Doomed republic, then the dictatorship of Augustus

Review of The Roman Revolution by Ronald Syme

This book covers the period roughly from Marius to Tiberius, which saw the fall of the traditional oligarchic republic and its replacement by the despotic monarchy that Augustus designed. While it covers a great deal of politics, it also addresses issues related to the administration of the Empire.

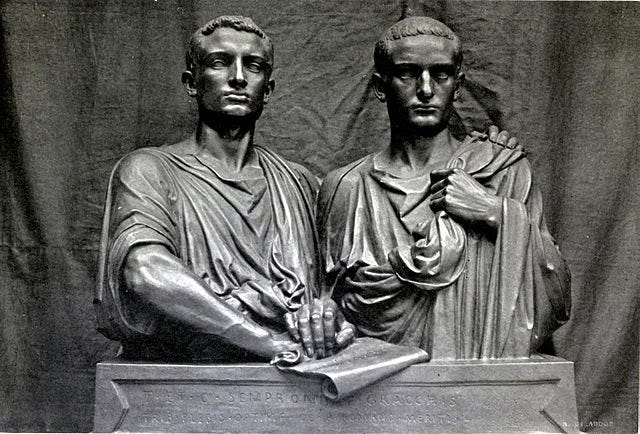

The empowerment of the Tribunes of the People under the Gracchi brothers (r. 133 and 122-121 BCE) created popular assemblies to make and veto law, originally the exclusive prerogative of the Roman Senate. While this enabled the Plebians to participate in power with the Patricians as near-equals, it also multiplied the opportunities for obstruction and delay. With the multiple new avenues to power, including mob-inciting demagogues who ruled the streets, a cacophony of laws were promulgated, though more often legislation was blocked by Tribunes. This created a dangerous political stalemate at a moment of fundamental change: the expansion of the empire beyond Italy. The army was gaining political power as enforcer and monopoly-holder of organized violence. For their part, the subject peoples became interested in accessing and influencing the old-style oligarchy.

Taken together, these developments pushed the Roman Republic into a period of unprecedented crisis. The result was over a century of recurring civil war, which almost invariably erupted during disputed transfers of power at the change of the yearly consulship. It was only Augustus (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE) who solved the question of who should wield power with the creation of a kind of monarchy, Symes concludes.

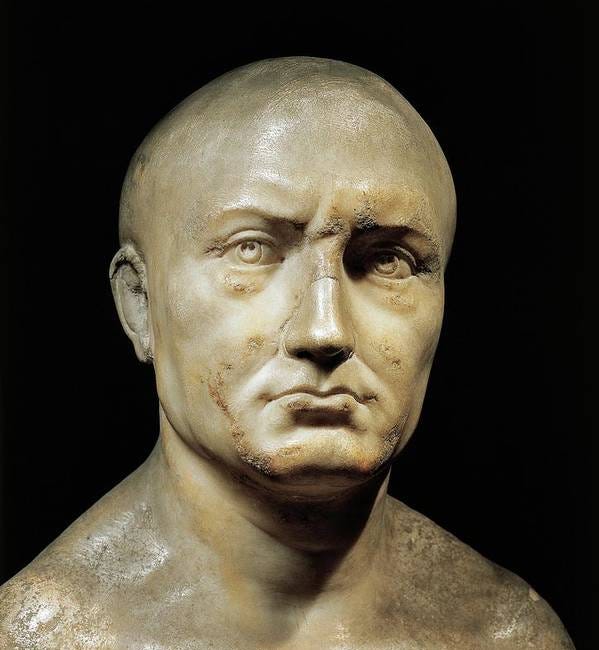

Prior to this prolonged crisis, Rome had been governed much as an imperial Greek City State, with a narrow local elite taking advantage of its subject peoples in support of their power games; responsibilities were thrust onto governors (for periods too short to learn much about their provinces) who usually had little knowledge of administration and usually cared nothing for the welfare of local subjects beyond the extraction of their wealth. The Roman Oligarchy had ruled for hundreds of years in this way in Italy, transferring power on a yearly basis to consuls as voted by the Senate, which prevented the development of entrenched, autocratic strong men. It was essentially an aristocracy of Patricians (descendants of those who overthrew the monarchy in 509 BCE) and rich Plebians who had achieved military glory in times of crisis (e.g., the Scipios, who defeated Hannibal in 202 BCE).

