Enlightenment mind, Christian sensibility

Review of Wollstonecraft: Philosophy, Passion and Politics by Sylvana Tomaselli

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-97) was one of the most famous writers of her time. As the author of A Vindication of the Rights of Women, she was a key thinker in the late Enlightenment, a proto-feminist, and the mother of Mary Shelley. What distinguished her was that she developed a popular philosophy and political program from experience, far beyond book learning.

Wollstonecraft grew up in poverty, under the brutality of an alcoholic stepfather. Leaving home at an early age, she founded an independent school with her sister, which they operated for 5 years. Upon her sister’s premature death in childbirth, she was forced to become a governess to an aristocratic family in Ireland; while treated well by the family, she despised the emptiness and vanity of their aristocratic life and resolved to make a living as an independent writer. This led to a career in journalism, with a first stop as a direct observer of the French Revolution, right through the terror. When her lover left her with a child in tow, she hit a low point and attempted suicide twice, only to decamp once again to Scandinavia, where she made trenchant observations about the culture of poverty. Her final act was an apparently happy marriage to William Godwin. Ten days after giving birth to Mary, she died from puerperal fever, leaving many unfinished manuscripts, including a novel.

Tomaselli’s book concentrates on the development of Wollstonecraft’s thought. Her first major book was on education. As a fully independent woman in a time that still envisioned arranged marriages as the ideal, Wollstonecraft was a revolutionary. In Vindication, she advocated not only for equality of the sexes in talent and ability, but that through public education, women should be enabled to live independently with full rights of citizenship. Marriage was an option, but should not be a necessity and certainly was not the best course for many individuals. Moreover, she abhorred the popular practice of arranged marriages for economic security, which led to widespread alienation, closing avenues of personal development, not to forget loneliness and individual unhappiness. It is a classic argument first articulated by Wollstonecraft.

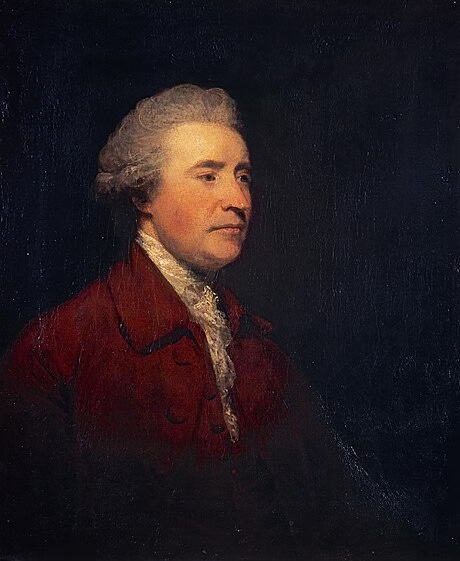

Setting herself against Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France, her time in Paris led her to explore deeper philosophical themes. Burke is a kind of lodestar nemesis throughout the entire book, her most fruitful philosophical foil. As Tomaselli emphasizes, Wollstonecraft found Burke extremely irritating, indeed much of her writing brims with rage.

On the one hand, she argued, there was the political liberation of the masses. The aristocratic order, with its presumed privileges and superiority, was decadent and should be swept away or at least fundamentally altered. Not only would it open society to great talent, she reasoned, but it would lead to a deeper kind of spiritual redemption. According to Wollstonecraft, Aristocrats existed in a narcissistic bubble, in which appearance mattered far more than what was inside. This warped their minds and their family life, encouraged infidelity and sensual dissipation, and was detrimental to society.

On the other hand, in alignment with the Enlightenment philosophes, Wollstonecraft strongly believed that the French Revolution was a major step that would lead to the betterment, if not some future perfection, of man. This is where her Christian sensibility – the naïve backdrop to many Enlightenment certainties – comes to the fore. In this view, human nature is essentially good, God set up everything with a purpose in mind (suffering was an opportunity for self-improvement in his plan), there are right answers that can be found through rational inquiry, etc.; the old order, and even institutional religion, was holding us back. With education available to all and the legal right of full participation in society, humankind would be able to flower to an extent hitherto unknown. It is an inspiring and almost fully modern vision.

Wollstonecraft’s trip to Scandinavia, where she observed how rural poverty stunted lives, crystalized her critique of nascent capitalism. The division of labor, she felt, was destroying the dignity of work, reducing skilled labor to repetitive tasks that would numb the mind. Apparently unaware of the impact that productivity gains were beginning to have, she advocated for the preservation and development of the previous order, in which cottage industries conferred a greater “degree of control” to laborers. If this sounds a bit naïve today, it raised a number of issues that later led to socialism.

However, if progressive, Wollstonecraft’s arguments were solidly moderate: she supported the existence of private property so long as there was a more equitable distribution of resources than was possible under the old regime. Moreover, she believed in the ennobling quality of working for a living, which would enable humans to both live independently and develop personally, bettering their minds and character. This might be an insipid nostrum today, but in her time it represented a radical refutation of caste stereotypes and even the racism informing slave labor.

Wollstonecraft died too young for her to develop a coherent philosophy in a definitive masterwork, but as Tomaselli argues, she probably would have done. I see her as solidly in the Enlightenment tradition of reason as the method that would culminate in the discovery of absolute truth, the “right way” for humanity. At times, her faith sounds almost utopian: in becoming sincere, self-aware, and educated, we would build a better society in which talent can develop and flourish, in which economic and personal independence would be ubiquitous, and where the better in “human nature” would dominate. Her daughter, Mary Shelley, would go on to question many of these notions – she became one of the most famous Romantics, the author of Frankenstein.

Tomaselli’s book is a very interesting read. Her writing is elegant and sometimes culminates in wonderful sum ups. She writes, for example, “Wollstonecraft never let go of the central plank of her moral critique, that it was vanity and the craving for self-worth through the admiration in the gaze of others that was the root of all evil.” Unfortunately, the book could have been much better as a fuller life and times biography. Wollstonecraft lived in a volatile era and experienced much of it directly, indeed it shaped her mind. I would have wanted much more on the context in which she operated. While Tomaselli covers the development of her mind competently, it is often with an academic pedantry that is not fun to read, however worthy it is of study.