies I have read in years. Damrosch covers the life events, but also evokes the context and shows how Rousseau fit into his times. He was perhaps the most important precursor to the romantics, those critics of the Enlightenment who believed that rationality and reason couldn’t explain everything. His was a truly original mind, in spite of the crazy aspects to his personality. The writing is elegant and extremely dense.

Related reviews:

Elegantly argued claim that the Romantics opened a whole new avenue of philosophy

This is a splendidly dense introduction to the Romantic Movement. Berlin argues that the Romantics established a new kind of relativism and possibility, forever demolishing the 2000-year search for absolute certainty in philosophy. When the Romantics emerged, it was at the moment that reason had seemingly reached its apogee in the Enlightenment. With the…

History of Romanticism, that amorphous movement celebrating darkness, individuality, and wholeness

From the moment that Rousseau rebelled against the Enlightenment – with its assurances that everything could be known and arbitrated by reason – a new and unruly movement emerged. The Romantics would challenge what we can know, how we should study the world and ourselves, and questioned even the precepts of happiness and the "good life". As Blanning pro…

Review of Consciousness and Society by H. Stuart Hughes

This book is about a moment of transition in the 1890s, when philosophy and the social sciences decisively diverged. It is intellectual history at its best, combining biography, political issues, and how they impacted the theories that were struggling to emerge. A generation steeped in Enlightenment optimism and the peace of the Belle Époque, they beli…

Review of The Dawn of Everything by Graeber & Wengrow

Traditionally, scholars of “human nature” have focused on 2 opposing poles. Rousseau portrayed hunter-gatherers as existing in a state of childlike innocence, intellectually inferior but peaceful and without hierarchy. In his narrative, the agricultural revolution ruined this egalitarian paradise, introducing social class, inequality, and debilitating n…