Senators had to maintain their prestige through lavish displays of wealth in public events but also to provide services to their client base, all to serve the glory of their families. Rather than parties or ideology, their power was based on family alliances as extended by a loyal "clientele" sworn to mutual assistance. Underneath them were the equestrians, who were businessmen and local aristocrats in the provinces; they concentrated on making money more often than sought glory. Finally, there was the proletariat. Only rarely did "new men", such as the military genius Caius Marius, arise to hold power in times of external threat.

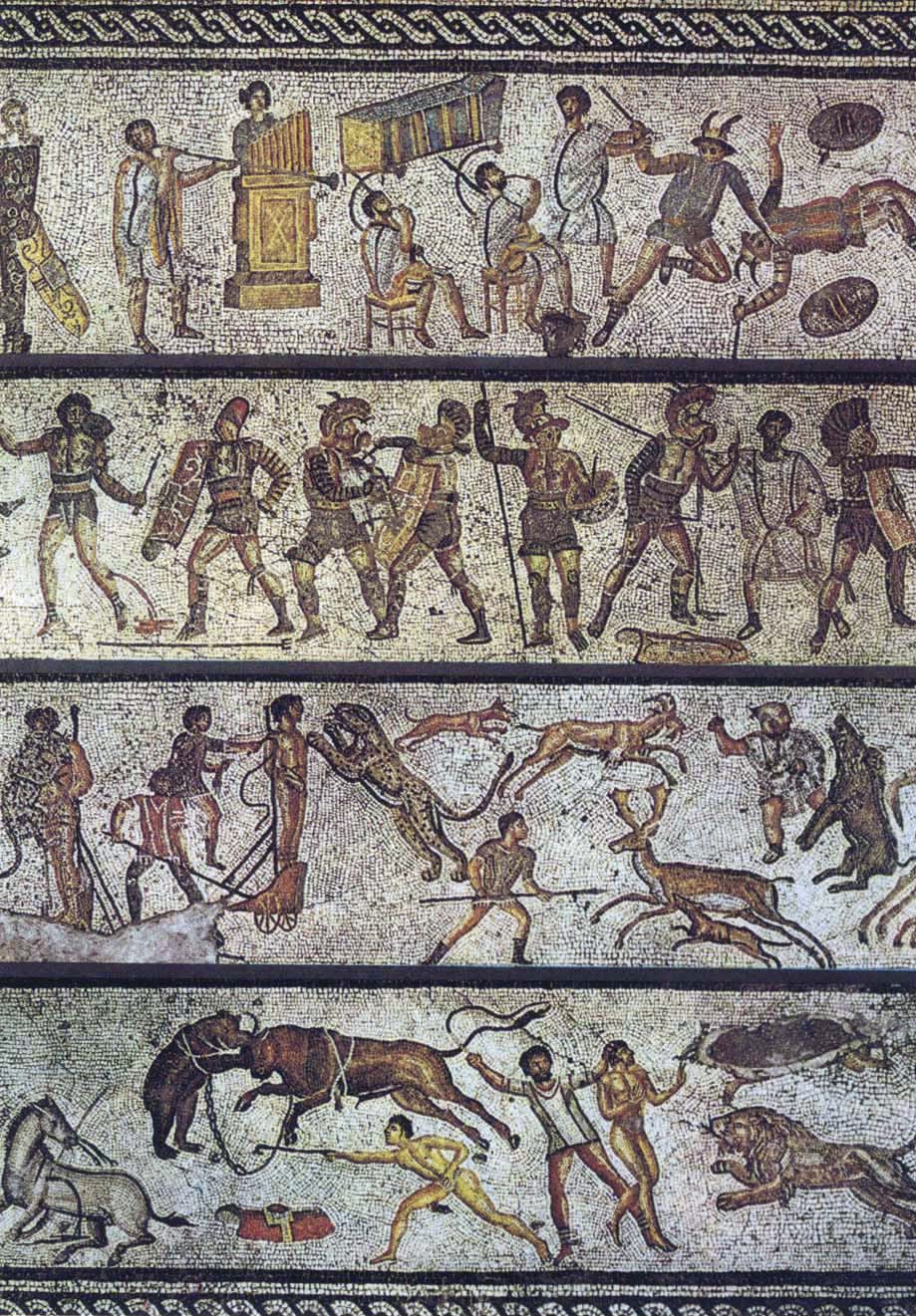

Politically, this system worked reasonably well until Rome became a Mediterranean superpower. Most important, the source of soldiers – gentleman farmers – proved inadequate to the requirements of years of foreign military service: they were too few and, in any event, they had to work the fields regularly or face ruin. This opened the way to the establishment of a professional army by Marius in 107 BCE, in which the proletariat and anyone else could serve for wages and make a career.

In addition, the subject peoples of Rome wanted the same rights as the citizens; they rebelled violently and had to be suppressed with increasing frequency. With the opportunities that the Tribunate offered to go over the heads of the Senatorial oligarchy, Marius had created a new structure of power in the professional army, which included both his loyal soldiers and the proletariat as well as the provincials - their loyalty began to go to the generals under whom they served rather than the quasi-religious fealty that the Republic and its Senate had enjoyed with the gentleman farmers.

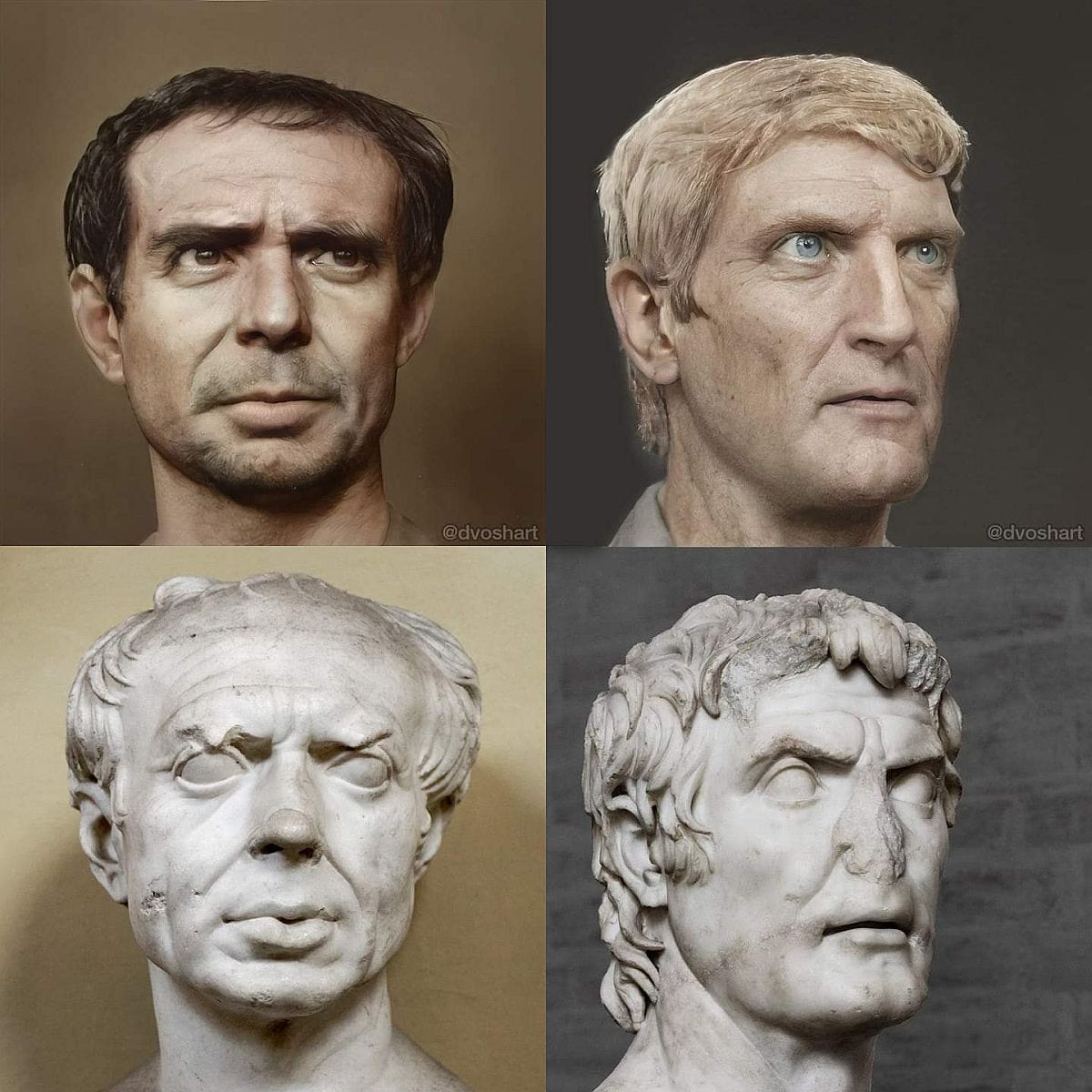

Sulla, Marius' protégé and then rival for power, attempted to reinstall the old oligarchy in an unprecedentedly bloody civil war (83-81 BCE) that wiped out a vast array of political talent from the ranks of the oligarchy and equestrians. It was here that the powerful generals – Pompey (allied with provincials) and soon Julius Caesar (a Patrician favoring the "common man") – emerged to battle the old oligarchy in a conflict that that culminated in the destruction of the Republic in 27 BCE.

While still a teenager, Octavian (mysteriously adopted by Caesar just prior to his assassination and later known as Octavius and then Augustus) then stepped into the breach. After much struggle that ended in civil war against Marc Antony, he completely reshaped the power structure. The true genius of Augustus, according to Syme, is that he was able to use the power of the armies north of Rome – he gained command of the most important nearby legions in case of need.

In addition, Augustus successfully channeled the ambitions of citizens into service to Rome (and to himself, of course). He did this by creating legitimate outlets for the energies of ambitious men of talent (as military officials but also as professional administrators), who served the state and empire as bureaucrats rather than constantly maneuvering for executive power within the traditional oligarchy.

Essentially, in addition to opening administration to talent from the provinces, Augustus made a major step in the establishment of the apparatus for a more modern state, replacing the amateurish and exploitive behavior of non-professionals that was the hallmark of Greek City States.

This is a wonderful interpretation that makes many aspects of Roman history comprehensible beyond naked grabs for personal power and glory. In Syme's view, the huge Roman Empire had become ungovernable by the fractious oligarchy, denuded as it was of talent over the previous 100 years of civil war. Augustus buried the old oligarchy while maintaining the appearance of the republic's institutions, bringing order at the price of liberty, which an exhausted citizenry apparently welcomed. It was truly the passing of a torch from a moribund, then decimated oligarchy to a new generation. The Roman state became more open to talent. There were plenty of aristocrats and wealthy notables who remained power players, but their influence was no longer guaranteed or exclusive. There is no doubt that much of this is accurate, in my opinion.

That being said, Syme makes many judgments that I found questionable, though they are of nuance rather than the core ideas regarding political power that I find very sound. He portrays Augustus as a proto-totalitarian, while I think he was a simple despot. He likes both Marc Antony and Tiberius, while I think they were mediocre libertines. These are things we can never know for certain, of course, so my interpretation is personal.

Regarding Syme's method, I want to add a note of caution for the reader. He assumes a certain level of knowledge; if the reader lacks it, the book will be very rough going and dry. You need to know not only who Sulla and Cato were, but also Livius Drusus, Crassus, the Metelli, and many, many others. Syme did not intend to retell any of the stories attached to them. You also need to know the history and chronology of Rome from about 150 BCE to 30 CE. If you have this grounding, the book is truly a joy of subtle interpretation and analysis accomplished by a master scholar, who knows every obscure scrap of written sources that supports his case. The book also has a quirky, though elegant writing style.

This is one of the best books on Roman history that I have ever read, but it is not for casual readers. You need to be something of a Roman history enthusiast before you read this, either at the undergraduate level or having read the wonderful historical novels of Colleen McCullough.

Related:

The role model for autocratic monarchy

Goldsworthy is, I think, the best living writer on Rome. His books, which are at once a pleasure to read as well as at the cutting edge of current scholarship, never disappoint. In this book, he takes on the man who completed what Julius Caesar, his great uncle and adoptive father, might have had in mind (or might not have). When compared to Julius, Aug…

The most famous Roman

Goldsworthy’s biography covers all of the things that Caesar did, from his political career to his military exploits. It is dense and fascinating, bringing to life a time but also the exceptional career of a leader from the Roman period that first offered a rich assortment of literary sources, along with ample archeological evidence.

Rome, Israel, and the early Christians

Starting from the reign of the Julio-Claudians (27 BCE to 68 CE), the book compares the cultures when the vassalage of "Judea" functioned well, follows the deterioration of relations that culminated in the destruction of Jerusalem (70 CE), and then examines the aftermath of repeated rebellions and the rise of Christians (and anti-Semitism). For many rea…

Case studies in Roman military leadership

In this book, Goldsworthy seeks to answer the questions, why did some Roman generals succeed outstandingly and what lessons we can draw? To answer them, he looks at a series of generals from the Punic Wars (3rd century BCE), which ensured Rome's survival and determined its future course, to the last great general, Belisarius, who tried and failed to rec…

Can you compare to ‘The storm before the storm?’ This was excellent and led nicely to Goldsworthy’s books.